Stanley Kubrick Was Born 96 Years Ago Today. I'm Honoring that Milestone by Rerunning This Piece on How Eyes Wide Shut Fucking Sucks

Room 237, the riveting cult documentary on various theories behind the making and meaning of The Shining, indelibly conveys the surreal depths of our reverence for the intelligence and artistry of Stanley Kubrick.

The obsessive theorists interviewed in the film assume that Kubrick had to be going for something more in the making of The Shining than merely creating one of the most terrifying and unforgettable horror movies ever and adapting a novel by one of the most popular and influential writers of the past century.

For these true believers, creating pure terror that would be remembered, spoofed, and ripped off for decades was merely the first, most obvious level Kubrick was operating on. More importantly, according to these eccentrics, at least, he was furtively confessing to having staged the moon landing or mourning our country's treatment of Native Americans or various other fascinating, crazy theories that could be true but almost assuredly are not.

This theorizing captures how fans see Kubrick not just as an exceptional talent but rather as something close to magical, a genius operating on so many levels that we mere mortals can barely even comprehend them. But before he became one of cinema's uncontested Gods, Kubrick was merely a talented, intense young photographer looking to break into the film business.

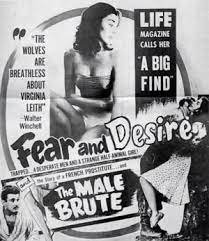

Kubrick made his debut with the micro-budgeted anti-war message movie Fear and Desire, but the film went unseen for decades while its director ascended to astonishing heights. Kubrick himself was not a fan of the film, seeing it as a juvenile embarrassment best left permanently lost, but the film was eventually found and restored. In 2012 it was released on DVD and Blu-ray so a mass audience that worships Kubrick could finally find out for themselves whether the film was as unreleasable as its director insisted.

Kubrick’s embarrassment over his debut might be attributable to the way that it broadcasts its ambitions and its seriousness in a very “serious young man on the go” kind of way. The movie feels like a debut novel in that respect, but one from a talented author with a pretty clear sense of who they are and what they want to do.

Fear and Desire begins with portentous narration informing us that what we are watching is not the story of one specific war and one specific group of soldiers/combatants, but rather a story representative of all soldiers and all wars. The movie follows what sure appears to be a quartet of American soldiers who venture behind enemy lines and must find a way to get back to the front.

Frank Silvera, who has the kind of face that would allow him to play a Dick Tracy villain without make-up, plays a working-class sergeant named Mac (obviously) who seizes upon the idea of killing an enemy general as both an important military objective and a way to redeem an existence otherwise devoid of accomplishment or distinction.

Kenneth Harp plays the challenging dual role of Lt. Corby, an inveterate leader and wordsmith who takes charge in a crisis as well as an enemy general similarly prone to philosophizing darkly about the nature of war and death. Steve Coit plays a less challenging dual role as the least distinctive soldier and the opposing general’s associate, while future filmmaker Paul Mazursky gets the juiciest role as Sidney, a soldier afflicted with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder who begins the film a little off and grows progressively more unhinged.

I know of Mazursky primarily as a pot-bellied director and character actor. So it’s jarring and distracting to see him not just play a challenging, fairly central role in a Stanley Kubrick movie but to throw himself into the Marlon Brando method acting Olympics with a delirious fervor that should be embarrassing but is instead surprisingly compelling.

Mazursky doesn’t just act here; he ACTS. Every moment in the film belongs in his actor’s reel. Even at the embryonic beginning of his career, Kubrick had a photographer’s inveterate fascination with faces and composition. Mazursky never looked younger or more heartbreakingly boyish than he does here.

The actors play tried-and-true war movie archetypes they’re able to elevate into real characters with real depth and pathos. Mazursky is “The Kid” and “The Kook” as well as a warped romantic whose understandable carnal desire for a beautiful enemy civilian woman (played by Virginia Leith), the soldiers find and take hostage leads to tragedy for them both.

It’s hard to overstate the “Marlon Brando on Mescaline” bigness and theatricality of Mazursky’s performance, which entails silent-movie style clowning, liberal interjections of Shakespeare, visceral romantic yearning, insanity, and killing. Mazursky’s performance is effective in part because Leith exudes such convincing terror.

Leith is all the more effective for not having any dialogue. She is fear incarnate, and Fear and Desire intriguingly invites us to identify with this wordless hostage as much as it does the quartet of soldiers at its core. An air of sexual menace hangs heavy over the scenes involving the soldiers and their gorgeous, terrified hostage. When the soldiers are trying to decide what to do with her, “sexual assault” appears to be an unspoken but horrifyingly real possibility.

Fear and Desire feels weirdly like an early, lost film of Terence Malick rather than an equally enigmatic, reclusive cinematic master in no small part because, as in The Thin Red Line, the soldiers here think like philosophers and talk like poets. The movie is similarly obsessed with war as a violation of nature, but where Malick would take hours of ennui to tell a story like this, Kubrick wraps it up succinctly and hauntingly in barely over an hour.

Kubrick didn’t just direct Fear and Desire. He also shot it, edited it, and produced it on a small budget with a tiny cast and crew. The master may have made Fear and Desire as a way of learning, on the job, how to make a movie, but being Stanley Kubrick, he made a dark, distinctive, and fascinating movie in the process.

By the time Eyes Wide Shut began one of the longest and most dramatic/public shoots of all time in 1996, Kubrick was firmly established as a cinematic God, and Eyes Wide Shut was, and remains, one of the most talked-about and controversial shoots and films of all time.

Kubrick’s return to filmmaking after a decade-plus absence alone made it a pop-culture event. Throw in a shoot that dragged on interminably, the most famous (and weirdest) movie-star couple in the leads (that would be Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, back in her Scientology days), and threats of an X-rating thanks to extensive nudity and sex, some of it during elaborate robed orgy scenes, and you have a movie of equal fascination to sleazy tabloids and cerebral film journals.

they have fun!

Eyes Wide Shut was one of the first big movies I reviewed as a professional film critic at The A.V. Club. In my early 20s, I couldn’t imagine Stanley Kubrick making a movie that was not great. Re-watching it for this column, I couldn’t imagine a scenario where I would like the movie. As a relative newcomer to the reviewing game, I don’t think I thought I was allowed to give Stanley Kubrick a bad review. But I also think I was genuinely blown away by the film, finding it to be a hypnotic and dream-like exploration of fantasy and desire and rage and sexual jealousy.

Re-watching it, however, just about everything struck me as wrong, beginning with Cruise’s bizarrely bad performance as Dr. Bill Harford. It’s a misbegotten star turn that oscillates between the hammy bigness of Cruise’s usual persona — the big hair, the ever-ready mega-watt smile, the rooster strut, the mannered creepiness — and a dead-eyed blankness whenever he’s called upon to look traumatized thinking about his wife’s torrid infidelity with a naval officer out of a cheap romance novel in black-and-white sequences that look like they could have been purloined from any number of Cinemax erotic thrillers from the 1990s.

Cruise was still in his mid-thirties when shooting began in late 1996, but because he’s so freakishly well-preserved, he barely looks old enough to drink legally and behaves less like a real doctor than a doctor Cruise might play in one of his cocky-young-man-crowd-pleasing dramas, like Top Gun or Days Of Thunder. Despite seeming like an alien doing only a semi-convincing impression of a human being, pretty much every woman in the film wants to have sex with Bill, offer themselves to him, or shoot him an inviting and flirtatious look. Yet Bill remains haunted by the image of his sexpot curator wife Alice (Nicole Kidman) having sex with the aforementioned handsome naval officer she fantasizes about sexually, something she shares with her jealousy-crazed husband and that sends him on a dark, treacherous sexual journey of discovery of his own.

Eyes Wide Shut can only really be understood as a fantasy, a waking dream, but even by those standards, it’s distractingly broad and fake. Early in the film, for example, Alice flirts outrageously with an international playboy who isn’t just a continental charmer but pretty much a human, live-action version of Pepe Le Pew.

Cruise is unconvincing as a doctor here, but he’s equally unconvincing as someone married to a woman played by Nicole Kidman. That’s weird, considering that Cruise and Kidman were married at the time. Everything about the movie feels almost as unconvincing. Kubrick was born and raised in the Bronx yet created a New York for the film that never feels like anything other than a terrible set on a soundstage in England because that’s exactly what it is. Eyes Wide Shut similarly features some of the least convincing stoned behavior in memory, no mean feat considering that stoned antics in movies are pretty much unconvincing and over-the-top by design and by default.

The film’s plot, at once threadbare and overwrought, finds a sexually frustrated Bill Harford stumbling upon a secret world of sex and debauchery involving nearly naked young women having sex with overly clothed, overly cloaked, and masked old men wearing ugly masks. An air of sexual violence hangs heavy over the debauchery, and when Bill’s unwelcome presence is detected, he embarks on a life-and-death journey to uncover the true nature of the orgy.

Eyes Wide Shut takes itself very seriously in a way that made me wish Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove Terry Southern was alive to rework the script and remind the old master that sex, in movies at least (which, it should be noted, is very different from sex in real life, particularly here) is weird and humanizing and funny, and not dour and soul-crushing and something that should be handled with the solemnity of a funeral dirge.

For a movie advertised as a touchstone for screen sexuality, Eyes Wide Shut is astonishingly un-sexy, and for a movie about freaky, quasi-satanic orgies, its version of kink is awfully old-white-man vanilla. Kubrick may have set out to make a movie that scandalized both audiences and his ultra-mainstream, mega-movie star leads. Instead, he made a movie about sex that’s smutty and dumb where it wants to be seductive and wise. It’s a vision of gothic debauchery whose greatest crime is that it’s unforgivably boring.

The kindest reading of Eyes Wide Shut may be that it somehow exists in the time-warped universe of The Shining and functions as a stealth spin-off/prequel featuring some of the debauched, evil, hell-bound hedonists whose bad vibes and evil lives contribute to the bad mojo over at The Overlook Hotel.

Eyes Wide Shut has some of the same creepy atmosphere as The Shining, some of its disconcerting, intentionally alienating otherworldliness. The big difference is that the restless intellects of Room 237 devised simultaneously outrageous and sort-of plausible theories in an attempt to discern the ultimate truth of The Shining, while I have to connect these two films in my mind and create a context for the film’s leaden tedium just to deny my overwhelming sense that I’d just watched the first (and, thankfully last) bad movie of one of our greatest filmmakers.

Nathan needs teeth that work, and his dental plan doesn't cover them, so he started a GoFundMe at https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-nathans-journey-to-dental-implants. Give if you can!

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here

AND you can buy my books, signed, from me, at the site’s shop here