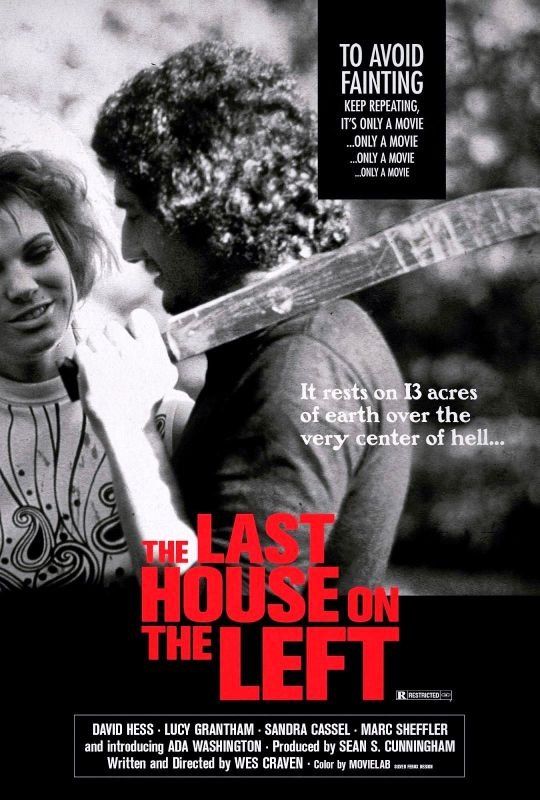

Frightmaster Wes Craven’s Legendary Career Got Off to a Famously raw Start and Closed With an Exceedingly Slick Finish with Last House on the Left and Scream 4 Respectively

Wes Craven’s 1971 debut Last House on the Left kicked off the late frightmaster’s career on an auspicious note. It is rightly considered a gritty, powerful and viscerally disturbing exercise in pure terror yet it is nevertheless chockablock with elements that aren’t just off: they’re egregiously, even surreally wrong.

It’s as if Craven filmed several completely different films at once. The first film is a wacky romp about a wealthy family dealing with the sexual revolution and counterculture in the form of her empowered daughter. The next is a gritty cautionary tale about a pair of nice young girls who make the wrong connections in the scary big city that is inexplicably wedded to a lowbrow country comedy about some seriously stupid law enforcement agents and their goofball misadventures. The final film is a wildly implausible yet effective revenge thriller.

Tonally, Last House on the Left is a mess. Much of the blame belongs to a glaringly incongruous bluegrass-inflected score that would be more suitable for a b-movie called Hillbilly Goofs & Moonshine Maniacs than it would be for a horror film so real and raw that it sometimes recalls snuff films, grind house thrillers and even home movies. Directing is largely a matter of making the right choices, and giving the film a lighthearted, even goofy score in the early going is a jarringly strange choice.

The film starts as a broad, almost homemade cinematic sitcom about an upper-middle class bourgeoisie couple, a doctor and his lovely wife, dealing with their headstrong, beautiful free-spirited hippie daughter and her desire to flee the suffocating safety and security of home and head to the city for a rock and roll show, some marijuana and maybe a little male companionship along the way

The tone is sitcom-broad to the point where a laugh track wouldn’t feel out of place. The folks are protective but supportive, and while they’d rather their beloved daughter didn’t venture into the city to rock out to a vaguely satanic rock and roll combo, they understand that an important, healthy component of growing up involves testing boundaries.

So after much frolicking, hippie-style, in green, lush areas, the daughter and her hard-partying friend head to the city in search of good times and also a little herb, a little greenery, and also some marijuana. So, really, on some level, Last House on the Left is a harrowing cautionary warning of what happens when nice young people do not have a solid, dependable weed connection.

In the city, the young people encounters some of the evilest lunatics ever to grace a film screen. They make the mistake of attracting the attention of kill-crazy fiends whose sins involve killing dogs, murdering Catholic clergy, both male and female, heroin addiction and the leader getting his own son addicted to smack. They are some nasty characters whose ranks include a wild young woman who is described repeatedly as looking like an animal, which is a 1971, b-movie way of saying both that she’s feral and also that she’s into women sexually.

These Grade-A creeps are like the Manson family minus the organization. They’re almost a caricature of what respectable folks imagined the counterculture was like. They’re out of their minds on drugs, transgressively sexual and a grotesque, gothic caricature of nuclear families. They are the worst humanity has to offer, and they are on a deadly collision course with some pleasant young woman only out for a good time.

In other words, they are the last people a pair of nice young women want to run into and, this being an early slasher film, they pay a horrible, disproportionate price for wanting to smoke pot and hang out in the big city and listen to pummeling heavy-metal riffs. They are tortured, sexually assaulted, tormented and then ultimately killed not far from the house where the daughter lives.

The raw power of Last House on the Left lies in its artlessness, in the sense that the footage we’re watching could just as easily have been shot by the murderers themselves, as a sort of cinematic trophy of their sadistic massacre. And while the performances and writing are not subtle, even at this early stage Craven had a real knack for creating memorable characters.

Accordingly, the most compelling and multi-dimensional figure in the movie is the heroin-addicted son of the lead creep, a tormented man-child controlled by his father through drugs yet a man who has a moral compass completely absent in his more sadistic and less conflicted peers. One of the girls tries to appeal to his sensitive side by nicknaming him Willow, in keeping with the film’s almost Terrence Malick-like deification of nature and wilderness, particularly when compared to the corruption and evil of man and his infinite perversions.

Eventually the creeps end up in the home of one of the girls they just killed. At this point the film takes another sharp turn when the parents, who we previously knew as a cutesy, adorably domesticated pair quickly discover that their visitors are not at all what they profess to be (a married couple working in “insurance” or something) and are actually the monsters who tortured, sexually assaulted and killed their daughter.

They then morph from corny mom and dad to cold-blooded killers who lure their daughter’s killers into deadly traps where they enact ferocious bloody revenge by doing things like biting off a man’s penis during oral sex and attacking a killer with a chainsaw. You know, real mom and dad stuff. The nice couple turns out to be even deadlier than the deranged killers, but their violence and bloodshed is righteous and merited. Or is it? Last House on the Left is single-mindedly devoted to scaring the bejesus out of audiences but it was also interested in exploring how the lust for revenge can corrupt even moral people, rendering them just as violent and rage-filled as the monsters in the midst.

Last House on the Left is sometimes distractingly weird and off. It’s hard to imagine another horror classic that would take the time for a comedy bit involving a pair of dopey cops trying to convince a sassy old black lady to let them catch a lift on a truck she’s driving that’s filled with chickens. The comedy in the film never works yet it somehow does not keep Last House on the Left from feeling disturbingly, disconcertingly real when it counts. It’s difficult to watch in the best possible way and paved the way for one of the most impressive horror careers of the past half century. Craven’s subsequent films would, by definition, be slicker and more professional but nothing he did afterwards quite matched the intensity of his debut.

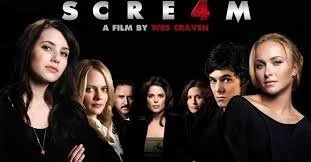

Sure enough, by the time 2011’s Scream 4 rolled around, Craven wasn’t a hungry, ambitious filmmaker so much as he was a lucrative brand, a name so commercial it was even slapped on low-rent projects Craven had little to do with, like Wishmaster. And the rough edges that defined Last House on the Left was replaced by a blinding commercial sheen befitting the fourth entry in a hit film series that, unlike Nightmare on Elm Street, found Craven in the director’s seat from the first entry to the last. At least until he died of course. Then he had no choice but to posthumously pass the torch.

Like 1994’s New Nightmare, Scream 4 found Craven returning to an iconic horror franchise after around a decade away. But where Craven returned to the Nightmare On Elm Street series because he had strong, audacious ideas he wanted to implement, he seems to have returned to Scream for the first time since 2000’s little-loved Scream 3 out of a strong desire for the big paychecks that accompany this type of gig.

Scream 4 is in many ways a victim of the franchise’s success. The post-modern elements that were once so fresh and clever long ago devolved into a glib, self-conscious gimmick. The Scream series itself played a huge role in making meta-horror just as tiresome as the non-ironic, unselfconscious variety but it had an awful lot of help from lesser knock-offs like Urban Legend.

Since Scream 4 is even more meta than previous elements. Its bloated, nearly two hour running time includes a good fifteen minute or so of characters discussing the film’s action, and the film-within-a-film’s action (that would be the Stab series, which the film establishes were based on the real-life doings documented in Scream and its sequels) in ways that make it achingly clear that they could just as easily be talking about Scream 4.

The film has a burning need to justify its existence so it tries to one-up earlier installments of the series in ways that only underline the filmmaker’s desperation. The Drew Barrymore opening to Scream was instantly iconic and established a template for sequels to follow but Scream 4 tries, and fails, to improve on a classic by having the first onscreen killing be revealed as a fake-out that’s actually happening in a Stab movie, not in what the young people probably don’t still call IRL.

Then Kristen Bell and Anna Paquin join the list of famous faces contributing cameos to the franchise in yet another fake-out once again revealed to be yet another scene from a goddamned Stab sequel. By the time we get around to the actual kick-off murder, the one that actually has something to do with what follows, I was already feeling exhausted by the film’s faux-cleverness, and it had barely begun.

Emma Roberts, Eric’s slightly more winsome and appealing daughter, stars as Jill, the cousin of Scream heroine Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell). As the film opens, Sidney is returning to her hometown to promote a book about her experiences with demented slasher Ghostface. Meanwhile, a whole new generation of high school kids obsessed both with the real-life murders that made Sidney famous and the hit slasher series they inspired prepare for a marathon of Stab movies that goes murderously awry.

Bodies begin to pile up and returning faces Dewey Riley (David Arquette) and his frustrated journalist/author wife Gale Weathers-Riley (Courtney Cox) once again find themselves on the trail of a masked slasher way too into horror movies, and also into perpetrating actual real-life horror. Scream 4 introduces some potentially provocative ideas about the new killer wanting to further blur the lines between horror entertainment and real-life bloodshed by making a homemade snuff film out of their crimes and the Stab franchise being a crazy funhouse-mirror version of the town’s tortured history but mostly Scream 4 just feels exhausted and arbitrary.

In many ways, the film is the antithesis of Last House on the Left, a movie that is referenced more than once. Where Last House on the Left’s power lie in its raw, brutal, almost amateurish intensity, Scream 4 is slick and professional to a fault. Where Last House on the Left is all over the places tonally, a bizarre mixture of tones and genres that shouldn’t work anywhere near as well as they do, Scream 4 maintains the same glib, darkly comic and cynical tone from the first frame to the last.

Like its predecessors, Scream 4 is part blood-splattered mystery full of red herrings and potential killers, part coldly efficient slasher film and part meditation on the conventions of the genre. Scream 4 makes sure to update the proceedings with cell phones and texting and computers and lots of talk about the plague of lazy horror remakes of classic movies (a trend that includes, of course, Last House on the Left, The Hills Have Eyes and Nightmare On Elm Street, all of which had been remade at that point) but the series seems to be operating on auto-pilot.

As a filmmaker, Craven was generally interested in more than scares, more than shock and more than primal horror but Scream 4 is distressingly empty and vacuous, a film whose only reason to exist, beyond commercial considerations, lie in its vastly over-estimated sense of its own cleverness. Scream 4 is far from the worst film in Craven’s career, as he made some real stinkers, but it is perhaps his least essential. Craven enjoyed one of the greatest careers in cinematic horror but where his first film was a touchstone of the genre, he ended his career with a slick mediocrity that’s little more than a footnote to both Craven’s filmography and a series that single-handedly reinvented horror the first time around but had run out of steam when Scream 4 anti-climactically brought it back to lurching, flailing life fifteen years later.

Pre-order The Fractured Mirror, the Happy Place’s next book, a 600 page magnum opus about American films about American films illustrated by the great Felipe Sobreiro over at https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!