The Fractured Mirror 2.0 # 6 Directed by John Ford (1971)

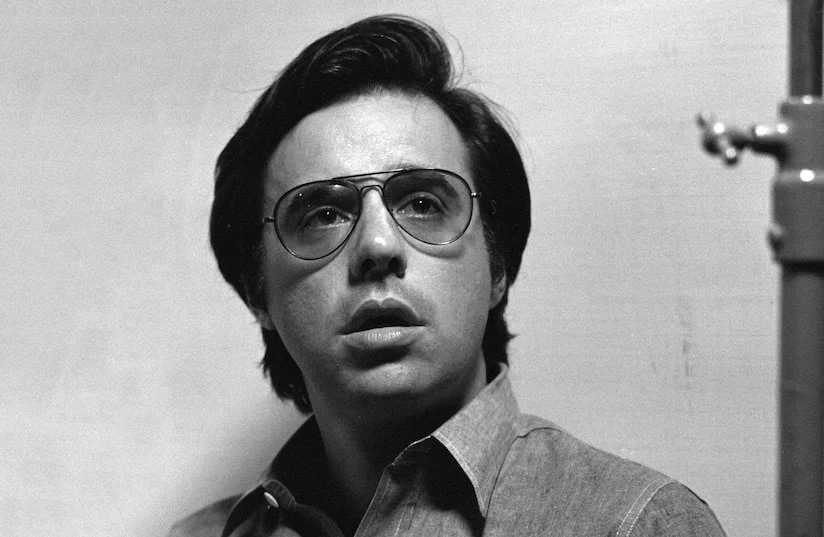

Raconteur, bon vivant and Olympics-level kibitzer Peter Bogdanovich was nearly as famous for talking about movies as he was for making them. Even in a New Hollywood filled with cinephiles for whom cinema was a religion as well as a business and an art form, Bogdanovich’s obsessive film geekdom stood out. In an exciting, dynamic realm full of die-hard film geeks, Bogdanovich was the geekiest.

In the late 1960s and 1970s Bogdanovich enjoyed a reputation as an “auteur whisperer” with a famously easy rapport with the likes of Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock. Bogdanovich approached the sacred art of film from seemingly all angles. He was a director first and foremost, of course, but also a screenwriter, an actor, a critic and film historian.

None of that seemed to have mattered to John Ford, however, when the famously cantankerous old man sat down with a cigar in his beloved Monument Valley to be interviewed by the hotshot young filmmaker for the fascinating, frustrating 1971 documentary Directed by John Ford.

Bogdanovich makes the mistake of asking the legendary filmmaker/grouch to either cosign or refute Bogdanovich’s own theories about his work. It instantly becomes apparent that Ford has zero interest in talking about film theory, as it relates to his own life’s work or anyone else’s.

The contentious first few interactions between Bogdanovich and one of his cinematic heroes resembles a cinephile version of the old Mad Magazine feature “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions.”

When Bogdanovich nervously asks Ford how he shot a particularly bravura sequence in 3 Bad Men he hilariously deadpans, “With a camera”, which is technically true but also deeply unhelpful.

When Bogdanovich asks Ford if he’s aware that his view of the West has grown increasingly melancholy over time, he snaps back, “No.” When asked to further elaborate on Bogdanovich’s idea, he counters, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

When Bogdanovich asks Ford what appeals to him about the western, the most legendary western filmmaker of all time demurs, “I wouldn’t know” and when Bogdanovich asks Ford, “Would you agree that the point of Fort Apache was that the tradition of the army was more important than one individual?” a palpably irritated Ford actually calls “cut” in a manner that’s half-joking at most.

Ford assumes total control of the interview from the very beginning. When “take one” is called, Ford grouchily insists, “Take one? There won’t be more than one take, will there?” This may be Bogdanovich’s movie but in these sequences, Ford is the one calling the shots.

In fascinating, revelatory and often bleakly funny interviews John Wayne, Henry Fonda and James Stewart talk about how Ford’s unusual and sometimes sadistic working methods involved singling out someone for abuse every day.

Ford seemed to need a daily scapegoat to focus his malevolent, chaotic energies upon. Since John Wayne worked with Ford more than anyone else, he consequently found himself unhappily occupying the role of the unfortunate soul singled out for directorial bullying more than anyone else.

To the rest of the world, Wayne might have been the rugged, imposing personification of American machismo but Wayne’s own words make it clear that Ford had all of the power in their longstanding, important working relationship and wasn’t afraid to use or abuse it.

We see a different side of Wayne in Directed by John Ford. He’s seldom, if ever, seemed more vulnerable or human than he is here talking about his love-hate relationship with his star-maker and how he was willing to accept being bullied in exchange for the opportunity to do the best work of his career. He’s not the only one who accepted a Faustian bargain: endure Ford’s cruelty and callousness as an acceptable cost for his singular genius.

When he sat down at the feet of a master to soak up his wisdom Bogdanovich unfortunately found himself in a position Wayne was all too familiar with: being the butt of Ford’s scorn and derision.

Elaine May couldn’t write comedy as excruciatingly awkward and uncomfortable as Bogdanovich’s first few exchanges with Ford. Depending on your tolerance for cringe comedy, it’s either a good thing or a bad thing that Bogdanovich’s decidedly one-sided conversations with Ford represents only a small part of the cinephile icon’s achingly sincere valentine to a filmmaker who, needless to say, did not reciprocate his love.

Bogdanovich seems to have talked to Ford just long enough to realize that there was nothing much to be gained talking to a man who seemed to hold the idea of self-reflection in vitriolic contempt.

When he’s not being nakedly contemptuous, Ford gives the kind of rudimentary answers you’d expect from a man of his time who apparently believed that the unexamined life was the only one worth living.

But if Ford is fascinatingly, hilariously uncommunicative, even pugilistic, in his stubborn unwillingness to give Bogdanovich what he wants the film’s other interview subjects more than make up for it both in candor and star-power.

Ford certainly lacks the homespun charm and gift of gab of Stewart, who refers to kissing up to the six time Academy Award winner as “red-appling the old man” and tells a great story about nearly making it through the filming of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence unscathed until Ford asked him what he thought of a costume the great black character actor Woody Strode was wearing for a specific scene.

When Stewart had the poor judgment to reply that it looked a little “Uncle Remus-y” Ford saw his opportunity to knock the beloved American icon down a peg and told the cast and crew that Stewart had a problem with Strode’s outfit, possibly attributable to his racism. This mortified Stewart and delighted Wayne, who was happy not to bear the brunt of Ford’s mean streak for once.

Ford worked with the same actors over and over again. Ford assembled an extraordinary repertory company that functioned as a makeshift family, albeit the kind where the adult children spend their lives in therapy in an attempt to deal with the verbal and emotional abuse they survived.

When it came to articulating the enduring greatness of John Ford in documentary form, the director of How Green Was My Valley and Grapes of Wrath was more of a hindrance than a help.

So Bogdanovich tells Ford’s story and makes an overwhelmingly successful case for his status as one of the all-time great American artists, not just filmmakers, not through Ford’s grouchy, almost perversely unedifying words but rather through the affectionate but honest recollections of his most important collaborators and an insanely generous collection of clips from Ford’s rightly storied career.

Bogdanovich is not know for modesty. He’s infamous for his ego but he had the humility and wisdom to know that no amount of narration, no matter how elegantly composed or delivered by Orson Welles in thundering voice of God mode could be half as effective in articulating Ford’s brilliance as both a storyteller and a uniquely gifted crafter of painterly images as simply showing selections from Ford’s many towering masterpieces.

Ford may have been a harsh taskmaster and profoundly difficult human being but he created, in his films, a rich world full of violence and brutality but also tenderness, love and humanity. Ford made movies about what it meant to be American but also what it means to be human.

If nothing else, Directed by John Ford should inspire viewers to take a deep dive into the boundless wonders of its ornery subject’s majestic filmography, which could very well be the point in the first place.

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.