It Took Three Decades But 1994's Clifford Is Finally Getting the Acclaim and Respect It Deserves

There is a wonderfully subversive moment late in Clifford’s third act when murdering a child is presented as a choice that is at once understandable, potentially justified, and possibly moral.

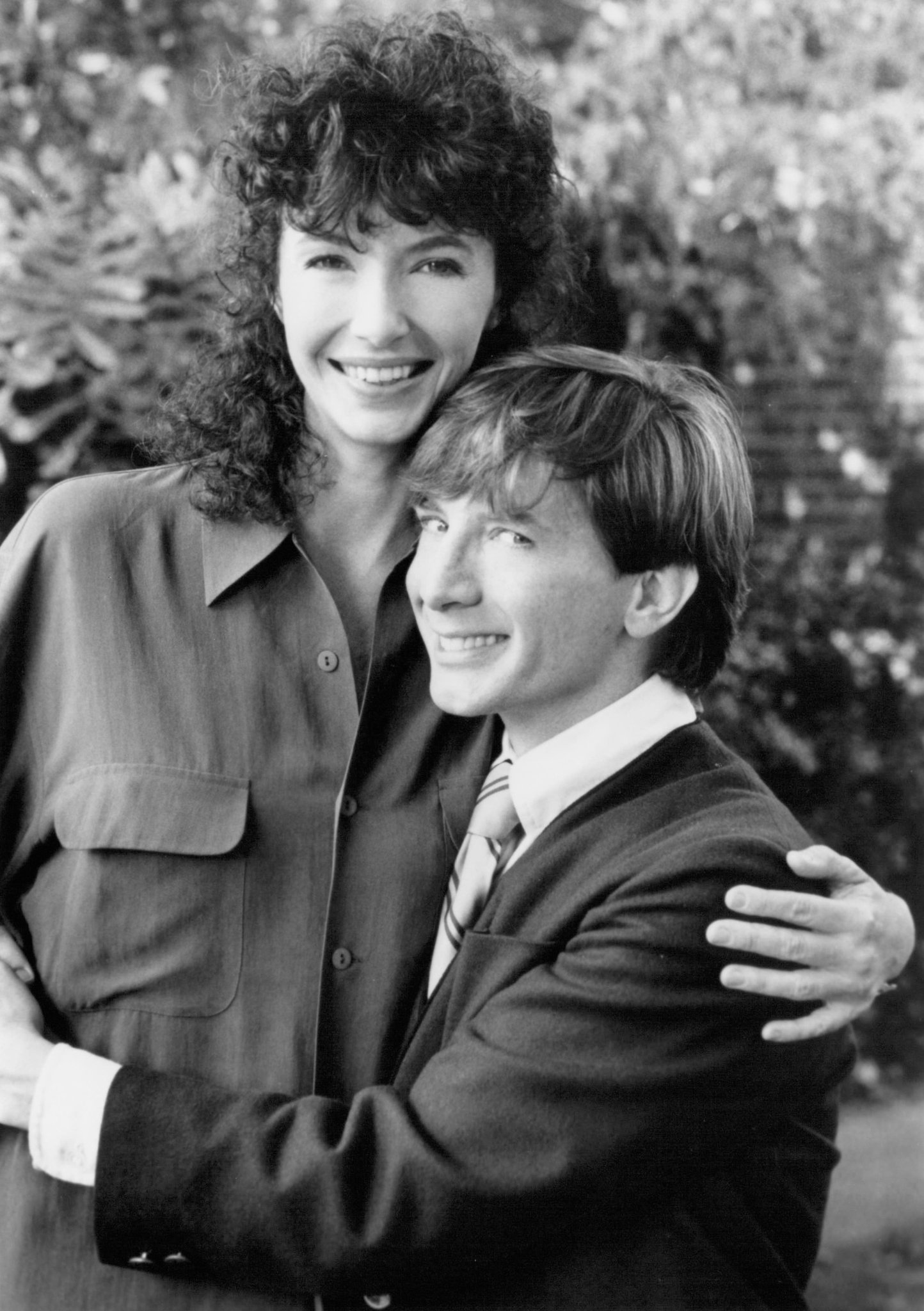

After terrorizing his Uncle Martin (Charles Grodin) in a way that nearly destroys his life, career, and reputation, Martin Short’s iconic title character teeters on the precipice of death as he dangles over a ferocious, enormous animatronic dinosaur.

Martin knows that he should probably keep the ten-year-old in his care from plummeting to a messy, violent death, particularly since they’re family. Yet he is also concerned that he might unleash a great evil upon the world by letting Clifford live and wreak havoc another day.

This is not an unmerited concern. From what we’ve seen, Clifford may go down a very bad road and end up a serial killer, genocidal dictator, cult leader, or Trump supporter.

The film’s answer to “Should this child be murdered?” is seemingly, “Maybe?”

Hell, it doesn’t seem entirely out of the question that, if allowed to live into adulthood, Clifford could cause an apocalyptic event that results in the end of life on earth.

By that point, we know that, surprisingly, Clifford does not end up a mass murderer. That’s because, in a desperate, wholly unsuccessful attempt to make an evisceratingly dark comedy about a ten-year-old boy even a mother would want to murder in his sleep less bleak, a framing device was added after the film was completed in 1990.

Clifford opens with Martin Short in old man make-up and priestly garb in the year 2050. He’s a priest at a school for troubled boys who tells a particularly ill-behaved juvenile delinquent played by Ben Savage a story about his own rebellious youth.

We know from the beginning that Clifford turns out well, assuming that you hold priests in high regard. A happy ending is consequently pre-ordained. The movie is letting us know that Clifford will not die or bring about the end of humanity, even though both seem like definite possibilities.

The studio was understandably terrified that audiences would violently reject a movie in which a little boy is not just unlikable, unsympathetic, and unrelatable but rather a volcanic, seemingly unstoppable force for evil, like Jason Voorhees in short pants.

Casting a thirty-seven-year-old grown-up as a ten-year-old boy is a conceit bold to the point of being avant-garde. It’s also incredibly off-putting. Audiences responded to Clifford’s existence with a befuddled, “What the fuck?” and “Is this some sort of joke?”

Of course, adults play children onstage and on television all the time, particularly in sketch comedy. But it is much rarer for an adult to play a child as the lead character in a feature film.

In Clifford, Short consequently delivers something rare, unique, and wonderful: a performance unlike any in the history of American film.

Short was inspired by The Bad Seed, the timeless camp classic about an evil little girl. This helps explain why Clifford seems less mischievous than psychotic and insane.

Grodin’s Uncle Martin is the perfect comic foil for Clifford. He’s not likable so much as he is less evil than his nephew.

American film and pop culture are cursed with the Cult of Likability. We’re enraptured with the idea that protagonists must be likable and sympathetic, or we won’t be able to identify with them, root for them, or find their struggles compelling.

Individually and collectively, Grodin and Short commit to being deeply unlikable and unsympathetic. It’s goddamn heroic how aggressively non-heroic the characters and performances are.

Grodin plays Uncle Martin as one of his signature weirdly lovable grouches. He’s a misanthropic workaholic who hates children and lives for his work and his child-loving girlfriend, Sarah Davis Daniels (Mary Steenburgen).

Clifford and Martin are like cartoon characters with one goal that they pursue relentlessly. For Martin, it’s getting rid of Clifford without betraying his raging contempt for children to the woman he wants to spend the rest of his life with. For Clifford, it’s going to Dinosaur Land, a prehistoric theme park and a paradise for strange children like Clifford.

Before Clifford can vex and hex his poor relation, he is first the wholly unwanted responsibility of dad Dr. Julian Daniels (Richard Kind) and Theodora (Jennifer Savidge) as they embark on a trip to Hawaii.

Constant exposure to Clifford has clearly taken a toll on these wary souls. They seem understandably beaten down by the trauma. So when Clifford’s parents have an opportunity to pawn him off on the dad’s brother, they leap at the chance.

Uncle Martin has an agenda of his own. He wants to prove to his understanably skeptical partner that he’s not the W.C. Fields-like curmudgeon she thinks he is but rather someone eager to embark on the great and terrible adventure of parenthood.

In a line that has been lionized on The Best Show, the universal epicenter of Clifford super-fandom, when Martin is asked the name of the nephew he professes to adore he guesses, with just the right note of obliviousness, “I want to say Mason.”

Other Clifford superfans include Nicolas Cage (who loved the film so much that he apparently accosted Short in public to gush about his favorite scenes), Harold Ramis, Elizabeth Taylor and Steven Spielberg.

Sarah’s suspicions involving Martin’s readiness for fatherhood are not assuaged by him showing her his dream home, a hideous black box in front of a cliff.

Clifford has two primary modes. When he wants something he’s a sticky sweet sycophant oozing fake praise and positivity along with veiled and not so veiled insults.

When Clifford is being his true, evil self he gets a crazed gleam in his eyes that betrays that something very bad is about to happen imminently.

Clifford has Uncle Martin try to not let his nephew destroy his life, career, relationship and reputation while preparing for an all-important work event where he will unveil his vision for Los Angeles’ public transit system.

Martin is being sabotaged by scheming boss Gerald Ellis (Dabney Coleman), who wants his employee out of the way so that he can put the moves on his girlfriend. There’s not much more to the character than a toupee so glaringly obvious that it makes Grodin’s seem less conspicuous by comparison.

Grodin was one of our great comic character actors. But he was an even better reactor. In Clifford Grodin and Short achieved an ideal of collaboration and improvisation where two beautiful comic minds and bodies are working in perfect harmony.

Clifford is a gorgeous vehicle for the sputtering, barely repressed rage that Grodin did better than just about anyone. He is perpetually apoplectic, forever overcome with rage toward a demon in the form of a child who has hit his life with the destructive force of a biblical plague.

Short, meanwhile, delights in playing the most obnoxious brat in the history of the universe.

Clifford is an outsized live action cartoon with Clifford as Bugs Bunny and Martin as a forever foiled Yosemite Sam figure. Yet it’s also strangely relatable. I have an exceedingly smart, strange, intense and mischievous nine year old who has more than a little Clifford in him.

On more than one occasion I’ve say opposite him after and thought, “Look at me like a real human boy!”

It doesn’t matter that everything around Grodin and Short’s performances are sloppy and arbitrary.

Clifford IS Charles Grodin and Martin Short. It is consequently both hilarious and utterly unique, a rare and remarkable combination.

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here

AND you can buy my books, signed, from me, at the site’s shop here