The Great Hal Ashby Debuted with the Lovely Comedy-Drama The Landlord and Ended Grimly with 8 Million Ways to Die

When Hal Ashby made the big jump to directing with the help of mentor and frequent collaborator Norman Jewison with the 1970 interracial comedy-drama The Landlord he was already an Academy Winning hotshot filmmaker who had left an indelible imprint on American film as an editor.

Ashby won his Academy Award for the scorchingly intense 1967 interracial cop drama In the Heat of the Night and was nominated for The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming, both of which were directed by Jewison. Ashby made a distinct impression with his first collaboration with Jewison, 1965’s The Cincinnati Kid but his most important and influential work with Jewison was the dreamy 1968 romantic heist The Thomas Crown Affair, which aggressively experimented with split screens that shattered the frame into jagged pieces all competing for the audience’s attention.

Ashby and his fellow editors played such a huge role in establishing the look and feel of the iconic cult classic that it seemed to belong to them as much as it did its director or its screenwriter.

Through his groundbreaking work with Jewison, a filmmaker whose work never had quite the same energy or innovation without Ashby in the cutting room, Ashby took editing in mainstream studio films about as far as it could go.

Jewison decided that Ashby was ready to direct so he produced an adaptation of Kristin Hunter’s 1966 novel The Landlord adapted by Bill Gunn, a black actor best known for writing and starring in Ganga & Hess.

Like In the Heat of the Night, The Landlord is about race relations, a controversial, hot button subject then, now and forever. Both films explore our country’s unique melting pot but where In the Heat of the Night was pitched at a roiling boil The Landlord maintains a low simmer throughout.

The melting pot aspect extends to the film’s creative team. It’s interracial in a way that was unusual at the time and remains unusual today: the director and producer are white, as is star Beau Bridges but its screenwriter is a black man adapting a novel by a black woman and The Landlord’s supporting cast is overwhelmingly black.

Decades before he became the king of TV movies, Beau Bridges starred in The Landlord as Elgar Winthrop Julius Enders, a twenty-nine year old child of privilege every bit as wealthy and pampered as his name would suggest.

In a wonderful turn of phrase, one of the many, many people way down the socioeconomic ladder from him describes Elgar’s existence as “casual.” That is the perfect description for the handsome, agreeable young man’s charmed life.

Because he is the scion of a wealthy, powerful family, Elgar doesn’t really have to worry about anything. He doesn’t have to worry about a job or finding a place to live since he can seemingly crash with his indulgent parents indefinitely. He doesn’t have to think about money or class because he has more than he’ll ever need just by virtue of being born to the right parents, nor does he have to think about race or sex or politics.

That all changes when Elgar decides to buy a tenement in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn with an eye towards kicking out its current inhabitants and building himself a sweet-ass pad to help assist in the gentrification of the neighborhood.

He does not seem to realize that the residents of his new property have zero interest in moving out. Instead of treating the new owner of the building with deference, they treat him with casual disdain, as a consummate outsider who has no idea what he’s gotten himself into.

Like Harold & Maude, The Landlord depicts what can generously be deemed “white culture” as an absence of culture, not to mention soul, authenticity and humanity. The glimpses we get into Elgar’s life outside of the tenement are surreal in their disconnect from life as it is lived by most folks. The lives of the tenants of the tenement are real and urgent and complicated; the pampered existences of Algar, his family and his social circle, in sharp contrast, feel like an impossible fantasy.

Being responsible for other human beings, namely his tenants, changes Elgar. It forces him to leave the womb-like comfort of his previous life, when he interacted with black people only when they were serving him food or cleaning up after him, and truly engage with New York in all of its wonder and squalor and mystery.

The rich young man falls in love and lust with a pair of very different tenants: Lanie (Marki Bey), a glamorous biracial dancer so light-skinned that she can pass for white and Francine "Fanny" Johnson (Diana Sands), the quick-witted wife of activist Copee Johnson (Louis Gossett Jr.), who copes very badly with the news that his wife has been impregnated by her white landlord.

Even at the very beginning of his career as a director Hal Ashby had a genius for telling profoundly human stories that eschewed cliche and convention and stereotype in search of truths about who we are as a nation, individually and collectively.

The Landlord takes place in the kind of pre-gentrification New York streets that non-blaxploitation movies otherwise ignored and is populated by the kind of complex, working-class black characters that were similarly invisible in mainstream movies.

Ashby made movies overflowing with empathy and compassion, curiosity and warmth. His background as an editor helped him tell new kinds of stories in new kinds of ways, that combined sound and image in ways that were casually revolutionary.

Ashby would make many different kinds of movies in the 1970s but they all share a fascination with human nature and an underlying sense of gentleness. As famously profane as The Last Detail is, at its core it is a very tender love story between men.

It’s tempting to call the legendary filmmaker’s final feature film, 1986’s 8 Million Ways to Die, an adaptation of Lawrence Block’s hardboiled 1982 novel, a departure for Ashby since it’s a sleazy action movie instead of a gorgeously melancholy, bittersweet comedy-drama.

But one of the many things that made the filmmaker unique and remarkable is that there is no such thing as a typical Hal Ashby movie. Ashby was never one to stick with a particular genre or type of film for too long, or at all.

Over the course of his extraordinary and all too brief career as a director Ashby explored gentle culture clash comedy (The Landlord), quirky, darkly comic inter-generational romance (Harold & Maude), gleefully profane Naval comedy-drama (The Last Detail), satirical sex comedy (Shampoo), biography (the Woody Guthrie biopic Bound for Glory), socially conscious message movies (Coming Home) and transcendent political and social satire (Being There). And that’s just his 1970s!

Like many archetypal 1970s filmmakers, Ashby struggled in subsequent decades. The 1980s were particularly brutal as he wrestled with cocaine addiction, released a string of flops (1981’s Second Hand Hearts, 1982’s Looking To Get Out and 1985’s The Slugger’s Wife) and watched helplessly as Tootsie, a project he’d worked on and developed for years became a huge, iconic hit with Sydney Pollack in the director’s chair.

Ashby will forever be synonymous with the 1970s but 8 Million Ways to Die is a quintessential 1980s movie, a pulpy, lurid, hyper-masculine crime melodrama in the mold of Scarface and To Live and Die in L.A with an icy synthetic score redolent of the ominous majesty of Tangerine Dream, Giorgio Moroder and John Carpenter from the formidable screenwriting team of Oliver Stone, an uncredited Robert Towne and novelist and Road House scribe R. Lance Hill.

8 Million Ways opens with an ambitious, unbroken helicopter shot set to James Newton Howard’s sinister synthesizer-fueled score that establishes its setting of Los Angeles in the middle of the Reagan decade as a cold and lonely place, vast, ominous and full of darkness and danger.

As the film opens, protagonist Sheriff Matt Scudder (Jeff Bridges, brother of Ashby’s first leading man) is deep into his addiction as an alcoholic. So before he leads a raid he takes a deep drink from his flask for a little liquid courage before fatally shooting and killing a small time criminal in front of the man’s horrified wife and children.

The trauma and guilt lead Scudder on a massive bender that finishes ruining what’s left of his professional and personal life. The bleary booze binge destroys Matt’s marriage, imperils his relationship with his daughter and costs him his job.

The troubled cop with a drinking problem who gets on the wagon and then tumbles off it is an exhausted cop movie cliche. Yet Ashby, who knew way too much about what it felt like to be ruled by self-destructive compulsions beyond your control makes Matt’s battle with alcoholism the film’s emotional core. This is a movie about addiction and sobriety as much as it is about murder, drugs and prostitution.

Bridges is a beautiful human being and one of the most effortlessly charismatic leading men ever to grace the big screen but when the former cop is drunk or recovering from one of his epic benders he doesn’t just look bad: he looks like death. He looks like a man who is just barely holding it together. He looks downright pathetic. Ashby and Bridges don’t shy away from the ugliness and degradation of addiction in all its forms.

Our rough-edged protagonist’s blackouts are particularly brutal; it’s one thing to investigate someone else’s murder; it’s quite another to solve the more urgent mystery of what the hell you’ve been doing during days lost forever to the black hole of addiction.

The newly sober ex-Sheriff stumbles into the messy life of Sunny (Alexandra Paul), a high priced call girl who offers to pay him handsomely to protect her from small time criminal Willie "Chance" Walker (Randy Brooks).

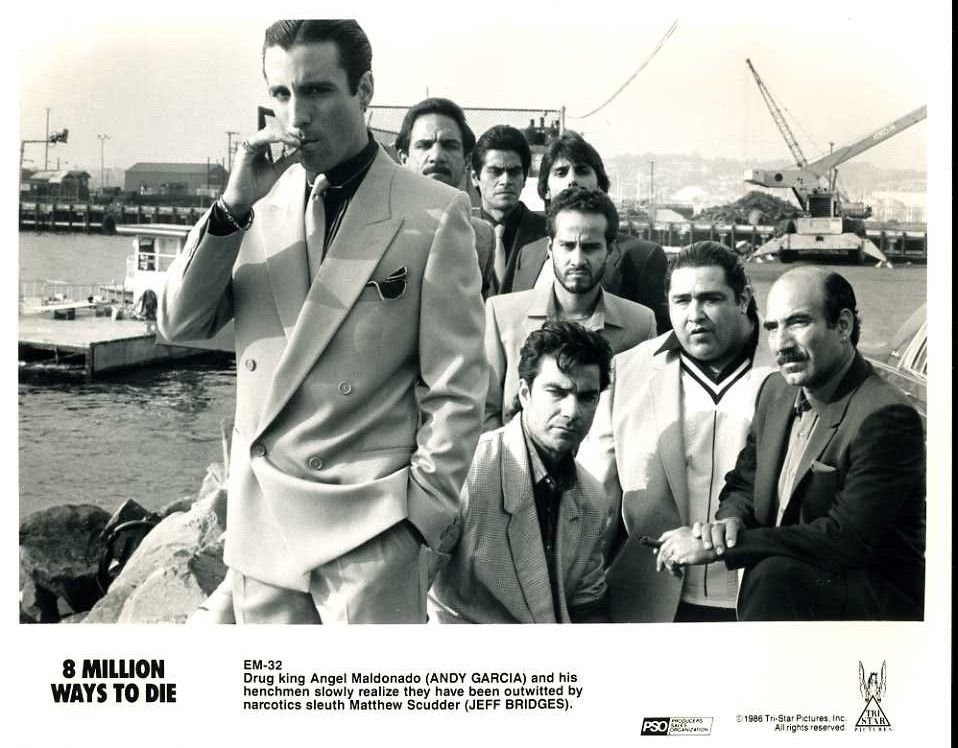

When Sunny is brutally murdered it sends Matt on another dangerous, destructive, days-long bender. When he comes to in a drunk ward he begins an investigation into Sunny’s murder that leads him to believe the culprit is not Chance but rather drug dealer Angel Moldonado (Andy Garcia).

In keeping with the problematic sexual politics of the time, our scraggly hero spends a fair amount of the film insulting sex workers for being sex workers. This is true of both Sunny and her colleague Sarah (a tough and terrific Rosanna Arquette), a hard-edged prostitute Matt befriends after Sunny’s death.

In keeping with the film’s refreshingly honest take on the downside of alcohol, a deeply inebriated Sarah tries to lure Matt into bed out of both sexual desire and boredom only to vomit on him very early in the failed seduction attempt. This understandably proves a deal-breaker for Matt and reminds him why he gave up drinking and is committed to the righteous road of sobriety no matter how difficult it might prove.

A complicated love affair soon develops between Matt, Angel and Sarah although a man like Angel is as incapable of love as he is of kindness. He’s less interested in loving Sarah than in controlling her.

Garcia’s rocket ride to superstardom would not begun until a year after 8 Million Ways to Die flopped, putting the final nail in the coffin of its director’s film career, when he appeared in The Untouchables followed by Stand and Deliver, Internal Affairs and his Oscar-nominated turn in The Godfather Part III.

8 Million Ways to Die should have been Garcia’s star-making film. His hair slicked back into a very 1980s ponytail, his svelte frame squeezed into expensive, impeccably tailored suits, Garcia plays Angel as the gregarious, schmoozing, outgoing face of pure evil.

He’s a grinning barracuda of a man whose game is seduction as much as it is cocaine; he’s the kind of charming, sociable sociopath who will smile in your face and cut your throat at the same time.

Garcia completely dominates 8 Million Ways to Die’s second half, as our now sober and focused hero’s obsession with saving Sarah’s life and avenging Sunny’s death puts him on a collision course with a suave lunatic who thinks nothing of killing someone to make a point.

8 Million Ways to Die’s absurdly overqualified cast and creative team elevate a tawdry tale of pimps and prostitutes, cocaine and murder, ex-cops and career criminals even as Ashby’s lurid fever dream of an action-thriller never quite manages to transcend its trashy origins as the kind of paperback businessmen take with them on airplanes to pass the time.

Ashby never lost his gift for storytelling and immersing audiences in fully-realized cinematic worlds but at a certain point the world seemed to have stopped paying attention to his troubled new films even as his 70s output made him a god to multiple generations of cinephiles.

Check out The Joy of Trash: Flaming Garbage Fire Extended Edition at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop and get a free, signed "Weird Al” Yankovic-themed coloring book for free! Just 18.75, shipping and taxes included! Or, for just 25 dollars, you can get a hardcover “Joy of Positivity 2: The New Batch” edition signed (by Felipe and myself) and numbered (to 50) copy with a hand-written recommendation from me within its pages. It’s truly a one-of-a-kind collectible!

I’ve also written multiple versions of my many books about “Weird Al” Yankovic that you can buy here: https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash from Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Joy-Trash-Nathan-Definitive-Everything/dp/B09NR9NTB4/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr= but why would you want to do that?

Check out my new Substack at https://nathanrabin.substack.com/

And we would love it if you would pledge to the site’s Patreon as well. https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace