Day of the Locust depicts Hollywood as a Circle of Hell

Movies about Hollywood tend to have a love-hate relationship with the industry. Hell, the mere fact that filmmakers feel that the movie-making process is worth making movies about suggests a certain affection for the subject matter, no matter how cynical or dark the approach might be.

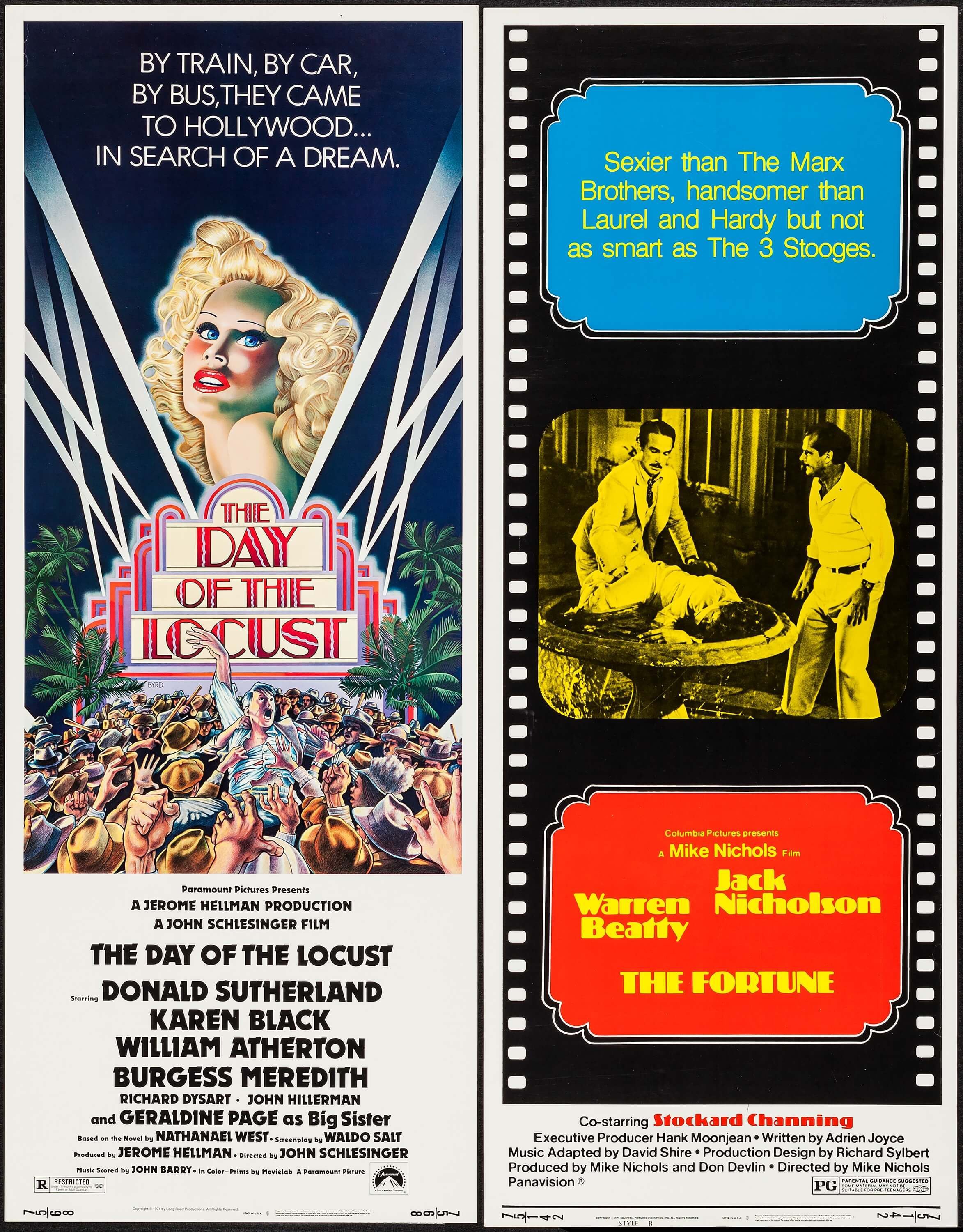

So it’s striking to encounter a movie like 1975’s The Day Of The Locust, director John Schlesinger and screenwriter Waldo Salt’s adaptation of Nathaniel West’s novel, that approaches its subject with only hate, and hate of an unusual intensity.

Oh sure, the Hollywood of the film looks absolutely magnificent. There’s a reason the great Conrad Hall picked up one of the film’s two Oscar nominations for giving the movie a glistening, magic hour sheen. Yet the fact that the people, clothes, sets and scenery are all so lovely somehow just makes the film’s nihilism and seething contempt stand out even more. The Day Of The Locust hauntingly depicts Hollywood as a beautiful place for people with ugly souls. By the film’s end, the malevolent entity known as show-business has thoroughly corrupted everyone it hasn’t destroyed outright. It’s not an industry so much as a great cultural evil.

But before a show-business apocalypse can commence, we are first seduced by the film world’s glamorous facade even as it is apparent that this will not end well for anyone. William Atherton, enjoying a brief stint as a leading man before lucratively recreating himself as the go-to authoritarian asshole heavy in totally 1980s movies like Ghostbusters and Real Genius, stars as Tod Hackett, a recent Yale graduate who arrives in Hollywood to work in movies.

In an apartment complex whose bad vibes and evil mojo would put the Overlook Hotel of The Shining to shame, Tod instantly falls in love with Faye Greener (Karen Black, at her Karen Blackest), a dizzy sexpot intent on making it as a leading lady, but stuck, talent-wise, at the level of a glamorous extra, perhaps permanently. Faye is another of Black’s broken bad girls; she epitomizes show-business in all its beauty, sex and ultimately, sadness.

Black’s genius as an icon as much as an actress was to make sexiness hopelessly, ineffably sad and hopeless and ineffable sadness weirdly sexy. She is half-forgotten these days not because she didn’t deliver memorable performances, but because she delivered unforgettable performances as the wrong kind of women, women who were loose, trashy, wild, and terribly melancholy. Of course it does not help that she delivered some of her best work in movies like the ill-fated adaptation of Portnoy’s Complaint.

Faye’s father is Harry, a former vaudevillian star turned Willy Loman-like traveling salesman played by Burgess Meredith, who doesn’t enter the action until around forty minutes in, and exits it not long after, but not until he’s amply justified the Best Supporting Actor nomination that was the film’s second Oscar nomination.

Like everyone in the film, Harry Greener is broken and directionless, a no-hoper who lugs his case around as he tries to make sales using the same cornball vaudeville tricks that once dazzled the rubes and is greeted by shut doors and glowering expressions.

Meredith gives the character the demented brio of a born trooper, but underneath the manic, pixieish facade, Harry is a horrible human being, a product of his times and the hatreds and fears they engendered. He’s an imp, but with a soul that’s black and wizened like a raisin.

Donald Sutherland rounds out the coterie of tinseltown sad sacks as a numbers cruncher named Homer Simpson who has the misfortune to fall hopelessly in love with Faye around the time she’s made the transition from scheming extra on the fringes to full-on sex worker. Faye is initially into Homer Simpson because he seems to have to have a lot of dough (or d’oh, as it were) but he quickly learns that Faye’s wild spirit cannot be tamed, nor can she be controlled.

It’s a testament to how brilliant Sutherland’s performance is that other characters are constantly saying the name “Homer Simpson” and while it’s distracting at first, on account of that also being the name of the greatest television character of all time, the unfortunate name of Sutherland’s character never breaks the reality of the film.

Homer Simpson is the most innocent character in the film. Hell, he’s probably the only character in the film who is not a racist or a sadist or a would-be rapist. So of course the film, and its angry, Old Testament God, sees fit to punish Homer the most. The squirmy, achingly human vulnerability Sutherland brings to the role, the sense that, unlike the rest of the dreamers and schemers here, he has not developed a hard shell to protect him from the non-stop humiliations of a cruel world, lends an additional pathos to his performance. There is a heartbreaking monologue late in the film where all of the sadness, pain, hurt and confusion Homer has felt about his toxic and one-sided relationship comes to the surface in great, heaving sobs as a good man loses what little hope he has left.

Everything in The Day Of The Locust is corrupt, brutal and cruel, from classy power brokers at the studio getting their jollies watching stag films and participating in cockfights to an evil child actor named Adonis played by a young Jackie Earl Haley bullying adults with sociopathic relentlessness. Haley portrays Adonis as a demonic caricature of a bratty child star. With his bleached platinum curls and never-ending taunts, he’s Little Lord Fauntleroy re-imagined by David Lynch. He’s a child, but in West’s world, childhood is defined less by innocence than sociopathic awfulness. Haley isn’t onscreen for very long but like Meredith, he makes every awful moment count. He’s a figure so infuriating he brings out the evil in the meekest of men, particularly Homer, who is among the casualties in a climax and finale where the incoherent rage lurking just under the surface explodes and civilization gives way to anarchy and madness.

Billy Barty rounds out the film’s trilogy of pint-sized monsters (after the diminutive Meredith and child actor Haley) as a racist hustler on the fringes of show-business life (he drops an N bomb in his first line of dialogue, and doesn’t exactly redeem himself over the course of the film).

Incidentally, Barty also played a racist asshole in golden age Hollywood in the last Fractured Mirror entry, on Under The Rainbow, and while I did not intend for this to be a column about movies where Billy Barty plays a hate monger in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood, it seems to be playing out that way. I promise, however, to take a little time before I cover 1976’s W.C Fields & Company Me, where Barty, in his capacity as the film world’s official little person for decades, also co-starred in.

The Day Of The Locust is less about plot or characterization than it is about mood and tone. It’s less about any individual character than it is about Hollywood and show-business as an almost animistic entity out to destroy the sinners and schemers in its trap. It’s telling that Faye works as an extra rather than a star, since the vastness of Hollywood’s evil and its dark power reduces the poor players of The Day Of The Locust to mere victims caught up in the gears of an evil machine. Their world is vast and unholy; the players are timid, tiny and weak.

If The Day Of The Locust isn’t the single most despairing and apocalyptic depiction of the filmi industry in American film history, then it’s definitely in the top five. It is customary for movies about movies to depict show business as sleazy, amoral realm of hustlers, parasites and opportunists. The Day Of The Locust goes much further to depict the Hollywood of the 1930s as a glistening, seductive dream factory from the outside and the ninth circle of hell from the inside.

The Day Of The Locust surveys a contemporary Sodom & Gomorrah where an enraged God punishes the orgy of sin that is the film industry by swallowing up people and sets and buildings in earthquakes that here feel like a deadly manifestation of the lord’s righteous wrath. The Day Of The Locust doesn’t devolve into hell, since it’s convincingly inhabited hell all along, and Hall gives his Hollywood dream/hellscape the devil’s own deceptive charm.

Schlesinger’s film is brutal and uncompromising throughout, but in its fiery finale it doubles down on its depiction of Hollywood as Hell and show-business as pure evil with a ferocity that’s difficult to shake off. Even for a new Hollywood enraptured with edginess, The Day Of The Locust is bracingly dark.

The film might have been too dark even for the adventurous audiences of the time. Atherton is probably the closest thing the movie has to a hero, and he tries to sexually assault Faye before revealing himself to be a drunken, belligerent asshole. Hollywood likes to pretend to make fun of itself while actually feeding its enormous ego and sense of its own inflated importance. The Day Of The Locust, in sharp contrast, doesn’t let anyone off easily, including the audience and the industry it chronicles with such visceral disgust.

The grim black comedy and serrated satire of The Day Of The Locust cut, and cut deep, making it a tough but rewarding watch over four decades after its release.

Wanna read a book full of pieces like this? Of COURSE you do! Pre-order The Fractured Mirror, the Happy Place’s next book, a 600 page magnum opus about American films about American films, illustrated by the great Felipe Sobreiro over at https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!