Preston Sturges' Timeless Masterpiece Sullivan's Travels Is Wonderful and Wise

Like Network, Preston Sturges’ elegant 1941 Hollywood fable Sullivan’s Travels is blessed with eternal timeliness. Sturges’ deeply humane masterpiece will always be relevant to whatever we happen to be going through as a country and a culture but sometimes it’s more resonant than others. We unfortunately happen to be living, and suffering, through one of those eras.

Like John L. Sullivan, Sullivan’s Travels poignantly pampered protagonist, we live in perilous times, times of great division where we are continually assaulted with images reflecting the inexorable ugliness of contemporary American life: children torn apart from parents, never-ending spree killings that shake the soul and horrify the spirit and an increasingly ugly culture war that brings out the worst in everyone, particularly on social media.

Contemporary filmmakers face the same vexing dilemma Sullivan did: how do you best serve the public and your own demanding muse during periods of great division and uncertainty? Do you make “serious” films that address the ugly issues of our times head-on in an attempt to promote social change? Or do you double-down on escapism because the beaten-down masses need escape and distraction in trying times, not to be perpetually reminded of their sorrowful lot in life?

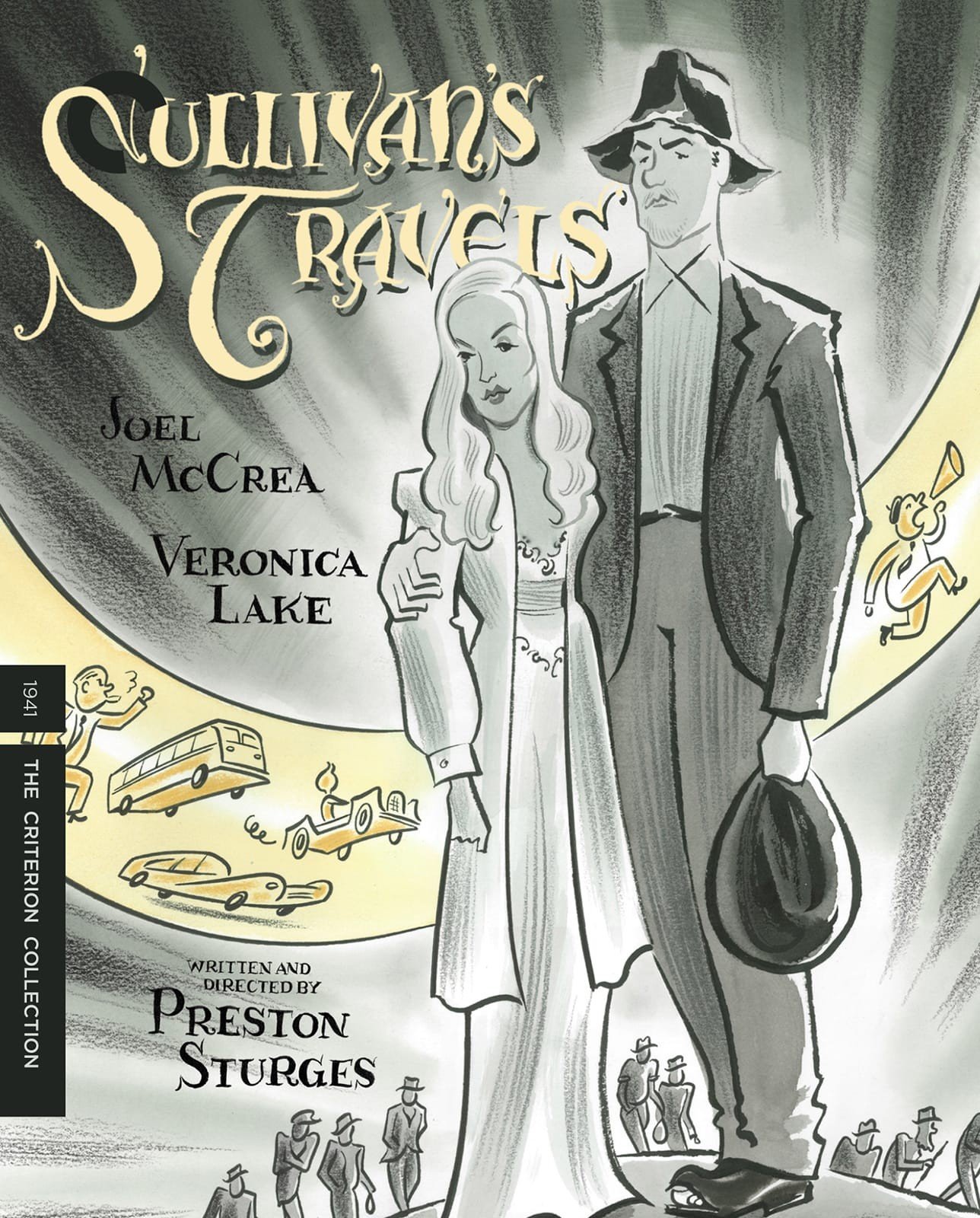

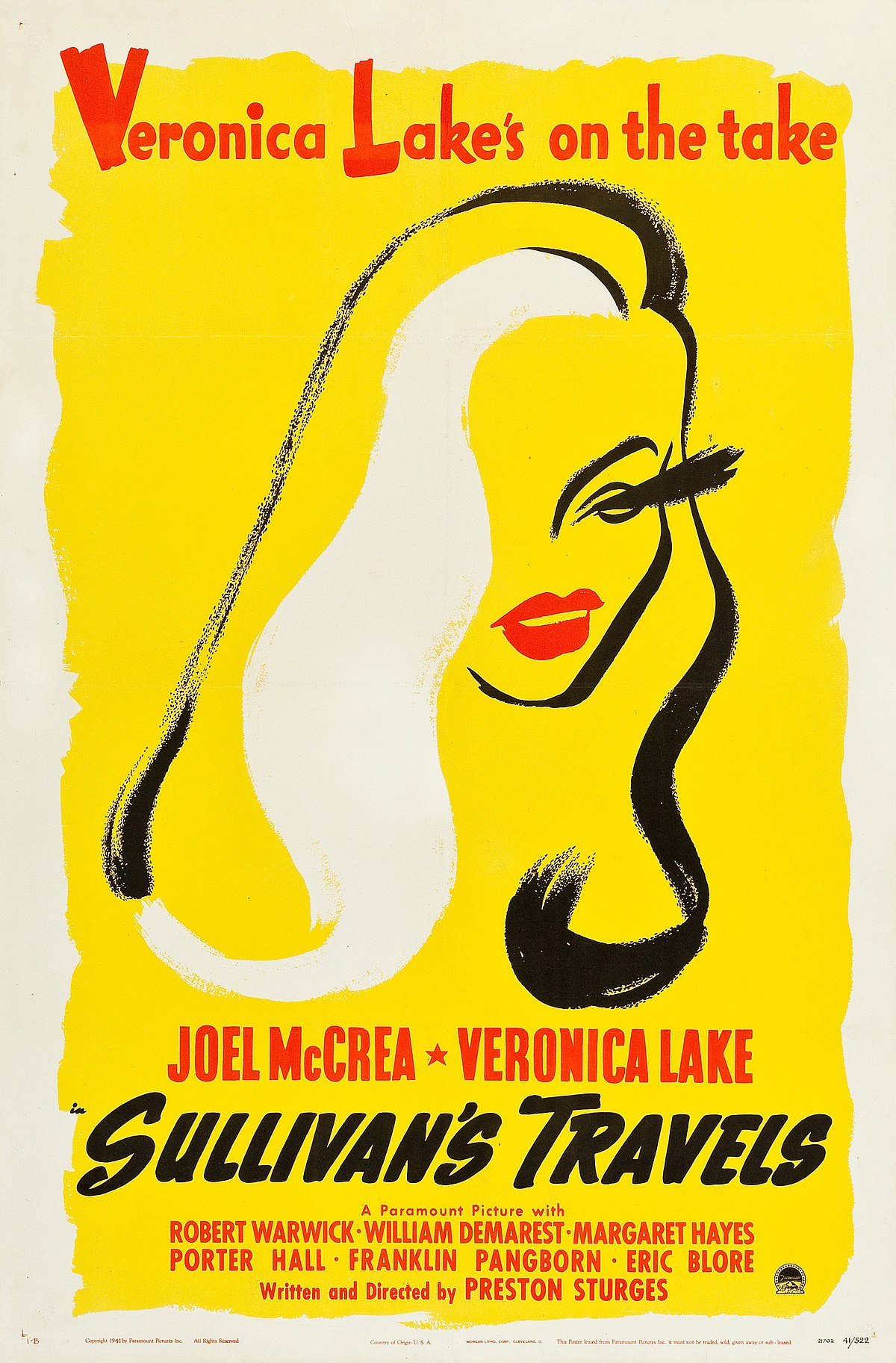

Our idealistic, adorably myopic hero, played with gruff, apoplectic intensity by the great Joel McCrea begins Sullivan’s Travels under the delusion that it is not just his job but his sacred moral obligation to make a somber exercise in gloomy social realism called O Brother, Where Art Thou? The confused filmmaker learns, through brutal firsthand experience that he’s better off providing distraction and escape to a populace that desperately needs it.

Sullivan opens the film burning with the kind of good intentions that invariably lead straight to hell. He’s sick of making idiotic comedies for the masses like So Long, Sarong, Hey Hey in The Hayloft and Ants in Your Pants of 1939. He’s tired of prostituting his gift for his studio masters and wants to make a “commentary on the human condition,” a film chockablock with “stark realism” that would, in Sullivan’s wildly hyperbolic turn of phrase, “realize the potentialities of film as the sociological and artistic medium that it is.”

Sullivan’s bosses are understandably wary, but they seem open to their star entertainer venturing scarily into the world of art and social commentary on the basis that, in addition to the aforementioned stark realism and commentary on the human condition, Sullivan’s next film also contain “a little sex” as well.

In other words, Sullivan is intent on making the kind of movie that no one would actually watch, let alone enjoy, but his corporate masters, one of whom sports a distracting resemblance to Walt Disney, the hero of the film’s rightfully revered climax, can’t talk sense into him. Sullivan doesn’t just want to make the kind of depressing exploration of poverty and despair that inevitably proves box-office poison; he wants to experience that poverty and despair firsthand so that he can tell the story of our country’s forgotten man from a place of realism, experience and authenticity.

So our hero decides that in order to truly articulate the innate dignity of the suffering masses he’ll need to go undercover as someone at the very bottom of the socioeconomic ladder, namely, the mighty American hobo.

To Sullivan, poverty and desperation is an outfit he can put on and discard as cavalierly and nonchalantly as a Halloween costume; for the genuinely poor, however, it’s something closer to a grim, unchangeable fate, a bleak destiny. It’s a luxury of the rich and famous to be able to promenade as the desperately poor and then return to their lives of privilege when that wears out its welcome or purpose. The poor, alas, do not have that option.

Sullivan keeps trying to leave his pampered life in Hollywood and become one of the unwatched wretches he plans to make a movie about but for a solid hour all roads lead back to Hollywood. Sullivan seemingly cannot escape his fate. Privilege and comfort quite literally follow him wherever he goes in the form of a souped-up RV from the studio so overflowing with amenities that it’s essentially a mansion on wheels. The RV and the many, many people inside it are supposed to save Sullivan from himself, to keep him on a leash, as it were, but Sullivan eventually manages to evade the people paid handsomely to keep him from danger.

In the course of his maddeningly circular journeys, the slumming Hollywood big shot meets Veronica Lake as The Girl, a tart-tongued actress and razor-sharp wit who has just about given up on Hollywood and its lecherous producers and directors when she meets a famous filmmaker in the midst of a social experiment that’s about to play out in ways the filmmaker could not have anticipated.

this is Quentin Tarantino’s favorite shot

There is a musicality to Sturges’ dialogue here, a beguiling rhythm, a staccato, percussive stomp. In its early going, Sullivan’s Travels is a sublime comic symphony executed by a cast uniquely qualified to help Sturges realize his artistic vision.

Sturges loved words like few filmmakers before or since. His exquisite screenplays double as valentines to the English language. In Sullivan’s Travels the wisenheimers who occupy Sullivan’s Hollywood world talk for the pleasure of talking. They talk as if conversation is a sport and they’re all Olympian-level competitors. They talk to amuse themselves and each other but the hobos and prison-camp laborers that Sullivan encounters in his journey into misery don’t talk at all.

Life has beaten the conversation out of them. In Sturges and cinematographer John F. Seitz’s expert hands, the silence of the wretched poor becomes enormously powerful. It speaks eloquent volumes without a single word.

When Sullivan finally manages to escape the golden handcuffs of his Hollywood life as a big-time filmmaker for a hobo’s migratory, desperate existence, the film shifts tone dramatically from effervescent, intensely verbal comedy to a dour melodrama of human suffering on an almost biblical level.

For long stretches Sullivan’s Travels is silent. For a filmmaker as innately funny as Sturges, deliberately choosing to forego laughter is a bold choice that pays huge dividends. In Sullivan’s Travels Sturges puts tremendous faith in the power of images.

Sturges was a peerless curator of faces. His repertory company of brilliant character actors like William Demarest, Porter Hall, Charles R. Moore and Franklin Pangborn was full of wonderful faces, faces with character, faces with personality, the faces of people who have lived rich, full, complicated lives.

Sturges’ usual cast of characters is utilized to brilliant effect here but their faces are not quite as unforgettable as the mugs of the miserable poor, who similarly have wonderful faces full of personality and character that are also unmistakably the faces of people who have suffered and continue to suffer, whose lot in life is to suffer and then to die.

In its third act, something terrible happens to Sullivan: he gets what he wants. The universe punishes Sullivan for his hubris and his delusions when he ends up on a chain gang after a violent run-in with a railroad employee.

Sullivan’s Travels is never more heartbreaking or heartstrings-tugging than during the set-piece where the soul-deep misery and despair of Sullivan and his fellow convicts is momentarily alleviated when they get to watch a Disney cartoon at a black church that doesn’t just accept but embraces these troubled men with Christ-like selflessness. Beyond everything else, this sequence is a poignant fantasy of true, total integration of soul and spirit, where black and white, poor and middle-class put their differences aside for the sake of spiritual and cinematic communion.

Sullivan’s Travels’ style becomes impressionistic and subjective, mirroring the disorientation and confusion its hero is experiencing after he’s robbed and assaulted and assumed dead. For a classic comedy overflowing with laughter and quotable lines, Sullivan’s Travels is fundamentally a very serious, even somber film about very serious issues. It’s the perfect combination of O Brother, Where Art Thou? and Hey, Hey In The Hayloft, a laugh riot that’s also a powerful meditation on the nature and purpose of art and entertainment.

Within Sturges’ career, The Great Moment, his famously failed biopic of William T. G. Morton starring Joel McCrea, is considered his big dramatic detour but Sullivan’s Travels is every bit as dramatic as The Great Moment, if not more so. Both films combine comedy and drama; Sullivan’s Travels just does so in a much more satisfying, crowd-pleasing and successful fashion.

Sullivan’s Travels is affectionately dedicated to “the memory of those who made us laugh; the motley mountebanks, the clowns, the buffoons, in all times and in all nations, whose efforts have lightened our burden a little.” A great and silly, as well as ridiculous and wise, master filmmaker was paying homage to all of the mirth-makers that make a grim world a little less brutal.

We need those clowns and buffoons more than ever these days, as well as towering geniuses like Sturges, whose magnum opus couldn’t help but illuminate the complexities and drama of the human condition even as it made delicious comic sport of self-serious souls like its well-meaning but misguided hero, who take it upon themselves to create, in Sturges’ indelible turn of phrase, “a true canvas of the suffering of humanity” when they’re better off making people chuckle.

That’s the kooky magic of Sullivan’s Travels; it’s suspicious, if not downright contemptuous of pampered entertainers like Sullivan who feel the need to make grand social statements and engage in weighty social commentary, but it's also a veritable master class in how to use breezy, funny entertainment to make grand social statements and engage in pointed social commentary.

All with a little sex, of course.

Would you like an entire massive book FULL of articles like this? Check out the Kickstarter for The Happy Place’s next book, The Fractured Mirror: Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place’s Definitive Guide to American Movies About the Film Industry here: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/weirdaccordiontoal/the-fractured-mirror?ref=project_build

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only!

PLUS, for a limited time only, get a FREE copy of The Weird A-Coloring to Al when you buy any other book in the Happy Place store!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!