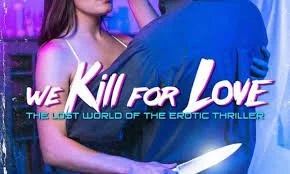

My Shudder Pick of the Month is We Kill for Love, a Nearly Three Hour Long Deep Dive Into the Lost World of Direct-to-Video Erotic Thrillers

When it comes to prospective entries in The Fractured Mirror, my epic upcoming tome about American movies about filmmaking, I ask myself four questions. First, I ask if the movie fits the criteria for the book, which I will concede can be a little fuzzy. Many of the movies in my book are very overtly about the film industry. With some movies chronicled, however, movie-making figures less prominently.

If I determine that a movie fits the criteria, I then ask, “Does this movie NEED to be in the book?”, “Will anybody notice or mind if it’s not in the book?”, and finally, “Will the book be even a tiny bit better by its inclusion?”

There are exceptions, like Crimes and Misdemeanors, but movies added very late in the process don’t NEED to be in the book. Furthermore, it’s unlikely that anyone would notice, let alone become enraged, by the absence of something like 1957’s The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown.

The Jane Russell vehicle is obscure, but I cover movies that are far less well-known in the book because I write about everything.

I’ve added dozens of movies after ostensibly finishing ages ago because they make the book better, more complete, and more exhaustive. They also make it longer, which helps explain why the current, nearly finished draft is 528 pages.

When I visited Shudder for a movie to write about this month, I was irrevocably drawn to We Kill For Love, a two-hour and forty-three-minute-long documentary about direct-to-video erotic thrillers of the 1990s.

Does We Kill for Love need to be in the book? No, it does not. Would anyone notice if it wasn’t in the book? Probably not, although my audience, god bless them, is precisely the demographic that would be intrigued and excited rather than horrified by the existence of a nearly three-hour-long tribute to the movies I used as masturbatory fodder throughout my teen years.

To answer the final, most important question, will The Fractured Mirror be a better book if it includes We Kill For Love?’ The answer is yes. That’s all I needed to devote 163 minutes to a surprisingly cerebral exploration of the kind of shit that played on Cinemax late at night, and earned it the affectionate nickname Skinemax.

Fatal Attraction may have influenced some direct-to-video erotic thrillers.

When I was a kid, my special interest was scouring video store shelves to see which movies had naked boobs in them. My teenage years occurred during the heyday of the direct-to-video erotic thriller. I was a video store clerk throughout my later teen years, so I rented out these erotic outings as well. Seeing trade ads for Shannon Tweed vehicles brought me back to my high school years, when I worked as a Customer Service Representative at Blockbuster Video.

As an adult, my special interest is movies about movies. So it was perhaps inevitable that I’d end up watching and writing about a film that feels like it was made for me.

With 2023’s We Kill for Love, Clinton-era fuck-films that skipped the multiplex en route to Mom and Pop video stores, Cinemax, and The Playboy Channel get their own Los Angeles Plays Itself.

Like Thom Anderson and his iconic film essay, We Kill For Love writer-director Anthony Penta has thought long and hard about something most people don’t think about at all.

For Anderson, that object of obsession is the oft-overlooked role Los Angeles plays in movies filmed there. For Penta, it’s exploring the origins and surprisingly complicated and nuanced gender and class issues at play in a subgenre the public thinks about solely in terms of sex and sensationalism when they think about it at all.

We Kill For Love opens by treating its seedy subject matter with a seriousness that borders on self-parody. Michael Reed plays an enigmatic figure known as “The Archivist.”

The Archivist is a stand-in for a writer-director intent on exploring this half-forgotten yet fondly remembered world with insatiable curiosity, unmistakable fondness, and surprising academic rigor.

We begin by examining the relatively highbrow inspirations behind low-budget video store fare, which is designed to satisfy the quick and dirty needs of onanists, rather than comment meaningfully on society.

The direct-to-video erotic thriller has its roots in film noir, most notably Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity. Film noir, in turn, grew out of hardboiled pulp magazines and lurid pulp paperbacks from Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain.

Direct-to-video erotic thrillers are the disreputable bastard child of film noir and hard-boiled fiction.

Film noir led irrevocably to neo-noir. Body Heat was the Big Bang for neo-noir. Lawrence Kasdan’s directorial debut offered a newfangled look at what We Kill For Love argues is the core message of erotic thrillers: sex is dangerous.

Body Heat has the look and feel, as well as the scorching sexuality, of classic film noirs, but it also has substance. The same could not be said of many of its imitators, which kept the steamy stylization but ditched the artistry and craft.

As a child of the 1980s, I was taught that sex was dangerous. We all were. From the time I was a small child, sex was irrevocably associated in the public mind with death.

It was drilled into us, individually and as a generation, that if you had sex, you’d get AIDS, then you’d get the girl pregnant, then the baby would have AIDS. It’d be a whole thing.

Direct-to-video erotic thrillers applied the free-floating cultural anxiety about STDs to secret heterosexual unions that invariably blow up in a dangerous and destructive way.

We Kill For Love is obsessed with the complicated gender politics of a subgenre that’s sexist, exploitative, and objectifying on the surface but more complicated and ambivalent underneath.

In that respect, it followed in the path of its more respectable father, film noir. Femme fatales are destructive, scheming divas who lie and cheat and toy with the hearts and minds of gullible, horny men like cats playing with a terrified mouse.

But femme fatales, both old school and Cinemax-ready, were also strong, confident, sexy, and sexually assertive in a way that makes men and society uncomfortable as well as horny.

We Kill For Love posits that one of the overlooked strengths of the direct-to-video erotic thriller lies in its subversive embrace and exploration of female sexual desire.

The late Zalman King figures prominently here not as a sleaze merchant or softcore titan but rather as an artist. We Kill For Love sees him as a visionary with an intense interest in beauty and female sexual desire.

We Kill For Love goes a little overboard in its deification of King, but he’s the closest the disreputable subgenre came to an auteur whose work defines it.

The direct-to-video erotic thriller generated its own set of superstars, chief among them Shannon Tweed and, to a lesser extent, her sister Tracy. If King was, well, the King of stuff that would pop up on Cinemax after the kiddies have gone to bed, then Tweed was the queen.

I was disappointed that Tweed is not among the luminaries interviewed. I blame Gene Simmons. Shannon Whirry is also absent, but they have secured the participation of Andrew Stevens, a Nepo Baby and giant in the field, as both an actor and a filmmaker.

Famous faces and familiar names, such as Drew Barrymore, Alyssa Milano, and Molly Ringwald, dabbled in image-altering erotic thrillers but had the luxury of returning to more straightlaced fare. They were tourists in this world where various sexpots interviewed here were permanent residents.

We Kill For Love does not delineate between low-budget erotic opuses created by cynical specialists for the home market and movies by auteurs like Wayne Wang, Atom Egoyan, and Paul Verhoeven who make movies with sex.

This deep dive into the steamy fare that dominated small video stores in the 1990s opens in an unexpectedly yet refreshingly cerebral fashion. It gets less high-minded as it progresses and grows more personal.

The film may take erotic thrillers seriously, but the filmmakers, actors, and actresses interviewed do not. They’re happy to discuss the absurdity of their work and its endlessly exhausted cliches, like the ubiquitous overhead fan and sexy red sports car of doom.

Just as Crystal Lake Memories, the nearly seven hour documentary about Friday the 13th that I also cover in The Fractured Mirror, made me want to binge-watch the franchise despite having no real love for it, We Kill For Love made me nostalgic for movies that are, objectively, quite poor, but served as essential function in giving onanists like the teenage me something to watch while masturbating furiously.

The death of mom and pop video stores, the rise of streaming, and the availability of hardcore free porn spelled doom for erotic thrillers. Why settle for airbrushed simulated sex when the real thing was available to anyone with a laptop and internet?

In We Kill For Love, the heyday of the erotic thriller gave audiences a rare and welcome look into the aggressive female libido. So it makes sense that the genre’s horny spirit lives on in Lifetime TV movies.

We Kill For Love feels much shorter than its 163-minute runtime. I’m glad I chose to watch it because I thoroughly enjoyed it, and its inclusion in The Fractured Mirror is guaranteed to make it at least 0.0000000001 percent better.

That’s enough for me!

You can pre-order The Fractured Mirror here: https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

Nathan needed expensive, life-saving dental implants, and his dental plan didn’t cover them, so he started a GoFundMe at https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-nathans-journey-to-dental-implants. Give if you can!

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here.