Cult Auteur Larry Cohen's Directorial Career Began and Ended With Two Very Different Depictions of Black Masculinity in 1971's Bone and the Blaxploitation Team-Up Throwback Original Gangsters

When Larry Cohen died in 2019, he hadn’t directed a feature film in twenty three years, since 1996’s Original Gangstas. But the iconoclastic filmmaker and horror icon was anything but forgotten. He was the subject of 2017’s King Cohen, a well-received documentary on his life and work, a theatrical production based on Cohen’s screenplay for Phone Booth is scheduled to debut in Atlanta in June and b movie aficionados continue to find his work on streaming services like Shudder.

Cohen was unmistakably a product of his times, a hotshot screenwriter turned director with a singular genius for investing funky, commercial genre films with sly satire and unexpected social commentary. Cohen’s riveting 1972 directorial debut Bone, which Cohen also wrote, produced, and filmed partially at his own home explored the anxiety, despair and terror at the heart of American life through one very eventful day in Beverly Hills, California.

Cohen was plugged into the countercultural, revolutionary spirit of the time both in terms of his debut’s audacious, confrontational treatment of race, gender, sex and class but also in the debt Bone owes to the French New Wave, the incendiary style and substance of New Hollywood and a Blaxploitation revolution that alternately exploited, subverted and lampooned stereotypes of African-Americans as hyper-sexual, violent and innately blessed with an effortless cool white America could emulate and imitate but never truly possess.

Cohen’s bold provocation chronicles with unsparing wit and ruthless honesty, what happens when the lives of Bill (Andrew Duggan), an insecure used car mogul famous for his television commercials, and his neurotic wife Bernadette (Joyce Van Patten) collide with that of the title character, a powerfully built black criminal played by Yaphet Kotto when he shows up unexpectedly at their Beverly Hills mansion one day and threatens to sexually assault Bernadette unless her terrified husband returns with five thousand dollars.

Bone doesn’t have to tug very hard for the fabric just barely holding Bill and Bernadette’s lives together to unravel completely, revealing cynical, mercenary calculation and betrayal. In a Ransom of Red Chief turn of events, once Bill gets to the bank to withdraw the money that will save his wife he realizes that he has other, possibly superior options to explore.

Instead of taking out the money, Bill gets a little drunk and briefly falls under the gamine spell of a beautiful young woman played by Jeannie Berlin, who lives in a weird, wild, beautiful world of her own that could not be more removed from the conformity and greed that rule Bill’s staid, moneyed but miserable existence.

Like her mother Elaine May, who used footage from her daughter’s masterful performance in Bone to convince executives to cast her in the role in The Heartbreak Kid that would win her an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress, Berlin is an utter rarity in American film and pop culture as a whole: an absolute original. She’s such an audacious presence that her introduction completely transforms Bone. She’s a Manic Pixie Dream Girl with soul, a damaged, fragile free spirit and professional eccentric whose life consists of one long, weird grift made up of a million little cons.

Berlin’s unnamed character, known only as “The Girl” transforms Bone from a theatrical, intense exploration of racial fear and desire into one of those curious satirical character studies of the late 1960s and 1970s, like Save the Tiger or Joe or I Love You Alice B. Toklas, where a grizzled, middle-aged or older embodiment of white, wealthy male authority takes advantage of the exciting, terrifying sexual freedoms of the day with the help of gorgeous hippie girls who are tantalizingly free and open with their sexuality.

Duggan and Berlin have improbable but intense chemistry. Bill begins the film in a state of depression and free-floating despair, on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The stress of the home invasion pushes him over the edge, sending him free falling into a state of complete psychological disrepair.

Things take an equally unexpected turn back at the mansion, when Bone and Bernadette come to a realization that the roles society has pushed them into, of glowering sexual threat and terrified trophy wife respectively, no longer suit them, if they ever did, and form a new bond rooted in mutual self-interest, hostility towards Bill for going AWOL for selfish reasons, and sexual attraction.

Working with veteran cinematographer George Folsey, the Susan Lucci of film with thirteen Oscar nominations and zero wins, and Folsey’s editor son George Folsey Jr., who would go on to work on projects like The Blues Brothers, Animal House and the “Thriller” video, Cohen created a unique combination of brutal social satire, pitch-black comedy and racially-tinged psychodrama filled with experimental touches, like surrealistic fantasy sequences involving Bill filming ghoulish car commercials full of sex and death and shots of Bill and Bernadette’s son, who they insist is in Vietnam when he’s actually rotting away in prison abroad for smuggling Hash.

Like much of Cohen’s later work, Bone is viscerally exciting pulp that’s overflowing with provocative ideas about race, sex, gender and the seamy underbelly of the American dream. Cohen was holding a magnifying glass up to a society coming apart at the seams and some very different, very damaged people just trying to hold on.

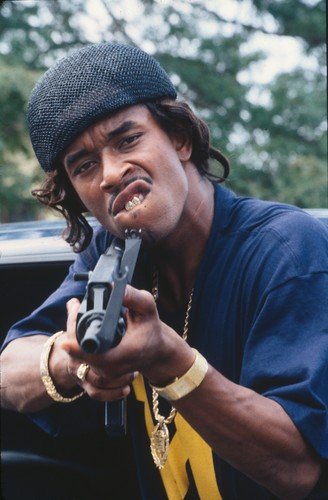

Cohen ended an auspicious if all too brief directorial career by reconnecting with Fred Williamson, the cigar-smoking tough guy star of his second and third directorial efforts, 1972’s Black Caesar and its 1973 sequel Hell Up in Harlem, along with a murderer’s row of blaxploitation legends—Jim Brown, Pam Grier, Richard Roundtree, Ron O’Neal, Paul Winfield—for 1996’s Original Gangstas.

The film’s title is literal as well as symbolic. These icons of unapologetic blackness have all earned the honor of original gangsta through their badassery onscreen and off, on football fields as well as movie sets and theater stages. But Williamson’s John Bookman, Brown’s Jake Trevor, Grier’s Laurie Thompson and Richard Roundtree’s Slick are also all original members of the Rebels, the vicious street gang that brings down the wrath of their elders when they kill hotshot basketball prospect Kenny Thompson (Timothy Lewis) in a drive-by in retribution for one of its members getting hustled by him in a game of one-on one.

When honest shopkeeper Marvin Bookman (Oscar Brown Jr.) nearly gets killed for giving the police the license number of the car that performed the aforementioned drive-by, the small business owner’s hotshot NFL veteran son John (Williamson) returns to his hometown to discover that Gary, Indiana has become a bleak dystopia full of empty buildings and neighborhoods, rampant crime and drug-dealing, murderous gangs like The Rebels, The Diablos and The Rangers.

Jim Brown’s Trevor returns home upon learning of the violent death of a son he never knew but never stopped loving and joins forces with John and Laurie (Grier), the murdered boy’s mother and his own ex-girlfriend, in an attempt to end the Rebels’ reign of violent terror and bring peace and order back to the old hood.

The great Paul Winfield is terrific in the film’s meatiest, most complex and challenging role, playing the ruthlessly pragmatic Reverend Dorsey, an upstanding man of God who is willing to put up with all manner of unGodly behavior for the sake of avoiding further bloodshed and violence. Grier, only a year away from her comeback role in Jackie Brown, brings fierce magnetism and dramatic chops to the role of a street-smart survivor coping with unimaginable personal loss.

Like the character he plays here, Williamson was a star athlete and NFL vet as well as a man born and raised in Gary, Indiana. Williamson was also the film’s producer, which helps explain why he handles much of the film’s hand-to-hand fighting. As with the later, lesser films of Charles Bronson, Original Gangstas’ crowd-pleasing portrayal of men deep into their golden years effortlessly putting down three or four anonymous henchmen young enough to be their son at a time requires suspension of disbelief and no small amount of cognitive dissonance.

Yes, time seems to slow down for John and the movie so that these suspiciously slow and easy to defeat young men can be bested by the improbable one-man wrecking crew that is the movie’s protagonist/producer. Original Gangstas was touted as a movie that reunited the brightest lights of early 1970s black independent film but Williamson is unmistakably the lead the same way The Expendables, which this resembles at times in its star-studded, “Let’s get the band back together” vibe, is famously Sylvester Stallone and THEN everyone else in action movies.

Original Gangstas opens with dry narration explaining how Gary, Indiana devolved from a thriving, Midwestern home of industry and hope (not to mention the singing, dancing, Moonwalking Jackson family) to a grim, seemingly deserted urban hellscape that seems to be on fire much of the time in a way that suggests a Mad Max-style post-apocalyptic waking nightmare more than an unusually troubled American city in the 1990s.

Gary is such a central, tragic character in Original Gangstas, the inner city that we collectively gave up on, a place where dreams die terrible, unmourned deaths, that it seems unfair that the filmmakers felt they had to blow up and burn down seemingly some of the only places in the city that had not already been reduced to rubble by the devastating combined forces of poverty, crime and hopelessness.

Cohen, working from a screenplay by Aubrey K. Rattan, is plugged into the socioeconomic and political factors that lead to the rise of gangs and epidemic levels of crime to the point of being didactic. Original Gangstas, the only feature film Cohen directed that he did not write, is consequently a fascinating, unique combination of blaxploitation throwback (he could not have a better cast for that), nouveau-blaxploitation b-movie and a late in the game version of the “Hood Movie”, socially conscious explorations of life in our inner cities that thrived briefly in the aftermath of Boyz N The Hood’s paradigm-shifting breakout success.

At Williamson’s urging, Original Gangstas was filmed in Gary with a cast that includes any number of real-life gang members who jumped at a chance to work in movies alongside a cast of legends. This helps give the movie a bracing sense of verisimilitude despite its pulpiness and weakness for big speeches and blood-stained melodrama.

Given its roots in blaxploitation, it seems fitting that Original Gangstas shares that alternately loved and hated sub-genre’s virtues and flaws. Original Gangstas is never stronger than when it lets the seductive grooves and passionate lyrics of a soundtrack that alternates between soul music hearkening back to its cast’s golden years and newfangled gangsta rap, carry the movie’s themes and emotions rather than a sometimes clunky script.

In true blaxploitation fashion, Original Gangstas is full of stereotypes of young black men as bloodthirsty criminals and murderers, gratuitous violence and occasionally wooden acting and writing. But it’s also exciting, blessed with charismatic leads with built-in chemistry and explores communities and neighborhoods that the rest of the entertainment world, and society as a whole, would rather pretend do not exist.

Cohen’s career illustrates that you don’t have to choose between being an exploitation filmmaker and a filmmaker of ideas. Cohen’s best movies, like Bone, prove that exploitation movies and genre movies can also be wonderful vehicles to explore subversive and satirical ideas about society and its horrific iniquities.

With Original Gangstas, the old collided with the new. The faces and outsized personalities of a glorious, complicated and contradictory era of black independent film faced off against a new breed of gangsta in a movie that brought together blaxploitation and the hood movie in a combustible but weirdly compelling tribute to a bygone era that continues to cast a long shadow over black film’s present and future.

Cohen once again took material that was commercial and genre-friendly and made something unexpectedly rich and substantive out of it. Cohen ended his feature film directing career prematurely, as he would not die for over twenty years and kept busy as a screenwriter with films like Phone Booth and Cellular, but enjoyably with a movie that Trojan-horsed sober social commentary inside an over-achieving, star-studded b-movie.

Check out my newest literary endeavor, The Joy of Trash: Flaming Garbage Fire Extended Edition at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop and get a free, signed "Weird Al” Yankovic-themed coloring book for free! Just 18.75, shipping and taxes included! Or, for just 25 dollars, you can get a hardcover “Joy of Positivity” edition signed (by Felipe and myself) and numbered (to 100) copy with a hand-written recommendation from me within its pages. It’s truly a one-of-a-kind collectible!

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash from Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Joy-Trash-Nathan-Definitive-Everything/dp/B09NR9NTB4/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr= but why would you want to do that?

Check out my new Substack at https://nathanrabin.substack.com/

And we would love it if you would pledge to the site’s Patreon as well. https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace