Harold Ramis' Directorial Career Got Off to an Iconic Start With Caddyshack and Lurched to a Close with Year One

With the exception of someone like Christopher Guest, and filmmaking teams, few filmmakers are as intimately associated with the art of collaboration as Harold Ramis. Ramis is best known for his collaborations with Bill Murray, which ended prematurely after Murray stopped working with Ramis after Groundhog Day for some cryptic, unknown reason. They didn’t make that many movies together, yet Ramis and Murray nevertheless represent one of the most fruitful, important and influential partnerships in American comedy. And if you’re going to prematurely end something, Groundhog Day, one of the few perfect movies in existence, as well as one of the greatest films ever made, is a hell of a note to go out on.

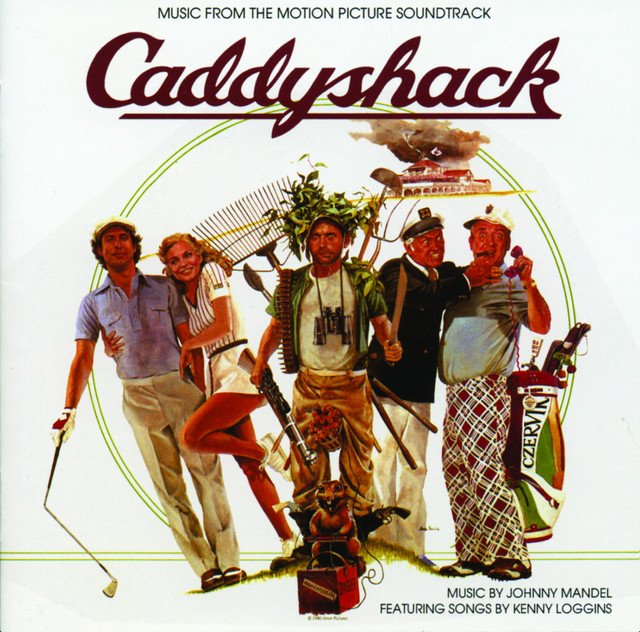

Ramis co-wrote Meatballs for Murray and then co-wrote and made his directorial debut with 1980’s Caddyshack, one of the best-loved American comedies of the past fifty years, if not necessarily one of the best. The movie is a sloppy, National Lampoon-style slobs versus snobs crowd-pleaser very self-consciously in the sneering, irreverent mold of Animal House. But due to a singular combination of elements, including, but not limited to, Kenny Loggins’ instantly iconic soundtrack songs and a gopher puppet that was brought in at the last minute to give this mess a little structure, this messy stoner comedy became something far greater than the sum of its remarkable parts, while somehow also seeming like not much of anything at all.

Caddyshack had Ramis in the director’s chair. Ramis also cowrote the script with Brian-Doyle Murray (who also quietly steals scenes in one of his first big onscreen roles) and Douglas Kenney, the troubled National Lampoon bigwig who plunged to his death the same year the film hit theaters. Even at the very beginning of his career as a director, Ramis was already singularly gifted at getting the most out of his stars. Nobody got more out of Rodney Dangerfield or Bill Murray than Ramis. Both men could be lost without Ramis’ sure hand. For proof, check out any of Dangerfield’s post-Back To School vehicles (or don’t, life is short).

Caddyshack has a bit of a bifurcated reputation. On one hand, it’s a frat boy, bro, jock, golfing classic each new generation of dudes and guys are expected to see and re-watch and worship as a sacred core text of the Church of Bill Murray. On another, it’s the kind of endlessly second-guessed, rickety pop ephemera that is susceptible to the, “Eh, this thing everyone knows and most people really like is supposed to be great. But is it that great? Maybe not” treatment, particularly on websites hungry for clicks.

“Is (Widely beloved generational touchstone) Really All That Great? Uh, We Think Not!” is one of the trustiest outrage-clickbait formulas around, and one guaranteed to draw big traffic both of the “Yes! Finally! Someone with the courage to admit the truth that that thing we’ve always been told is so great (Star Wars, The Beatles, what have you) isn’t actually that great! Thank you!” and “What? This timeless work of incontrovertibly brilliant art will be around long after your detestable hive of hipsters is dead and gone” variety.

Another, even more infuriating version of this cynical chestnut involves having a 20 year old (or so) intern watch some revered classic so they can write a sassy, in-the-moment takedown of, say, Citizen Kane for being about some weird old dumb thing called newspapers and not featuring a singe emoji.

An obnoxiously over-read think piece could certainly be written about how Caddyshack isn’t even that good of a movie and you only think it is because your older cousin who you thought was so cool had it on VHS and kept quoting it and at that age you didn’t realize at that age what a huge jerk Chevy Chase is supposed to be.

There is no objective truth about movies. It’s not an either/or proposition. Caddyshack is both a timeless and important comedy classic revered by multiple generations of comedy buffs and people with terrible, incredibly broad senses of humor alike and a stoned, shambling, shapeless mess elevated to classic status through some combination of nostalgia, intoxication and selective memory.

It does not hurt the film’s reputation that when people think of it, they invariably remember Bill Murray or Rodney Dangerfield or Chevy Chase at the height of their powers, and not the scenes involving the blandly nondescript teen caddy angling for that big scholarship. Sadly but not surprisingly, this is even true of Michael O’Keefe, to the point where he’s pleasantly surprised when he catches Caddyshack on television and re-discovers that he actually plays a big role in it.

O’Keefe stars as Danny Noonan, the film’s juvenile lead, a blue-collar kid in a world of wealth and privilege and an audience surrogate so bland that there’s absolutely nothing keeping the audience from identifying with him. In that respect, his lack of star power almost becomes an asset. O’Keefe doesn’t need to be funny; besides, it’s not like he’s going to steal scenes from Chevy Chase at his best, when he was the closest thing comedy had to a golden god, a stoner Cary Grant, or from any of the other big names or big personalities in the cast

It ultimately does not matter that from a storytelling standpoint, Caddyshack is a mess, an assemblage of vignettes and stand-alone set-pieces loosely tied together with demented groundskeeper Carl Spackler’s (Bill Murray) quest to kill a wily gopher and the yin and yang, new money Jew versus old-money WASP chemistry between Ted Knight and Rodney Dangerfield.

No, what matters is that these weird, mercurial, combustible elements found the perfect comic alchemist in Ramis, who added just enough structure to make this feel at least mostly like an actual movie, and not just a collection of some of the greatest deleted scenes ever assembled.

Ramis understood that the key to corralling this craziness lie in encouraging his cast to be the best possible versions of themselves, comedically. For Chase, that meant being as charming and appealing onscreen as he is famously detestable in real life. For Knight, it meant inhabiting the ultimate snob, being perpetually apoplectic about the hijinks and shenanigans he is forced to contend with. For Rodney Dangerfield, that meant being Rodney Dangerfield to the Nth degree, a liberating tornado of righteous vulgarity. He’s Groucho antagonizing a world of uppity Margaret Dumonts. For Murray, that meant playing the dim-witted groundskeeper as something of an accidental genius, a filthy, sideways-talking idiot savant who is alternately borderline feral in his grossness and capable of surprising moments of insight and eloquence. It’s as if the moments the cameras came on Murray attained total comic consciousness, that he ascended to a higher state of hilarity. He did not even have to wait until he was on his deathbed for it, which is nice.

Considering the place Caddyshack occupies in contemporary comedy, it can be hard to believe that the film underperformed commercially, particularly when compared to Animal House, which Ramis co-wrote. But its cult spread and spread and spread to the point where it stopped being a cult at all. This silly little goof by, for, and about stoned smartasses would go on to cast a long shadow over Ramis’ career, even when he was capable of grown-up, immaculately crafted perfection with Groundhog Day.

In that respect Ramis’ final film, Year One, represented a step back in more ways than one. Ramis grew tremendously as a filmmaker over the decades He grew spiritually as well but Year One is a return to the broad, anything-for-a-laugh vulgarity of Animal House and Caddyshack. Only not funny. Really, really not funny.

To aid him in his quest for big, scatological laughs, Ramis hooked up with the hottest name in comedy at the time: Judd Apatow as well as the writing team of Lee Eisenberg and Gene Stupnitsky, a pair of hotshot television writers best known for their work on The Office who also wrote a Ghostbusters III script that, needless to say, has not yet gone into production.

With Year One, Ramis regressed back to the anything-for-a-laugh broadness of Caddyshack. The movie was a throwback in other ways as well. It would make much more sense as a follow-up to Caddyshack released as part of a strange mini-trend in wacky, broad, purposefully hysterical historical comedies like Caveman, History Of The World Part 1 and Wholly Moses.

Yes, they sure don’t make them like Year One anymore. That’s for a very good reason: it’s terrible. Year One’s premise is so threadbare and its script so devoid of wit that not even a brilliant director/co-writer/supporting actor and a preponderance of funny people in front of the camera can manage as much as a few meager chuckles.

Jack Black stars as his stock character, a, rock-and-roll dude named Zed who talks and acts like he’s hitting up a weed dispensary in Burbank even though he lives in what somehow appears to be both prehistoric times and a whole bunch of biblical eras all smashed together. Michael Cera joins Black in fruitless self-caricature as his stock character, in this case a gatherer named Oh. Like pretty much every character Cera plays, he’s a meek, gamine, tremblingly earnest man-child who floats forlornly from one humiliation to another.

In the film’s nadir, Oh spends what feels like a good hour and a half rubbing hot oil all over the mountainous torso of a mincingly effeminate priest played by a career-worst Oliver Platt (who, in keeping with the 1982 vibe, seems to be channeling Dom DeLuise ) in one of many gags rooted in discomfort over homosexuality.

Ramis was a smart man, and a spiritual man, and a political man, so it’s unfortunate that he ended his career with a film that’s sexist and homophobic, but also has the distinction of never being funny. Year One’s plot kicks off with Zed violating his tribe’s most sacred rule and eating from the tree of knowledge. This leads Zed to believe that he has a great destiny, a destiny designed to serve as a connective tissue for a rambling series of encounters.

This leads to Zed and Oh being banished out into the wilderness, where they end up running into a wide variety of kooky characters from the bible played by familiar faces, many from Apatow’s repertory company, like Christopher Mintz-Plasse as Isaac and Paul Rudd as Abel. Like Caddyshack, the film is essentially a collection of sketch-like vignettes with a heavy emphasis on scatology and juvenile hijinks.

There’s nothing wrong with making a movie solely devoted to the feverish, undignified pursuit of laughter. The problem arises when a film exclusively devoted to making people laugh is unable to produce a single chuckle. I was first exposed to Year One before its release, when Ramis came to Chicago, where I was living at the time, and showed a bunch of clips as part of a benefit for a Jewish organization. I remember finding the excerpts funny but I don’t know whether that’s because I was genuinely amused or because Ramis was in the room, and he seemed like such a nice, earnest, sincere, funny and open man who saw Year One as a light, goofy, raunchy comedy, sure, but also one that reflected some of his philosophical and storytelling concerns as well that it would be rude not to laugh.

I was much less impressed when I saw the film in its entirety at the time of its release, and I was even less amused the second time around. Ramis was a craftsman, and a professional, and a man who understood comedy like few others but Year One isn’t just devoid of the maturity and depth of his later work: it’s devoid of the unselfconscious hilarity of his earlier work as well.

Caddyshack thrived on the chemistry of a once-in-a-lifetime cast, particularly the oil and water dynamic of Knight and Dangerfield, but Black and Cera just seem like two generally funny but overwhelmed dudes who were randomly thrown together and, like everyone here, just tried to make the best of a bad situation.

Instead of a return to his Animal House/Caddyshack days of pure, anarchic comedy, Ramis instead regressed with a film that was received less like Caddyshack than Caddyshack 2. Not everything Ramis wrote or directed was a gem: he was often brought in to help save dodgy projects, and almost invariably improved them immeasurably but Year One was a dodgy idea and a dodgy project not even his comic genius could salvage. Ramis was a quintessential comedy fixer, but Year One has problems no one could solve.

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only!

PLUS, for a limited time only, get a FREE copy of The Weird A-Coloring to Al when you buy any other book in the Happy Place store!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!