Ernest in his Entirety: a 14,000 Word Guide to the Ernest P. Worrell Films

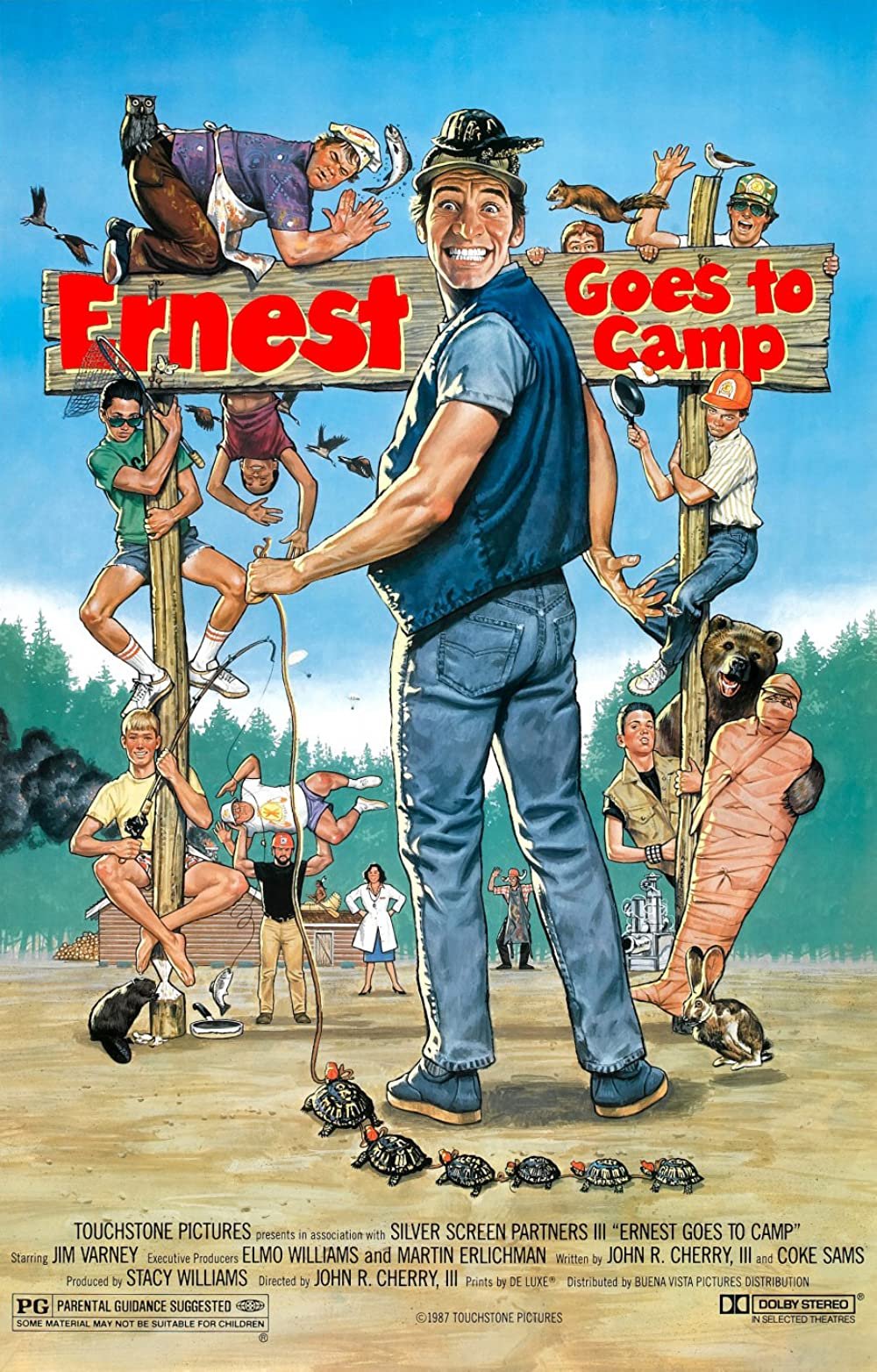

Ernest Goes to Camp (1987)

I was shocked and disgusted to discover that 1987’s Ernest Goes to Camp is not available legally through streaming in God’s own United States. I don’t want to say that this alone single-handedly invalidates streaming but any home video medium that cannot facilitate the easy and legal viewing of Ernest Goes to Camp is fatally flawed.

We as a society NEED free and easy access to Ernest Goes to Camp. It’s IMPORTANT. Children need Ernest P. Worrell’s first cinematic vehicle so that they might experience joy the likes of which they never imagined possible but also so that they might learn from it as well.

In his own unpretentious way, Ernest P. Worrell has much to teach us about what it means to be human. He isn’t just an unusually American pop culture icon. No, Ernest P. Worrell IS America.

Ernest P. Worrell represents everything that’s good about the American character: our indefatigable optimism, can-do spirit, irrepressible ambition and homespun, folksy charm and good humor. Yet for reasons I cannot begin to fathom the Ernest-loving masses need to buy old-fashioned DVDs in order to experience a cinematic debut that shook the world like none since Citizen Kane.

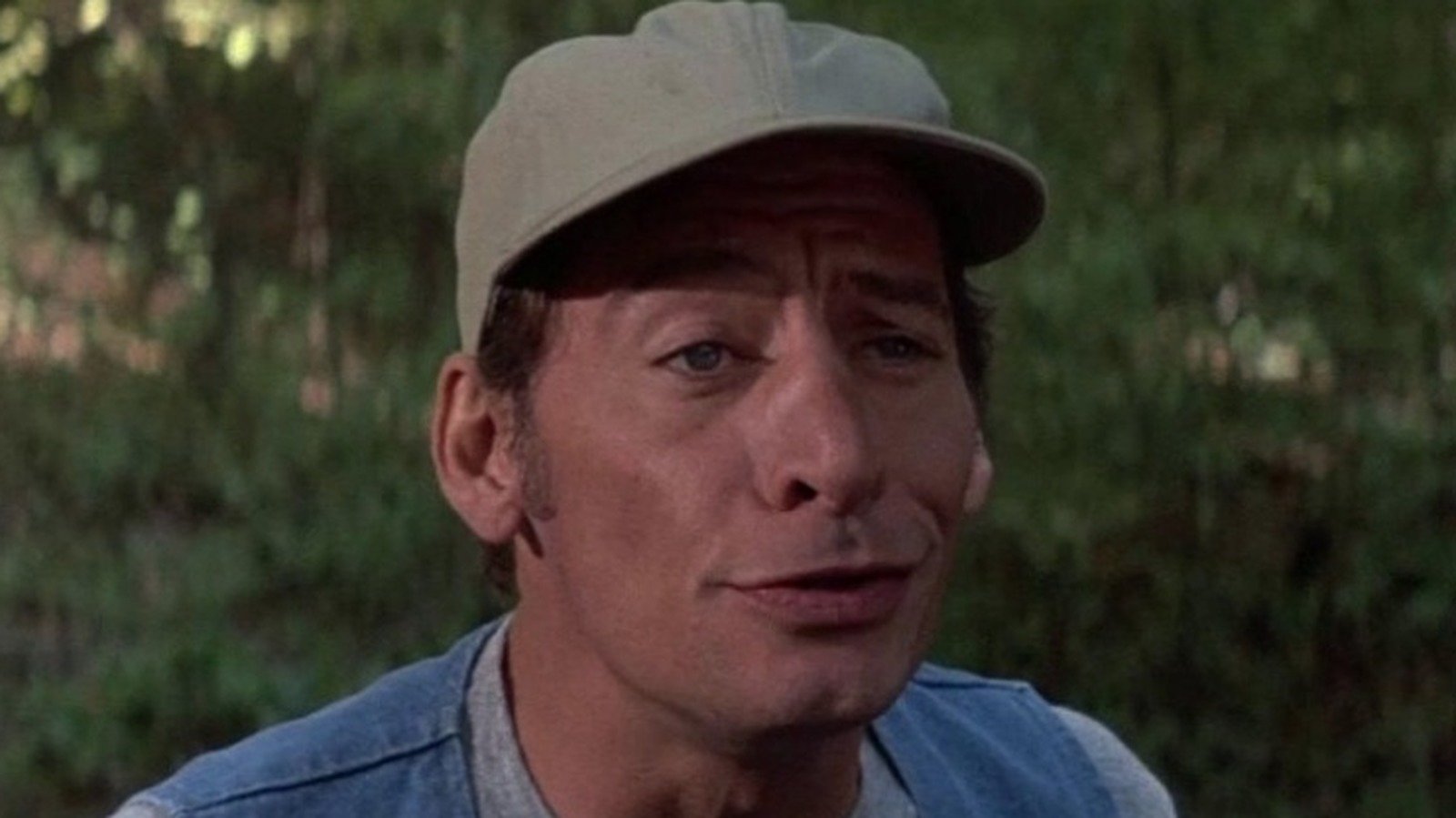

I don’t want to sound like Armond White writing about Adam Sandler but Jim Varney is the only true genius our country has ever produced. He is the quintessential common man, a denim-clad working class hero and son of the South beloved by the REAL AMERICANS who make our country great: long-haul truckers, Waffle House employees and Juggalos.

Compare that to a lesser artist and thinker like Paul Thomas Anderson, who makes movies only for the moneyed, cultured elites. Ernest P. Worrell—the character, not Jim Varney—could easily make a movie like The Master but Anderson could never create something like Ernest Goes to Africa.

Ernest made movies that give the suffering masses escape and a reason to live. Paul Thomas Anderson makes movies exclusively for Noah Baumbach’s late mother. Who is the greater artist? No one can say but it’s clearly Ernest.

In Ernest Goes to Camp Jim Varney plays Ernest as an unassuming man with a dream. Though he toils happily as a much-abused handyman and janitor at Camp Kickakee, he aspires to the ostensibly more dignified job of counselor.

It’s okay to be working class in movies like this as long as you long for something more. So a janitor has to dream of being a camp counselor, who in turn must long to be head counselor. The head counselor must then aspire to own a camp someday while a camp owner would probably look back longingly at his time as a handy-man/janitor.

Varney honed the character of Ernest through the last legitimate American art form: local television commercials. The popularity and visibility he attained through his work as a ubiquitous and in-demand pitchman from 1980 onward afforded him an opportunity to make the leap into the truest and most American of cinematic sub-genres: the slobs versus snobs summer camp comedy.

The snobs are the WASPy campers and counselors of Camp Kikakee, who abuse Ernest physically and emotionally. The lovable everyman just wants to fit in and be accepted and must endure an endless gauntlet of humiliation as a result.

No matter how badly he’s treated, Ernest never loses his positive attitude or lust for life. He’s Christ-like in his selflessness and ability to withstand the worst humanity has to offer without losing faith or giving into darkness or cynicism.

The slobs are the outcasts of the State Institute for Boys. They’re the juvenile delinquents of today and the full-on felons of tomorrow. They’re the human scum who will rob your grandmother’s retirement home, set homeless people on fire and execute low-level Ponzi schemes.

At least that’s how they’re treated by the popular, snobby counselors: as sub-human riff-raff fit only for incarceration. The only person who believes in these boys is Ernest, a natural friend and ally of the underdog.

The surly rebels from the State Institute for Boys are decked out in the height of New Wave fashion circa 1982. They look like members of Kajagoogoo’s entourage with their totally eighties shades, ties over tee-shirts, Summer vests and sports coats/ football tee shirt combos.

And half-shirts! So, so many half-shirts on embarrassed-looking children!

The top counselor at Camp Kikakee is initially put in charge of the rebels from the State Institute for Boys but when he decides to drown an African-American child by throwing him into deep water despite knowing that he can’t swim Ernest is promoted.

The slobs have a strategic partnership with the Native Americans who own the land Camp Kikakee rents every summer, more specifically Old Indian 'Chief St. Cloud’ (Iron Eyes Cody), one of only two surviving members of a once-mighty tribe.

For decades, Cody was one of the most ubiquitous and popular Native American character actors around. He was more or less a professional Native American best known for his roles in the 1948 Bob Hope comedy Paleface and for playing the Native American who weeps with despair about littering in a popular series of public service announcements in the 1970s.

The only problem was that a man who pretty much only played Native Americans wasn’t actually Native American. Not in the least. No, Iron Eyes Cody was instead Sicilian but that didn’t keep him from cashing in on his non-heritage all the same.

When I went to summer camp around the time Ernest Goes to Camp takes place it was common for my fellow campers to claim Native American heritage. Everyone was one sixteenth Sioux, or somehow Lakota somewhere on their mother’s side.

These fake Indians and wannabe Indians reflected the tacky, oblivious appropriation of Native American life and lore at the heart of so many half-ass summer camps. In Ernest Goes to Camp, the soulful caricature of a wise old Indian played by Hollywood’s preeminent fake Indian explicitly deems white children in New Wave garb the true heirs of his fallen brothers and sisters.

Chief Big Faker’s granddaughter tells a parasite interested in their valuable land, “My grandfather thinks of those boys as young braves who keep alive the tradition of our ancestors.”

Ernest Goes to Camp delivers the inclusive message that you don’t actually have to be Native American in order to, you know, be Native American. You just need to have the right spirit, make a headdress and/or teepee, chant something that sounds indigenous and boom, you embody the proud essence of the Lakota warrior despite being a weird asthmatic Jewish kid who smells like pee.

The State Institute for Boys rejects repay Ernest kindness and belief with unrelenting cruelty but Ernest’s spirit, his mighty, mighty spirit is not crushed until he’s fired from his dream job due to a combination of sabotage and incompetence.

Then something unexpected and wonderful happens: Ernest P. Worrell sings. Ernest doesn’t just sing; Ernest sings from the heart. Ernest sings from the soul. Ernest sings a tender ballad about the overwhelming despair and melancholy coursing through his being without even the faintest hint of humor.

Ernest Goes to Camp aims unabashedly for pathos in a way that could easily be cringe-inducing and embarrassing but instead is enormously powerful and moving.

It’s yet another illustration that actor playing the titular cornball is semi-furtively an extraordinarily talented, versatile performer who could do a whole lot more than engage in cornpone hijnks but seldom had an opportunity to show what he was truly capable of.

The primary villain in Ernest Goes to Camp is played, appropriately and inevitably enough, by John Vernon, the ultimate glowering WASP heavy thanks to his iconic turn as the Dean in Animal House.

Sherman Krader is the head of an evil mining corporation who wants the land the camp is on because it has a valuable mineral known as Petrocite and, in the film’s climax, goes to war with Ernest’s campers, who Old Indian 'Chief St. Cloud’ deputizes as emergency Native Americans so that they can wage fiery, righteous holy war against Krader and his paleface infidels.

In a dazzlingly offensive climax, it turns out that Ernest P. Worrell, humorously incompetent caucasian and super-cracker, embodies the heroic essence of the righteous Native American warrior because the Holy Spirit protects him from Krader’s bullets.

Because Ernest Goes to Camp is a Touchstone production from 1987 it also includes multiple inspirational montages set to pop songs with lyrics like, “Fighting for the rights of dreamers!/Brave Hearts, You and me, we are the true believers!/We’re gonna make it together/Others may fail we say never!”

Ernest Goes to Camp made Varney a slapstick superstar but his performance is defined as much by his underrated flair for verbal comedy, particularly in the character’s penchant for grandiosity and verbosity.

Ernest talks for the pleasure of talking. He seems only vaguely conscious of the words tumbling out of his mouth, like when he’s getting a shot and, in his terror, confesses to both stealing the Lindberg baby AND being Nazi butcher Josef Mengele.

Later he favors his campers with an undoubtedly fictional account of his time in the shit in Vietnam. In scattered moments like these, Ernest Goes to Camp aspires to do more than just amuse slow-witted children and succeeds.

I have now seen Ernest Goes to Camp two and a half times and am still surprised and delighted by it. Childhood nostalgia undoubtedly plays a role but I also genuinely think Varney is comic genius as well as an absurdly likable performer seemingly without a mean or a fake bone in his rubbery body.

Ernest Saves Christmas (1988)

When I first covered the 1988 sleeper hit Ernest Saves Christmas for Control Nathan Rabin 4.0, the column on my website where readers choose movies for me to watch and write about for a modest price, I remember being wonderfully surprised by it.

I was shocked by how much I enjoyed the film. It was the one that turned me into a true believer, an unabashed Ernest P. Worrell fan, an enthusiastic appreciator of the only true genius this country has ever produced.

But I was also surprised by LOTS of individual choices the film made, primarily in terms of its depiction of Santa Claus. Most movies about Kris Kringle understandably depict him as hyper-efficient.

He has an AWFULLY big operation to run, after all, and a very narrow window—a single late December evening—to unload an insane amount of inventory to a broad and diverse customer base.

So Santa Claus is traditionally depicted as someone who has his shit together and can be trusted to literally accomplish super-human feats. He’s the ultimate manager and the best employee any organization could hope for.

That’s not the Santa Claus of Ernest Saves Christmas, fascinatingly enough. The cult comedy’s unique take on Saint Nick is a lovely human being, a Prince of a Man, really. He’s the literal personification of Christmas magic.

But he does NOT have his shit together. He’s easily confused. He possesses God-like omniscience yet he mistakes play money for the real thing. He loses prized possessions like the magic sack that is the key to so many of his powers at an alarming rate.

Father Christmas is disturbingly reliant upon the problem-solving and quick thinking of noted dullard Ernest P. Worrell. When the kindly toy baron tells people that he’s Santa Claus and they look at him like he’s insane they don’t seem entirely wrong in that estimation.

Unlike pretty much ALL other versions of the iconic gift-giver, this Santa Claus flies commercial and loses his flying reindeer along with everything else. In a glaring case of poor judgment, the absent-minded Yuletide titan needs to hand over the torch to a new Santa Claus by seven o’ clock but doesn’t even begin the process of trying to convince his choice, soft-hearted children’s entertainer Joe Carruthers (Oliver Clark) to take the gig until that afternoon.

That’s NOWHERE near enough time! What was he thinking!?! It’s probably a good thing he’s giving up the gig because he’s undeniably losing it.

Santa Claus’ tragic inability to cope with the complexities and demands of our crazy-making modern world lands him in prison, not unlike Ernest himself in the film that would follow, 1990’s Ernest Goes to Jail.

I’m sure there are drafts of Ernest Saves Christmas where Santa Claus gets shanked with a sharpened candy cane or agrees to become someone’s prison bitch in exchange for protection but this keeps things PG.

Ernest Saves Christmas’ Santa Claus is merely mesmerizingly off-brand yet somehow still true to the sentimental, twinkly spirit of the season, not a brutalized victim of our nation’s prison-industrial complex.

On the contrary, when he thinks that Christmas is being disrespected or over-commercialized, this renegade Kris Kringle isn’t afraid to throw hands and beat a non-believing motherfucker up.

Ernest Saves Christmas is so filled with surprises and wonderfully daft choices that I forgot some pretty huge ones.

For example I forgot that Ernest Saves Christmas is a movie about the filmmaking industry and I am writing a massive book about the history of movies about movies.

Despite my obsession with this juiciest of subjects, I didn’t recall that the dynamic duo of Ernest P. Worrell, good-natured idiot, and Santa Claus, senile bumbler, save Christmas by sabotaging the Orlando-based production of a Christmas-themed horror movie by stealing its lead actor.

Being set in the sweltering heat and pounding sun of Orlando, Florida somehow did not keep Ernest Saves Christmas from being about a holiday synonymous with snow and cold weather. Why should it keep Ernest Saves Christmas from being about the movie business as well just because it takes place thousands of miles away from Hollywood?

In Ernest Saves Christmas the fate of Christmas for eternity hinges on outcasts cruelly depriving a sleazy Florida film production of crucial personnel deep into the production process.

Ernest Saves Christmas is a film of surprises, beginning with its slender, senile, soon to be imprisoned Santa arriving in Orlando, Florida via a commercial airline and promptly forgetting his magical sack in the taxicab of good-hearted goof Ernest P. Worrell.

Giving the seemingly deluded old man a lift gets Ernest fired on Christmas Eve. Santa, meanwhile, ends up in prison for vagrancy. At first it looks like the massive, menacing prisoners will beat the old man to a pulp but they’re not immune to the Christmas spirit. The magical old man with the twinkle in his eyes transforms these junkyard dogs into well-mannered puppies overcome with appreciation for the season’s gifts, only some of which are literal.

One of the great joys of watching this most auspicious of film series comes from seeing Varney stretch his formidable talents by playing different kinds of characters

In Ernest Goes to Jail that’s accomplished by having Varney play a dual role as both the hero and villain. In Ernest Saves Christmas, Ernest is an unlikely master of disguise and dialects, just like the actor playing him and also Dana Carvey’s iconic Pistachio Disguisey’s in 2002’s Master of Disguise.

Ernest Poindexters up to play a sniveling sycophant of the governor in order to get Santa Claus sprung from the hoosegow. Like Bugs Bunny before him, Ernest dresses in drag as at the slightest provocation.

The Ernest franchise understood that silly men dressing up in women’s clothing was one of the unassailable bedrocks of comedy. It’s as American as mom, baseball, apple pie and Milton Berle’s enormous penis.

In order to get into a studio lot where Christmas Slay is being filmed on Christmas Eve, with a cast of traumatized children, Ernest pretends to be a snake wrangler who has been dealing with snakes for so long that he himself seems to have de-evolved into a feral, sub-human state.

Varney’s Ernest is a gleeful hurricane of destruction happily oblivious to the mayhem he leaves in his wake. There’s a bravura physical comedy set-piece where Ernest visits his forever unseen acquaintance Vern’s home and accidentally but absolutely trashes it with an idiot grin on his face the whole time.

Santa Claus has traveled to Florida to convince actor Joe Carruthers, the longtime host of a longtime children’s show about the importance of manners, to accept the existential burden of taking over the ultimate hardest job you’ll ever love but the middle aged man is finding it hard to say no to a lead role in a feature film entitled Christmas Slay, albeit one that can hardly be called a major motion picture.

There’s nothing children like more than movies about weird, seemingly childless yet child-obsessed men of a certain age at a personal and professional crossroads who must choose between late in the game movie stardom and becoming an ageless figure of Christian mythology.

The only possible exception are stories about succession, how a job or position changes hands after someone retires or moves on.

For a Christmas movie about kiddie favorites Ernest P. Worrell and Santa Claus, Ernest Saves Christmas is curiously light on actual children though it does have a troubled teenaged hero in Pamela Trenton / Harmony Starr (Noelle Parker), a runaway who steals Santa’s magic sack with hopes of untold wealth and riches and comes to regret stealing from a magical being who literally embodies goodness, generosity and the Christmas spirit.

Ernest Saves Christmas is an atypical Christmas movie but it ends on a traditional note with Ernest commandeering a magical flying sleigh that has been conspicuously absent all film long and the new appointee Santa Claus happily accepting his new gig, leaving the schlockmeisters behind Christmas Slay without a lead actor.

That doesn’t seem very compassionate to me but then Ernest and Santa clearly care more about Christmas than they do Christmas Slay’s bottom line.

Ernest Saves Christmas marks a distinct improvement over Ernest’s wildly over-achieving debut. It’s unusual Christmas fare that nevertheless delivers the holiday goods in abundance.

It’s daffy and likable and sweet and sincere without feeling cloying or maudlin. Critics and intellectuals might not have appreciated or understood Ernest. When they looked at him decked out in denim they saw only a fool and an idiot, not a hero willing to debase himself for the greater good, for our delight and enjoyment.

The people understood, however, and Ernest Saves Christmas was both a sizable hit and a beloved Christmas classic, the kind of movie you can watch over and over and over and over and over again and find new things to dig each time around.

Ernest Goes to Jail (1990)

The character of Ernest P. Worrell, lovable denim-clad goober, wasn’t just commercial in the sense of appealing to a broad mainstream audience. He was also commercial in that he was specifically created by the Nashville-based Carden & Cherry Advertising Agency to sell products.

When it came to selling people crap they don’t need, Jim Varney proved a savant. The rubber-faced, elastic-limbed comic genius and hero to children everywhere had a photographic memory that allowed him to memorize scripts almost instantly and crank out dozens of versions of a spot over the course of a single day.

Ernest was a creature of commerce. He was a pure pitchman spawned at the dawn of the Reagan decade to sell a wide variety of products, goods and services on both the local and national level.

Jim Varney refined and perfected the character of Ernest P. Worrell during his early days as a prolific, popular and in-demand pitchman. By the time Ernest made his starring debut in 1987’s Ernest Goes to Camp Varney had been playing the trash icon for seven years. He had attained mastery. He was a physical comedy virtuoso equally adept at lightning-fast, dazzlingly precise verbal humor.

That’s one of the many things that I find fascinating about Varney’s portrayal of Ernest P. Worrell. He’s understandably seen primarily as a sturdy vessel for slapstick shenanigans but he’s also blessed with a seemingly incongruous streak of verbosity and grandiosity.

Ernest P. Worrell is a quintessential small guy with big dreams. In 1990’s Ernest Goes to Jail, the ambitious janitor proudly proclaims, with a look of furious determination, “I am Ernest P. Worrell, an upwardly mobile American at his best. And I know that if I pay my taxes, bathe and floss regularly, I will ascend the ladder of success, head over foot.”

For the pratfall-prone working man, ascending the ladder of success means getting a white-collar job as a clerk at the bank he cleans. In American movies it’s okay be to working class only if you’re aggressively and publicly striving to be more successful.

Ernest does not let the fact that he is uniquely inept at his job keep him from dreaming of something more. While cleaning the bank one fateful day the floor polisher Ernest is using goes haywire in ways generally not seen outside of Saturday morning cartoons.

The metal monstrosity seemingly gains sentience and takes on a life of its own. It’s so preposterously powerful that it upends the law of gravity and pulls Ernest across the floor and up a wall to the ceiling.

An overwhelmed and unbelieving Ernest yells at the floor polisher, “You can’t go up walls!” as it proceeds to do just that.

It’s as if Ernest is heckling his own movie by explicitly singling out one of the many moments when it leaves the dreary world as we know it and enters a crazy realm of cartoon fantasy where anything is possible and the laws of God and man no longer apply.

At the risk of hyperbole, the set-piece where Ernest’s floor polisher goes crazy, destroys the bank and zooms up a wall in violent defiance of everything we know about physics and gravity is a masterpiece of physical comedy on par with the best of Charlie Chaplin and Jaques Tati.

Ernest Goes to Jail briefly turns into Maximum Overdrive as machines and inanimate objects seemingly come to life in order to terrorize Ernest. But they also give him incredible, incredibly poorly defined powers.

From that moment on Ernest P. Worrell, incompetent janitor and aspiring bank clerk, has a unique and unpredictable relationship with magnets and electricity that changes constantly according to the needs of the plot.

This causes problems on Ernest’s non-date date with bank employee Charlotte Sparrow, a coworker he has a crush on. Ernest’s love interest here is played by an actress named Barbara Bush.

Yes, Barbara Bush. When Ernest Goes to Camp was released in 1990 the First Lady was also named Barbara Bush, but that somehow did not keep the actress from changing her name until later in her career.

That would be like watching a new movie with a leading lady named Jill Biden, Michelle Obama or Melania Trump: distracting!

As its title suggests, Ernest Goes to Jail is ultimately not a movie about a hillbilly who wants to be a bank clerk or a lowbrow romp about a redneck goober who becomes a human magnet when narratively convenient.

Ernest Goes to Jail is instead a story about Ernest going to the big house and a violent criminal escaping certain death. Ernest happens to be a dead ringer for Felix Nash (Varney in a challenging double role), a career criminal sentenced to death by electrocution for his crimes against humanity.

When the glowering career criminal’s flunky Rubin Bartlett (Barry Scott) goes on trial for murdering a fellow inmate Ernest ends up serving as a juror for the trial. That is one heck of a coincidence but then Ernest Goes to Jail has no use for realism, plausibility or verisimilitude. It’s a live-action cartoon with a goofy anti-logic all its own.

Rubin decides to take advantage of Ernest’s uncanny, some might even say wildly implausible resemblance to Felix Nash to spring him from prison. In yet another unrealistic development, Rubin’s lawyer convinces the judge to move matters to the prison where the murder took place.

There, an oblivious Ernest is bonked on the head, stripped of his signature attire and dressed up in Felix Nash’s jumpsuit so that the condemned criminal can escape prison in Ernest’s trademark duds and live his life.

Ernest is so oblivious that it takes him a good ten minutes to realize that he is a prisoner in jail and not being sequestered in an unusual hotel.

Jim Varney’s endlessly enthusiastic pop icon is an overgrown, emotionally stunted man-child beloved by children and simple-minded adults like myself.

So it’s striking that Ernest Goes to Jail is a kiddie slapstick comedy completely devoid of children. The setting lends the proceedings an unmistakably adult air, as does Varney’s relatively deadpan, straightforward portrayal of Felix Nash as a murderous sociopath.

After escaping prison and a date with the electric chair, Felix attempts to force himself on Charlotte Sparrow, then proceeds to drop Ernest’s beloved dog Rebound in the trash.

An attempted sexual assault has no place in an Ernest movie, even one set primarily in a prison. Ernest is a fundamentally asexual figure but I previously did not realize just HOW intent his corporate masters were on keeping Ernest from being a magnificent fuck-beast.

The IMDB Trivia for Ernest Goes to Jail contains this fascinating bit of information: “(quasi-love interest) Charlotte Sparrow was originally written to get together with Ernest at the end. Jim Varney and the writers always wanted a love interest for Ernest. Several times he mentions a wife in the early commercials. Disney, however, vetoed the notion of Ernest experiencing any type of romance or love. Disney told the writers, "He's smooth down there". The writers were crushed once they were told that Ernest had no genitalia, they felt it was like finding out there's no Santa.”

While Felix enjoys freedom and plots to rob the bank that foolishly employs his exact double, Ernest tries to escape prison through a series of comical ruses, including cross-dressing.

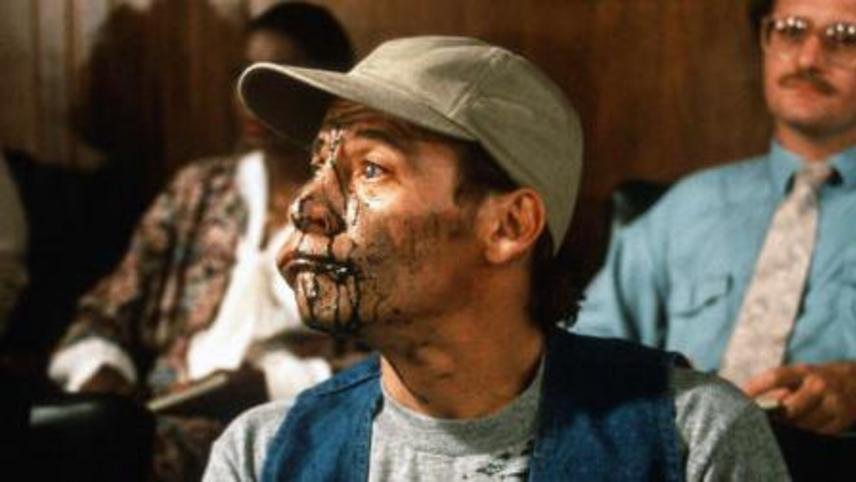

Nothing works, however, and he ends up in the electric chair. The hapless son of the South is electrocuted but instead of killing Ernest the electricity instead gives him super powers. He’s able to control electricity and also fly.

Director John Cherry apparently wanted Ernest to grow to the size of Godzilla in a climax where he squares off against Felix Nash but Disney thought that would be too expensive.

So Ernest instead FUCKING FLIES like some manner of hillbilly Superman. He even blasts off into the stratosphere at one point, seemingly to his death, only to return all charred and burnt to a crisp and conclusively defeat the bad guy.

Ernest Goes to Jail is gloriously surreal in a Hellzapoppin’/Olsen and Johnson way. Ernest builds upon his inspirations, whether in the form of the unmistakably Pee-Wee Herman-style house where our hero lives, which is full of wacky, homemade contraptions and crackpot inventions, or by having Ernest’s boss be named Oscar Pendlesmythe, a tongue-twister of a moniker that Ernest butchers in an enjoyably Jerry Lewis-like fashion.

Ernest Goes to Jail was a sizable hit but Varney’s subsequent vehicles would prove less lucrative and successful. It wouldn’t be long until Ernest’s movies began going direct to video but at the very beginning of his glorious, underrated film career, Varney was sharper and funnier than his reputation as a walking punchline would suggest.

Ernest Scared Stupid (1991)

There’s something bittersweet, even melancholy about the place 1991’s Ernest Scared Stupid holds in Ernest P. Worrell mythology. The Halloween-themed horror comedy marks the end of an era and the close of Ernest’s Golden Age.

For a handful of glorious years Disney honored the legacy of its founder and longtime leader by employing the services of Jim Varney as hillbilly hero Ernest P. Worrell in a quartet of motion picture masterpieces.

For the first time in its whole miserable “woke” existence Disney was finally responsible for something that brought people joy and made moviegoers happy: an Ernest movie.

A series of legendary collaborations ensued. Disney, through Touchstone, made movies about Ernest P. Worrell as a savvy investment, since his movies tended to be cheap and profitable, but also as a public service.

Disney gave Varney and his collaborators millions of dollars to realize his cinematic ambitions. That doesn’t sound like a lot, and generally isn’t, but it is for a guy like Varney, who was used to banging out content quickly and cheaply for an endless series of local commercial clients, it was a veritable fortune.

Disney’s millions got Varney’s vehicles theatrical releases with ad campaigns and publicity tours and reviews, albeit generally of the enthusiastically negative variety, in all the big newspapers and television shows.

Touchstone’s budgets attracted co-stars like Ernest Goes to Camp’s John Vernon and Lyle Alzado, Ernest Goes to Prison’s Charles Napier and Randall “Tex” Cobb and Ernest Scared Stupid’s Eartha Kitt.

Those might not have been the biggest names in the business but they’re all solid character actors with impressive legacies. Ernest’s early Touchstone movies took up cultural space just by virtue of being theatrically released in a way his direct-to-video cheapies could not and did not.

Alas, after Ernest Scared Stupid under-performed at the box office Touchstone turned their back on Varney. I’d like to think that they cursed themselves for eternity by doing so but they honestly seem to be doing pretty well even without lovable old Ernest P. Worrell.

Ernest would only be the star of one more theatrical vehicle, 1993’s Ernest Rides Again and then four direct to video movies.

But before Ernest’s fall from grace he first wowed children, and pretty much only children, with a Halloween-themed spook fest that is to Gen-Xers what Easy Rider was to the 1960s counter-culture: a towering masterpiece that changed film forever and defined a generation.

At the very least Ernest Scared Stupid got under our skin. It infected our individual and collective imagination with images, moments and characters that we will never forget.

Ernest Scared Stupid opens with a flurry of clips from classic horror movie monsters intercut with Ernest responding with varying degrees and fear and mortification.

It’s the essence of constructive editing, splicing together images to tell a story and create a new reality. But it’s also a testament to Varney’s magnetism that he doesn’t need gags or words or material to be funny.

Varney just needs that endlessly expressive rubber face and a level of raw charisma and sexual magnetism not seen since the early days of James Dean and Marlon Brando.

We begin with a prologue that affords Varney yet another opportunity to play someone other than Ernest P. Worrell. In this case that’s ancestor Phineas Worrell, a 19th century town elder introduced sealing a troll named Tantor inside an oak tree to contain his evil.

An enraged Tantor puts a curse on the Worrell family that every generation will be progressively dumber until the dumbest member of the family will unwittingly free the troll from his wooden prison so that he can terrorize the town anew.

We then leap forward to the present, where Ernest P. Worrell has fulfilled at least part of the troll’s prophecy by being, in the words of one of the misunderstood juvenile delinquents in Ernest Goes to Camp, dumber than a bucket of hair.

Ernest may not be the sharpest tool in the shed but he means well. He’s an overgrown third-grader with the pure heart of a child and a cerebellum full of cotton candy and pudding.

When Ernest pals around with children it doesn’t seem creepy because he seems like a contemporary and a friend more than a grown up or a responsible adult. So when bullies destroy some middle schoolers’ haunted house Ernest offers to help them out by building a tree house on the exact tree where Tantor has been imprisoned for one hundred years.

They’re fine as long as Ernest does not deliver a specific set of words that will set Tantor free to run amok but Ernest, being an idiot, can’t resist the siren song of doing the stupidest thing possible.

The denim-clad dullard recites the exact words he’s not supposed to and unleashes Tantor to wreak havoc on a new generation of children.

Ernest’s blundering upsets Francis "Old Lady" Hackmore (Eartha Kitt), a wise old woman and the apparent keeper and protector of the town’s darkest secrets. A legend like Kitt could easily sleepwalk through her role in the fourth installment in the Ernest P. Worrell saga.

The woman is a legend and an icon so it is not surprising that she instead commits one hundred percent to the role with her trademark hypnotic intensity. When it came to filling out the supporting cast in Ernest’s first four movies it was all about getting the right name as opposed to a big name.

If you’re making a slobs versus slobs camp comedy, for example, you can’t do better than John Vernon as the head bad guy and Lyle Alzado as his flunky, assuming Ted Knight is unavailable for the role, which he was, on account of being dead.

Charles Napier and Randall “Tex” Cobb are similarly perfect typecasting for the warden and convict sidekick roles in a dark yet PG and family friendly prison comedy like Ernest Goes to Jail.

Kitt has to be at the top of the list for the wise old lady role for a movie like this. Kitt goes above and beyond when she could easily get away with minimal effort. The same is true of the special effects legends who created the impressively disgusting Tantor and later a whole rampaging troll army: the Chiodo Brothers.

The geniuses behind such apogees of cinematic excellence as the stop motion animation for Large Marge in Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, Philo’s true form in UHF, the Critters and Killer Klowns from Outer Space created Tantor and his hideous monster brethren.

They worked magic on a very limited budget, creating out of rubber and sweat and imagination a troll that is pure nightmare fuel for children. Tantor steals the essence of kiddies by transforming them into wooden dolls.

This traumatized an entire generation of kids who saw Ernest Scared Stupid in the theaters and/or on home video, and could not get Tantor and his tricks out of their fertile imaginations.

Ernest Scared Stupid doesn’t need to be scary or creepy. It may be a horror comedy but it’s an Ernest movie first and foremost so audiences weren’t exactly expecting The Exorcist.

The cult horror movie proved creepier and more unnerving than expected or even desired really. That’s part of what sets it and the rest of the early Ernest movies apart. They soared over the audience’s VERY low expectations by being strange, unexpected and dark in addition to stupid.

As in his previous vehicles, Ernest talks largely for the pleasure of talking. He is forever monologuing in a way that suggests he doesn’t actually care whether anyone else is listening or paying attention. When Ernest gets into a rant here he doesn’t just change accents and dialects and personas: he changes outfits as well, alternating between an old lady get-up, a proud Roman soldier costume and of course the overalls of his beloved Walter Brennan cowpoke character.

There’s nothing children like more than Walter Brennan impersonations. In show-boating riff mode Varney suggests a redneck variation on Robin Williams’ manic stand-up.

It’s a shame Varney and Williams both died young and tragically and never worked together. They were both eternal friends of lonely children whose life’s work involved making people happy.

Williams was the more respected artist but I like to think that had Varney not died at 50, with so much left to give, while that piece of shit Matthew Perry is horribly, inexplicably still alive, he would have won an Oscar as well.

Unfortunately Varney died young and while I’ve very much enjoyed the journey through his life’s work so far something tells me that we’re about to hit a VERY rough patch now that his Disney period is officially over and his direct-to-video nadir lurks menacingly in the very near future, not unlike Tantor and his wooden dolls of death.

Ernest Rides Again (1993)

Every Golden Age has to end. Every heyday has to come to a close eventually. Nothing gold can stay.

For Jim Varney, Ernest P. Worrell’s legendary winning streak came to an abrupt end with 1993’s Ernest Rides Again, his first movie post-Touchstone and his final film to receive a major national release.

The next Ernest movie, 1994’s Ernest Goes to School, was theatrically released in just two lucky cities: Cincinnati and Louisville. Varney’s subsequent three vehicles, 1995’s Slam Dunk Ernest, 1997’s Ernest Goes to Africa and 1998’s Ernest Goes to Africa, all went direct to video.

Then Jim Varney died in 2000 at the age of fifty-one of Lung Cancer before he could bless the world with any more Ernest movies. By that point, unfortunately, the series had been in decline for a half-decade.

The problems with Ernest Rides Again begin with its title. Ernest’s Touchstone movies all had titles that told you EXACTLY what you were in for. The title of 1987’s Ernest Goes to Camp let audiences know that the commercial world’s preeminent affable idiot had made the leap to the big screen with a slobs versus snobs Summer camp movie.

1988’s Ernest Saves Christmas, meanwhile, none too subtly broadcast that Ernest’s second big cinematic vehicle was one of those holiday classics where a lovable goober keeps Christmas from being cancelled.

1990’s Ernest Goes to Jail was a lighthearted prison movie while 1991’s Ernest Scared Stupid found Ernest getting into the Halloween spirit with a delightfully traumatizing horror-comedy.

Ernest’s classic Touchstone vehicles all found the irrepressible son of the South in a clearly delineated, richly conceived cultural milieu. That unfortunately is not true of his first real flop, 1993’s Ernest Rides Again.

Ernest Rides Again’s title is maddeningly vague. It says NOTHING about the film’s contents. That might be good since the marketing wizards behind the movie inexplicably chose to focus on subjects of zero interest to Ernest’s fanbase of small child and easily amused adults like myself: academic competition, valuable artifacts and the Revolutionary War.

That’s not a terrible commercial subject for a children’s film and Ernest’s country-fried shenanigans famously failed to catch on with intelligentsia and the smart set. This may be hard to believe, but not a single Ernest movies has been deemed culturally, historically or aesthetically significant enough to qualify for preservation by the National Film Registry.

Not even Ernest Goes to Camp.

As its title frustratingly fails to suggest, Ernest Rides Again finds sweet-natured redneck Ernest P. Worrell working as a janitor at a college. In an early set-piece that promises more than the film ultimately delivers, an electric saw that Ernest is using seemingly attains sentience and develops a nasty, murderous attitude towards him.

For a few agreeably insane minutes Ernest Rides Again turns into a hillbilly version of Maximum Overdrive as the tools of Ernest’s trade turn dramatically and defiantly against him and try to wreak bloody vengeance.

Ernest is understandably both confused and terrified. “I’m not your enemy! Some of my best friends are power tools!” Ernest attempts to assure the blood-thirsty, power-mad power tool.

In Ernest’s surreal world, even inanimate objects have it in for him. Life never stops defecating explosively in Ernest’s mouth yet he never loses his positive attitude, innate sweetness or belief in the fundamental goodness of human nature.

It’s a standout physical comedy set-piece and a wonderful showcase for Varney’s prodigious gifts but it also feels an awful lot like the scene in Ernest Goes to Jail where Ernest is terrorized by metal objects that chase him up a wall and defy all laws of physics and gravity in their mad pursuit. Even at its best, Ernest Rides Again finds the filmmakers engaging in blatant self-cannibalization.

Ernest doesn’t have much going for him beyond a decidedly one-sided friendship with nerdy professor Dr. Abner Melon (Ron James). Ernest thinks of himself as Melon’s dear friend and trusted professional peer. Melon, meanwhile, sees Ernest as an annoyance he neither wants nor needs.

The central role of a geeky academic with a domineering wife and hostile professional colleagues cries out angrily for the raw, sweaty magnetism of Eddie Deezen, the big dick energy of Curtis Armstrong or the monster swag of Tim Kazurinsky.

In order for Ernest Rides Again to work as a buddy comedy you need to pair Ernest with a strong sidekick/comic foil but James leaves a charisma and humor vacuum in a lead role. Ernest is perhaps our greatest icon but journeyman Canadian stand-up comedian Ron James is, regrettably, just some guy.

When Ernest finds a mysterious old metal plate he brings it to Dr. Melon, who sees it as proof that the Crown Jewels are hidden inside a massive Revolutionary War cannon known as Goliath and what are ostensibly the Crown Jewels in England are nothing more than a fake.

Dr. Melon’s colleagues write him off as a crackpot and a conspiracy theorist for his beliefs but Ernest believes in him AND his crazy ideas, just as he unfortunately would probably believe conspiracy theories involving QAnon if he were making movies today.

I can only imagine how disturbing a contemporary Ernest P. Worrell movie would be with its no longer harmless hero excitingly telling his friend Verne about some things he just learned on his computer about celebrities and their insatiable addiction to Adrenochrome and how Joe Biden is actually a clone.

So it is perhaps a good thing that fate spared us 2021’s Ernest Goes Full-On QAnon.

Dr. Melon’s ideas are kooky and off the wall but they’re not treasonous or dangerous. He is nevertheless an object of sneering derision at the college where he teaches before Ernest’s discoveries suggest that the nutty professor was right all along.

The low-wattage comedy team of Ernest P. Worrell and Dr. Abner Melon finds the Crown Jewels hidden inside an antiquated weapon. Feverish competition ensues as the daffy duo tries to stay one step ahead of both a big time professor who wants to get his hands on the impossibly valuable artifacts and the British government, which wants to suppress news that the real Crown Jewels have been hidden inside a cannon in the United States for hundreds of years, not unlike how the Biden administration is trying to suppress news that all of the top athletes are dying horrible deaths due to receiving to the COVID vaccine.

That’s way too much plot for an Ernest movie. It’s also way too stupid a premise for an Ernest movie yet also somehow not stupid enough.

I chuckled a few times during Ernest Rides Again. It’s intermittently amusing but unlike the vehicles that preceded it, I would not say that it’s funny. I also would not recommend it unconditionally to literally everyone in the world the way I would Ernest’s previous masterworks of cinema.

Ernest Rides Again closes by teasing its hero’s next adventure, Ernest Goes to School, but his words inspired mild dread instead of feverish excitement.

It pains me to write this, but after Ernest Rides Again, I know no longer know what Ernest means. That beautiful emotional and spiritual connection has been lost.

And, if my fuzzy memories of Slam Dunk Ernest are any indication, it’s only going to get worse, and more racially problematic from here, and that’s only partially because Ernest Goes to Africa lies ahead.

Unlike Ernest Rides Again, Ernest Goes to Africa’s title conveys its contents all too well. If it’s anything like pretty much every American comedy set in Africa, ever, it will be clueless at best and extremely racist at worst.

Ernest Goes to School (1994)

J0th, 1994 was a magical day for the good people of Cincinnati, Ohio and Louisville, Kentucky. No one could possibly have known at the time, other than anyone familiar with the series’ dwindling box-office grosses, that that fateful day would mark the very final time a fella would be able to say to his gal, “What say you and me have a kissing date in the balcony of the theater showing the newest Ernest P. Worrell movie? I’ll buy popcorn and soda and we’ll smooch up a storm!” without seeming like a lunatic.

Do you think the folks in attendance at those magical final showings had any idea how lucky they were? Could they possibly have grasped the historic importance of their actions?

The rest of the world wouldn’t get to experience Ernest Goes to School until December 14th of the same year, when the Jim Varney vehicle was dumped onto home video.

Ernest Goes to School would be the last Ernest movie to receive even the most modest of theatrical releases. The last three Ernest movies, Slam Dunk Ernest, Ernest Joins the Army and Ernest Goes to Africa would go direct to video.

Some say our nation, built as it was upon the wholesome twin pillars of slavery and the genocide of indigenous people, lost its innocence when JFK was assassinated. Others argue that happened on 9/11. I say that our nation truly lost its innocence when some sick, power-mad fuck decided that Jim Varney portraying the role of good-natured bumpkin Ernest P. Worrell somehow did not merit at the very least a robust theatrical release with a healthy advertising campaign and worldwide promotional tour.

Some say Jim Varney died from Lung Cancer after decades as a heavy smoker. I say that he died of a broken heart after his beloved public, whom he only wanted to entertain, turned their back on him by refusing to support his movies with their money and passion.

Rumor has it Varney’s final words were a heartbroken “Why hath forsaken me?” delivered to moviegoers who had turned into movie non-goers somewhere around Ernest Rides Again.

But before Ernest became a purely direct-to-video phenomenon he put out a movie that might as well have skipped the theaters in 1994’s Ernest Goes to School.

The oddly engaging mash-up of Flowers for Algernon and Billy Madison finds Varney’s denim-clad practitioner of the janitorial arts toiling happily as a fix-it man at Chickasaw Falls High School, home of the Fighting Muskrats.

An evil superintendent wants to find an excuse to shut the school down so that it can be consolidated with a nearby educational institution so he seizes upon a rule dictating that all employees must be high school graduates or face termination.

Throughout the Ernest franchise there are moments when the bumbling hero talks like an idiot-savant whose doltish persona masks a streak of grandiosity and verbosity. In Ernest Goes to School, for example, Ernest takes forever to do a math problem yet exhibits an exhaustive knowledge of growing conditions for citrus in the American South. And when he’s threatened with termination if he doesn’t get his diploma Ernest turns into a human dictionary and rattles off a bunch of synonyms for getting fired.

In Ernest Rides Again Ernest tells a buddy amazed that he survived a pratfall that the key to his seeming immortality lie in being pretty much a cartoon character. Like a cartoon character, Ernest’s intelligence is elastic. He can be as smart or as stupid as any scene needs him to be.

That’s particularly true of Ernest Goes to School, where the plot hinges on his intelligence and sophistication fluctuating wildly from one moment to the next.

Ernest is worried about losing his job so he re-enrolls in high school as an adult. On his first day he doesn’t know what to do or where to go until the crowd dissipates, leaving only a Clint Eastwood-like cowboy on a horse who tells him where to go and also that he needs a hall pass.

We never see this horseman again. He serves no purpose within the narrative. It’s just the kind of weird, borderline avant-garde gag you see even in lesser Ernest movies.

Varney’s post-Touchstone output shares with his Disney Golden Age a fantastical conception of the material world as being in violent conflict with Ernest. In an early physical comedy set-piece, Ernest’s earnest attempts to fix faucets and doohickeys and whatnot invariably leads to inanimate objects rising up again Ernest with great anger as they try to take the poor man’s life.

Ernest’s attempts to fit in at school are at first a distinct failure. A bully pulls the old “setting the new guy’s hat on fire” gag. An embarrassed Ernest accidentally steps hard on a comically oversized tube of glue that splatters all over his teacher’s body in a way that makes it look like an elephant has just ejaculated lustily on his torso.

The universe has it in for Ernest. Bullies bully him. Snooty superintendents try to get him fired. Machines are perpetually trying to kill him. Critics don’t understand him or his genius. Neither do intellectuals. Disney gave him the old heave ho.

The man could use a break. He gets one when a pair of mad scientists who inexplicably operate out of a locker at the school use him as a guinea pig to test a new machine to make people smarter.

In a Charly-like development that did not, sadly, result in a Charly-like Academy Award for Best Actor for Varney, the machine works like gangbusters. The simple man goes from zero to intellectual hero, from lowbrow to highbrow, from slob to snob, from good-natured goober to human super-computer.

The transformation is visual as well as intellectual. He inexplicably starts wearing glasses as well as a tie and a dress shirt instead of his signature grey tee. They never explain WHY Ernest suddenly needs glasses but he’s now not just smart but super smart and smart people all wear glasses. At least all the Poindexters do.

The Smart Ernest is a bit of an insufferable know it all. He’s a William F. Buckley type intellectual who broadcasts his superiority over simple folk in a most non-Ernest fashion.

He is a genius with an Einstein-level intellect who can play every instrument and has an encyclopedic knowledge of the works of John Philip Sousa.

This comes in handy, because the pre-transformation Ernest developed a schoolboy crush, or rather a school-man crush on Ms. Flugal (Corrine Koslo), his music teacher.

Ernest Goes to School flies in the face of convention in giving Ernest a love interest who is completely average-looking, a plain church secretary type in dowdy cardigans and high-collared shirts.

I’m so used to every female love interest being, at the very least, extremely attractive, that it is legitimately a little jarring to see Varney partnered with someone who looks like a regular person and not an actress.

The mad scientists are overjoyed with their patient’s progress. When he asks if the brain-juicing machine will help him pass a math test, a scientist giddily quips, “Pass a test? Try rewriting the Theory of Relativity!” to which he earnestly insists, “Well, if you think it really needs it!”

The line and Varney’s aw-shucks delivery are both hilarious, as is the idea of Super-Smart Earnest re-writing the Theory of Relativity in order to improve it.

Ernest Goes to School’s idiot plot involves the super-smart Ernest helping save the school by transforming its football team into champions and its marching band into virtuosos.

It is established repeatedly that the school’s salvation lies in athletic victory, not in anything as nerdy or irrelevant as education or community service. No, it all comes down to winning the big game and pulling off a knockout halftime show.

The intelligence machine only makes Ernest brilliant for limited amounts of time. Then he goes back to being a dumbass. He’s Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hillbilly, with a tendency to begin activities as the smartest version of himself, only to revert to his goofball self at the worst moment.

In Educated Sophisticate mode, for example, Ernest tells the band he has been leading with supreme confidence to look at him and follow his lead if they’re confused or need direction.

This inevitably leads to catastrophe when things get all screwy and Ernest ends up with his head inside a tuba, greatly constricting both his vision and his range of movement. The band obliviously mimics Ernest’s every blunder and misstep as instructed in flagrant violation of common sense and solid judgment.

Watching the high school band members make idiots of themselves in imitation of Ernest engendered a sort of guilty double laughter for me. I laughed at how stupid and groaningly predictable the gag is but I also laughed at myself for being stupid enough to find something like that laugh out loud funny.

I don’t want to be overly critical, but if I were one of those YouTubers who perform an invaluable service in scrupulously documenting every single way in which a silly Hollywood movie is not EXACTLY like real life I could spend four or five hours pointing out the implausibilities of the climactic football game.

For starters, I’m pretty sure you’re not allowed to play wearing only a denim vest and baseball hat for protection. And a play called “The Cupid” where a pretty girl on one team tricks a member of the other team into falling in love with her solely so that he will give her the football during game-time as a token of his infatuation seems like it would violate at least eight or nine different rules.

I never thought I would write these words, dear reader, but the Ernest movie I just watched and am writing about was actually pretty stupid but I chuckled a fair amount and enjoyed the ridiculousness of the whole affair, as well as its casual surrealism.

I enjoy the character so even when he’s not in peak form I still end up having fun.

Will that hold true of Slam Dunk Ernest? I honestly have no idea. It’s the only Ernest movie I’ve seen I remember flat-out disliking but I’m a lot more pro-Ernest these days so it’ll be interesting if it will frustrate and appall me a second time or if it will join all of the others as movies I have a distinct fondness for, regardless of their quality, or lack thereof.

Slam Dunk Ernest (1995)

We are deep into our exhaustive exploration of the films of Ernest P. Worrell. After this piece only two movies remain, both shot in South Africa and released direct-to-video with a star whose seemingly limitless energy and stamina were drained by the lung cancer that would soon take his life.

We’re seven films into this most worthwhile and important of cinematic journeys yet the deeply unfortunate 1995 fantasy sports comedy Slam Dunk Ernest marks a beginning for me as well, and not a happy one.

That’s because I somehow made it forty-two years, including decades as a full-time pop culture writer who specializes in lowbrow, widely mocked and derided entertainment, without seeing an Ernest P. Worrell movie before I watched Slam Dunk Ernest for my discontinued column Control Nathan Rabin.

Why? I don’t know. It’s possible that I thought that they looked dumb or bad. That’s generally not a deterrent for me but for whatever reason, it’s taken me forty-six years to finally get around to experiencing all of these classic pieces of Americana.

I was not impressed by Slam Dunk Ernest! I was REALLY not impressed! But that was before I became an Ernest fan and chose to devote at least a few months to watching and writing about all of his vehicles.

I was a total neophyte the last time I watched Slam Dunk Ernest. I’m nothing short of an Ernestvangelist these days. I come not to bury Ernest P. Worrell but to praise him. I’ve seen the light. I now know what Ernest means.

Would my newfound affection for all things Ernest lead me to see Slam Dunk Ernest in a new, more flattering light? Would I find things to love about it where it previously left me cold? Or would it remain the first out and out dud in Ernest’s underrated and misunderstood filmography?

Hope springs eternal when you are a pop culture writer but Slam Dunk Ernest stubbornly refused to improve upon a second viewing. It remains a bewilderingly misguided piece of lowbrow entertainment, particularly in terms of its racial politics and the weirdly central role race plays in it.

In Slam Dunk Ernest Jim Varney once again plays janitor Ernest P. Worrell but here he’s part of a janitorial team called The Clean Sweep otherwise made up exclusively of NBA-caliber black athletes who live to compete in a league made up of less suspiciously, preternaturally gifted teams.

Ernest wants to roll with the hoopsters but they all think he’s too white and nerdy. He’s just too white 'n' nerdy, really, really white 'n' nerdy. The good-natured goober has all the enthusiasm in the world but unlike his African-American coworkers, he’s not naturally gifted at basketball.

At best, Varney’s cornpone creation manages the tricky feat of being simultaneously likable and comically annoying as well as poignant and fundamentally sympathetic.

Ernest P. Worrell is all of us. We are all Ernest P. Worrell. Unfortunately the off-brand Ernest P. Worrell here is pathetic and abused where he should be poignant and resilient and weirdly unlikable even when he’s not supposed to be. In Slam Dunk Ernest, the titular man of the people is a sad sack whose tragic plight inspires mostly pity.

He’ll do anything to fit in but his disconcertingly business and success-minded colleagues treat him with disconcerting callousness. They call him a cracker and a redneck. They pour lemonade on his head. They beat him up. They berate him.

This coldness and casual cruelty has a boomerang effect that renders the other main characters in the film unlikable as well as Ernest. Ernest’s teammates are a bunch of jive-talking jerks who bully Ernest because they can and because this incarnation of the character is, honestly, a little annoying.

I never thought I would write these heretical words but Ernst comes off as a bit of an idiot here and is, to be brutally candid, not hilarious either.

Ernest’s dreams of basketball greatness seem doomed to go unrealized until the Arc-Angel of Basketball (Kareem-Abdul Jabbar) gives him a magical pair of 250 dollar anthropomorphic shoes that grant him superhuman abilities.

Ernest goes from zero to hero overnight, from habitually maligned bench-warmer to NBA contender and he owes it all to shoes that allow him to do things that literally no other human being has ever done since the beginning of time, like leap twenty five feet in the air and stay there for forty seconds.

Slam Dunk Ernest suffers from an unmistakable element of self-cannibalization. It is, after all, the second consecutive Ernest movie about an amiable dolt who acquires superhuman abilities and turns into an arrogant, narcissistic jerk.

In Ernest Goes to School Ernest gets hooked up to a brain enhancement machine that made him super smart and a football wiz. In Slam Dunk Ernest he gets magical shoes from an angel and becomes the greatest athlete the world has ever known.

Ernest is an inherently likable character yet Ernest Goes to School and Slam Dunk Ernest are nevertheless in a perverse hurry to turn him into an arrogant asshole who thinks the world revolves around him and his greatness.

Ah, but Ernest isn’t just the world’s greatest athlete. He’s also a pawn in an eternal game of good versus evil. God takes an interest in Ernest but so does Mr. Zamiel Moloch (Jay Brazeau), AKA the Devil.

The Great Deceiver corrupts innocent Ernest by giving him the power and status that he has longed for his entire life and transforms Ernest’s crush Miss Erma Terradiddle (Stevie Vallance) from a cheerful geek into a tawdry seductress.

In a fascinatingly out of place subplot that takes up way too much time when it should have been left on the cutting room floor, Barry Worth (Cylk Cozart), the leader of the Clean Sweep basketball team and the owner of the business, must deal with his impressionable son Quincy’s disappointment that his father has a blue collar job instead of doing something more glamorous and high-paying, like being an NBA player.

This subplot is played entirely straight. It’s a weirdly earnest blast of A Raisin in the Sun in what is otherwise a goofy fantasy about a hillbilly whose ability to literally fly through the air like a majestic bird makes him a contender for NBA stardom but not, inexplicably, a subject of serious scientific inquiry to determine what makes Ernest different from everyone who can’t fly.

Mr. Zamiel Moloch wants to corrupt Quincy through Ernest and the magical shoes but God is good and Ernest eventually learns his lesson and forsakes Satanic basketball magic in favor of good old fashioned hard work.

Slam Dunk Ernest is undoubtedly well-intentioned but its message that black children should stay in school so that they don’t end up being a janitor like their dad is condescending at best and kind of racist at worst.

Slam Dunk Ernest contains way more Ebonics than is at all proper or appropriate for a redneck hero like Ernest P. Worrell. It’s too silly and too sentimental and largely devoid of laughs and memorable gags or set-pieces.

Ernest P. Worrell’s seventh outing as a leading man is quite poor and I say that as a fan. They can’t all be winners, and Slam Dunk Ernest, alas, is a real loser.

Ernest Goes to Africa (1997)

This is just getting sad.

It’s heartbreaking, is what it is. The story of Ernest and film began in triumph, with a hayseed savant of the local commercial universe scoring boffo box-office for his 1987 starring debut, Ernest Goes to Camp.

By the time Ernest Goes to Africa was dumped direct to video in 1997 things had taken quite a turn. He was no longer working with Disney. His movies were no longer released theatrically or reviewed widely. The budgets shrank as he went from filming in Nashville to Canada to South Africa, where he shot his final two vehicles back to back.

When Varney starred in Ernest Goes to Africa he had been playing Ernest for seventeen LONG years and been making Ernest movies for a solid decade.

As I have written before, slapstick and physical comedy are a young man’s game. When a man in his twenties or thirties executes a pratfall it’s funny. When a man in his fifties falls down it’s just sad. You worry about the poor man’s health. What if he broke a bone or sprained something? You feel bad for him. It’s just not dignified.

In Ernest Goes to Africa Jim Varney is like a legendary baseball player who insists on playing well into his forties even when it’s obvious to everyone that he’s lost a step or two or three and retirement beckons.

One of the many things that impressed me about Varney’s early films is Varney’s potent combination of energy and precision.

By 1997, however, decades of chain smoking and hard living were starting to catch up with Varney. He was only a few years away from dying young of lung cancer and had begun to look his age.

Varney probably should have stopped making Ernest movies after Ernest Goes to School but it’s hard to turn down money and work, even of the most regrettable variety and Ernest Goes to Africa is a deeply unfortunate enterprise.

At the risk of stating the obvious, Ernest NEVER should have gone to Africa. It’s a terrible idea for any number of reasons, most having to do with race and racism.

During the Touchstone years Disney perversely insisted that Ernest be as sexless and devoid of genitalia as a Ken doll. They couldn’t handle Varney’s raw sexuality and big dick energy so they castrated him creatively.

In Ernest Goes to Africa Ernest has a love interest who scores nearly as much screen time as he does but her presence suggests that Disney was right.

Linda Kash, who appeared in two previous Ernest adventures in different roles, plays female lead Rene Loomis. She’s a small town waitress who longs to escape her humdrum little world for a life of adventure and intrigue.

Ernest, who honestly comes off as a bit of an incel here, nurses a desperate crush on the food-slinging dreamer but she rejects him for not being worldly or exciting enough, for being a quintessential “Nice Guy” instead of a studly, womanizing “Chad.”

yeah, no shit. This is not safe to watch with anyone.

Our hillbilly hero unfortunately cannot take no for an answer so he goes to a flea market to buy her a present and, through complications too stupid to go into, ends up somehow stumbling across two massive diamonds collectively known as Eyes of Igoli, which are sacred to the Sinkatutu tribe of Africa.

Ernest Goes to Africa offers audiences an Indiana Jones-style adventure with all of the racism, colonialism and ancient stereotypes and none of the adventure or fun. What Ernest Goes to Africa does have is a level of violence and brutality wildly inappropriate for a movie pitched exclusively to small, stupid children.

It’s filled with knives and deadly snakes and crude caricatures of sweaty, desperate criminality squaring off against one another in a pointless quest for the MacGuffin at the film’s core.

Ernest Goes to Africa depicts its setting as a violent realm of barbarism and brutality populated by heartless criminals. I’m talking about sinister figures out of the imperialist imagination like Bazoo, a dark skinned African enforcer who takes great delight in terrorizing people on behalf of a white boss who treats him with undisguised contempt.

Bazoo really wants to physically and/or sexually assault Rene but this is a PG rated Ernest movie for the whole family so there are clear intimations of sexual violence but never anything explicit.

You know, for kids!

Life is cheap and death is everywhere here. That’s a strange, unfortunate choice for a movie about a formerly lovable and previously amusing country-fried goober.

An oblivious Ernest turns the diamonds everyone wants into a yo-yo without realizing that the stones he bought for a dollar are priceless treasures.

Ernest is dumb enough to leave his name and whereabouts at the flea market stall where he unknowingly bought the Eyes of Igoli from a sleeping merchant.

Shortly after Rene rejects Ernest for being “just a small town ordinary schmo” they’re kidnapped and taken to Africa by bad guys convinced that they know the location of the sought after jewels.

For reasons I cannot begin to understand, in the 1980s and 1990s broad comedies targeted at kids and family audiences were inexplicably obsessed with the international black market for precious jewels and filled with diamond smuggling subplots no one could possibly care about.

Ernest Goes to Africa is sadly representative of this curious breed although, to be fair, making this Ernest adventure diamond smuggling-themed does facilitate much of the racism and violence that are its peculiar raison d’etre.

Ernest and his would-be girlfriend end up pawns in a high stakes war between vicious smuggler Mr. Thompson (Jamie Bartlett), Bazoo’s rage-poisoned boss, and Prince Kazim (Robert Whitehead), a sleazy royal obsessed with tracking down the Eyes of Egoli.

To find Rene Ernest slathers on darkening make-up, makes a turban out of what appears to be a towel, borrows Peter Sellers’ accent from The Party and does brown face as “Hey-Yu.”

I had a strong hunch that Ernest Goes to Africa would prominently involve either brown face or blackface despite it being released in 1997 and not 1927.

That’s the implicit threat of the film’s title and premise. Since Ernest Goes to Africa is every bit as bad, racist and problematic as you think it would be, if not worse, it most assuredly does includes unconscionable and unforgivable, not to mention un-funny brownface when Ernest darkens up to portray a sniveling sycophant derided as a filthy urchin by the criminal scum he’s trying to impress.

The subterfuge and role-playing continues when Ernest resurrects his gloomy, hectoring Aunt Nelda character before Ernest goes undercover as a harem girl in Prince Kazim’s harem in a set-piece that seems to last several days, if not months.

Ernest tries to communicate with a South African tribe through a crude approximation of 1970s jive talk, addressing them as “homies” and asking “What is happening?” They initially propose ripping his arms off and chopping off his legs before smacking him on the head with a stick, knocking him unconscious before being inexplicably won over by his hillbilly shtick.

In a running gag that limps, Ernest is forever talking about turning on the old “Worrell charm” when he’s never been less charming or appealing.

Ernest Goes to Africa ends with its female romantic lead rejecting its male romantic lead in favor of a boring nobody whose only real strength is that he’s not Ernest P. Worrell. It’s a perverse anti-climax that seems to acknowledge that its hero has never been less appealing.

Ernest Goes to Africa isn’t just sub-theatrical quality. It’s sub-direct-to-video as well. When people think of Ernest movies as dumb and embarrassing, unfunny and vulgar, this is what they’re talking about.

I never thought I would write these word, but this African-themed, late-period Ernest movie is more than quite poor: it’s an abomination.

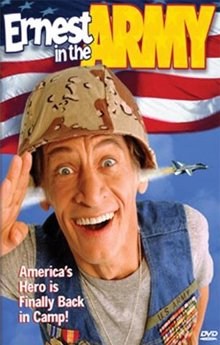

Ernest in the Army (1998)

Every saga has an ending. Take The Simpsons. That will probably end at some point. Possibly. And the best part of that show’s glorious run is that it has maintained the same impossibly high level of quality over thirty four equally transcendent seasons.

The same, unfortunately, cannot be said of the Ernest P. Worrell movies. The beloved and prolific TV pitchman roared out of the gate with four timeless masterpieces in Ernest Goes to Camp, Ernest Saves Christmas, Ernest Goes to Jail and Ernest Scared Stupid but as is so often the case with great artists who have used their voices to say something profound about the human condition, the end was not pretty.

1995’s bewildering Slam Dunk Ernest found the series taking a hard turn into oblivious racism before Ernest Goes to Africa inexplicably and regrettably added brown face to the mix while amping up the racism considerably.

Just about the nicest thing that can be said about 1998’s Ernst in the Army, the final film in the Ernest series, is that it’s not quite as terrible or racist as the stinkers that precede it but it still manages to be awful and also fairly racist in its own right.

Ernest in the Army finds Ernest signing up to become just another cog in the imperialist American war machine out of an innocent, child-like desire to drive large vehicles.

The film was apparently a personal project for John R. Cherry III, who created and refined the character of Ernest P. Worrell with Varney, first in a series of local and national television commercials and later in television and film.

The two defining experiences of Cherry’s life were serving in Vietnam as a young man and shepherding the Ernest series as an adult. That means that there is a fairly good chance that the man who created Ernest has probably killed somebody, possibly even within the context of warfare.

War changes people. It forces them to confront death and their own mortality, as well as man’s inhumanity to man. Cherry III’s experiences in Nam inform every stupid pratfall here although the conflict in the film is more overtly modeled on the Iraq War.

Cherry III apparently watched news of gassings and Scud attacks and dead children and thought that that would be a fun playground for Ernest P. Worrell to frolic in.

In his God-like prime, Jim Varney was a comedy machine. He was a fast and meticulous virtuoso whose photographic memory allowed him to memorize and rattle off reams and reams of verbose dialogue at a machine gun clip.

But lung cancer and years of hard living took a toll on the performer. By the time Ernest Goes to Africa and Ernest in the Army were filmed back to back in South Africa and then dumped direct to video, Ernest’s energy had begun to flag and he was nowhere near as precise as he once was.

There’s an early scene, for example, where Ernest is riding around on his belly on a motorized vehicle while picking up golf balls at a driving range that is filmed in long shots with dialogue that was clearly added afterwards.

In his younger days, Varney would have no problem pulling off a scene like that but here “Ernest” is clearly played by a stunt double while his words are clearly the product of an ADR session.

So it is perhaps not surprising that the first twenty minutes or so of Ernest in the Army are shockingly and disconcertingly Ernest-light. Then again, the filmmakers have a LOT of plot to set up and way too many characters and conflicts to introduce.

Ernest in the Army, is, after all, about an international conflict involving the United States reserves, U.N Peacekeeping forces and President for Life Almar Habib Tufuti (Ivan Lucas), the villainous ruler of the fictional country of Aziria.

President for Life Tufuti is Ernest in the Army’s hammy take on Saddam Hussein, who was the villain du jour when the film was written in 1993. Why did it take the film five years to hit undiscriminating video store shelves? Probably because Cherry III spent a solid half decade painstakingly perfecting a magnum opus he was convinced would be his masterpiece, the one that they would remember him for.

Ernest in the Army would be Cherry III’s ultimate statement. Cherry III even cast himself in a sizable supporting role as Ernest’s buddy, apparently because he couldn’t find anyone to do a convincing Southern accent in South Africa.

In a move at once off-brand and kind of sweet, Cherry III himself delivers Ernest’s catchphrase, “Know what I mean?” more than once. Cherry III is not much of an actor but all his role really calls for is a Southern drawl and easy rapport with Jim Varney and those were both in his tiny wheelhouse as a thespian.

Ernest in the Army has so much non-Ernest business to get through that it has a newsman delivering exposition on an CNN-like news station that figures prominently in the plot AND perversely somber narration from a resident of Karifistan who is rotting in a prison after his wife was murdered, leaving his son Ben-Ali (Christo Davids) to run the streets a lost boy, with no one but an American goober to keep him from certain death.

In opening narration that is impressively unfunny, Ben-Ali’s dad gloomily states, “Once again, history spewed forth a wave of aggression that swept over the land and everything in its path was crushed beneath the treads of its ambition. There was little to stop evil’s triumphant march. So the beast lured the eagle by devouring the defenseless and an orphan child wept, praying, hoping, looking for a liberator of his land and his future.”

I just want to reiterate that those are all actual words that appear in an Ernest movie. Ernest in the Army takes its white savior narrative VERY seriously. White savior narratives are particularly problematic when the savior in question is Ernest P. Worrell, a famous dullard.

Ernest’s desire to drive big trucks leads him to enroll in the Reserves, confident that he won’t be called upon to do any actual fighting or be a real soldier. So you can only imagine how mortified he is to discover that his unit is being shipped out to the fictional Arab nation of Karifistan to assist with a U.N Peacekeeping unit by the malevolent Colonel Bradley Pierre Gullet (David Muller).

Unsurprisingly, the aggressively non-woke Ernest in the Army depicts the U.N in an only slightly more positive light than it does its bargain-basement Saddam Hussein.

Colonel Gullet sells out the U.N for cold hard cash and, in what disconcertingly, is not the only attempted sexual assault in the Ernest series (Ernest Goes to Jail has one as well), tries to force himself on Cindy Swanson (Hayley Tyson), an American journalist Ernest has a huge crush on who passed herself off as a soldier so that she can report on the war and is quickly kidnapped alongside Colonel Gullet and held hostage by President for Life Tufuti.

Ernest does not make a smooth transition to armed combat. In fact, he’s a bit of a buffoon. He is, to be honest, a real numbskull, which is on brand, obviously, but I’ve always liked it when the series would hint that Ernest was actually something of an idiot-savant with unexpected knowledge and areas of expertise to go along with all the jokes about him being dumb even for an American.

Our hero is first scammed by Ben-Ali before he saves the poor boy’s life, earning his eternal loyalty in the process. For, you see, Ernest is the fulfillment of the prophecy about the great American warrior saving the people of Karifistan from the evils of Tufuti.

Ernest more or less single-handedly defeats Tufuti’s evil minions and without using a gun, either. He’s a fool who bumbles his way into literally unbelievable heroism.

The cornpone icon saves EVERYBODY. He saves the boy, who is then reunited with his father, and his reporter crush and also the people of Karifistan.

In an act of mild sadism, Touchstone, which put out the first four Ernest movies, insisted on the character being not just asexual but devoid of genitalia, as smooth as a Ken doll below the belt.

You’d think that Ernest would go hog wild like an Amish kid on Rumspringa once he escaped Disney’s shackles and grim moralism and put out a vehicle called Ernest Gets His Fuck On, Ernest Does the Kama Sutra or Ernest Does Everybody.

That, sadly, was not to be. Ernest has semi-love interests in some of his latter vehicles, but none are at all satisfying.

That’s true here as well. Cindy rewards Ernest for SAVING HER LIFE with a chaste, closed mouth kiss on the lips.

It’s tame stuff, dry PG semi-smooching but Ernest is so anxious that his dried lips peel off during the clinch. Instead of being so turned on that she begs Ernest to fuck her, the ambitious journalist instead storms away in disgust.

Ernest follows after her like a lost puppy and begs for another chance but whatever attraction she might have felt towards the bumbling hero has mutated almost instantly into full-on revulsion.

It’s an insulting, undignified way to end the Ernest saga that’s followed, oddly enough, by an excessively flattering, hagiographic conclusion.