Burt Reynolds' Directorial Career Got Off to a Roaring Start with 1976's Kick-ass Gator and Ended with the Aggressively Undistinguished The Last Producer

By the time Burt Reynolds made the leap from leading man to director with 1976’s Gator, the sequel to 1973’s White Lightning, he had mastered the tricky, misunderstood art of being yourself onscreen. As single dad, bootlegger, ex-convict and all-around contemporary swamp legend “Gator” McKlusky, Reynolds oozes pure charm. Mustachioed and understatedly virile, Reynolds knew damn well that he didn’t have to do anything more than smile that infectious smile and laugh that irresistible laugh and we were putty in his hands.

Reynolds was at the peak of his beauty and charisma when he made Gator. Reynolds was so appealing and good-looking in the mid-1970s that he could play a hobo competing for the title of World’s Smelliest Bum and he’d still convincingly get the girl and inspire envy and hero worship from awestruck audiences. Reynolds possessed that kind of swagger. He was the purest of movie stars and the utterly delightful, if decidedly over-long Gator is a wonderful vehicle for Reynolds’ manly charms.

It’s too late to see Gator the way it was meant to be seen, at a drive-in in the Deep South with a joint in one hand and a cheap jug of moonshine in the other, a disreputable romantic companion by your side. But Gator is so wonderfully sordid that it brings a pungent retro drive-in vibe to even the sterile world of online streaming and DVD.

At its best, Gator is wonderfully sleazy, a southern-fried exercise in badassery from one of the masters of the form. Gator peaks early with Jerry Reeds’s wonderful theme song, which was shamefully ignored by the Academy Awards despite the beautiful job it does establishing a tone of dirty greasy southern swamp funk.

If the Okefenokee Swamp, where Gator lives and works, had a sound it would be Reed’s transcendent hillbilly anthem about a man who was “raised in a swamp in back of a slough/He grew up eating rattlesnake meat drinking homemade brew/Now folks call him Gator and everybody knows him well/Meanest man ever to hit the swamps folks swear he come straight out of hell.”

Reed’s song is a bang-up exercise in hillbilly mythologizing but the lyrics about coming straight out of hell apply more directly to Bama McCall, the fascinatingly psychotic villain Reed himself plays here. Bama is less an unusually vicious and depraved criminal than a one-man crime wave. Bama is as long, lean and deadly as a rattlesnake, with the personality to boot. Reed is such a volcanic force, at once wildly charismatic and singularly loathsome, that he threatens to steal the film from Reynolds at his radiant best. Gator may be a bad boy of the swamp but Bama is downright Satanic.

Bama is such a menace that the governor of the state Bama calls home resorts to desperate measures to bring him down. The wonderful Jack Weston brings his neurotic big city Jewish intensity to the role of Irving Greenfield, an exceedingly sweaty Yankee lawman tasked with bringing Bama to justice with the help of Gator, an old friend of Bama’s who knows the inside of prison all too well. Gator sums up the culture at play in Irving Greenfield going deep undercover in the deep South town of Dunston when he tells him, not inaccurately, “You gonna stick out in Dunston like a bagel in a bucket of grits.”

Reynolds and Weston have a winning yin and yang dynamic as mismatched law enforcement buddies; it’s too bad Weston’s gefilte fish out of water does not entirely survive the proceedings or they would be perfect for a buddy comedy spin-off called Bagel and Grits.

Gator goes undercover as Bama’s right hand man but discovers that he cannot work for the man in any capacity after Bama invites him to get his rocks off with a member of his harem of drug-addicted underage child prostitutes.

Reed dominates the film’s first act with his malevolent magnetism. But once Gator, Irving Feldman and sexy, glamorous reporter Aggie Maybank (Lauren Hutton, who would go on to be the leading lady in two subsequent Reynolds vehicles: Paternity and Malone) and eccentric, cat-loving numbers cruncher Emmeline Cavanaugh (Alice Ghostley) decide to go the Elliott Ness route and bring down Bama for financial malfeasance Reed begins to disappear for distressingly long periods of time. The film suffers for his absence.

Reynolds and Hutton have explosive sexual chemistry. They make for preposterously beautiful lovers but the romance here adds greatly to the wildly bloated 116 minute runtime without adding anything essential. This is far too proudly neanderthal a redneck swamp romp to have much use for the civilizing touch of a beautiful woman.

There’s no reason a movie like Gator has to be longer than 85 minutes. Cut a half hour from Gator and you have a cult classic on par with Reynolds’ best work from this period but even with sometimes slack pacing, excessive length and a romance asking politely for the cutting room floor to make more room for awesome stunts Gator is nevertheless a wildly entertaining sleeper that got Reynolds’ career as a director off to a deceptively strong start.

Before he graduated to blockbuster director with the following year’s Smokey and The Bandit, Hal Needham served as both Reynolds’ body double and the film’s second-unit director. Needham, who would go on to win an honorary Academy Award, developed a reputation as a peerless giant of the stunt world. An early set-piece involving government helicopters descending into the bayou to chase Gator’s speedboat through the swamp is a pulse-pounding example of the kind of manly, sweaty stunt magic former stunt man Reynolds and frequent collaborator Needham were capable of at their best.

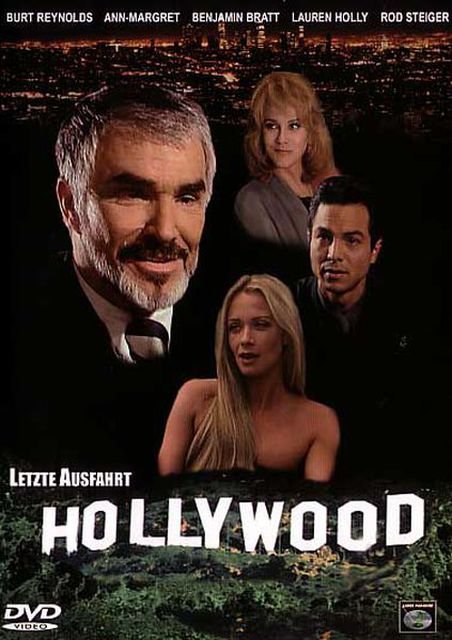

Around a quarter of a century later, Reynolds ended his career as a periodic director of films, TV movies and television shows on a down note with 2000’s The Last Producer, known alternately as The Last Hit. It’s a kitchen sink movie-world comedy melodrama that plot-wise and thematically favorably recall Reynolds’ triumphant, career-best turn as a pornographer with heart in 1997’s Boogie Nights and the hit 1995 Elmore Leonard movie world crime comedy Get Shorty.

The Last Producer at least gives its director and star a juicy role in Sonny Wexler, a 70 year old half-Jewish, half-Native American producer who used to work with the giants of American film back in the good old days but whose fading career is now running on fumes. Sonny’s friends and colleagues have an unfortunate knack for being retired or dead, and consequently unable to help him professionally while the younger generations in the corridors of power view desperate self-promoters like Sonny as irrelevant dinosaurs too deluded to realize their careers are over.

Sonny is just barely hanging on when he gets his hand on a screenplay from unlikely wunderkind Bo Pomerantz (Sean Astin) that is so brilliant and so undeniable that Sonny is certain that he’ll make a fortune off of it if he’s able to raise fifty-thousand dollars in five days in order to retain control of the magical script.

Sonny’s elevator pitch for the screenplay certain to make a fortune for anyone connected to it is an updated version of Clifford Odets’ 1937 melodrama The Golden Boy. Odets was of course perhaps our leading Socialist propagandist, an unapologetic ideologue whose relentlessly political, didactic message plays are unmistakably the product of a time when the dreamers and idealists of the American left romanticized and idealized Communism and Socialism, and political theater was all about uplifting the spirit of the noble working man. Not exactly Neil Simon in terms of broad, mainstream appeal.

It would be difficult to imagine a contemporary pitch less likely to guarantee boffo box-office and a huge payday for everyone involved than “modern-day Clifford Odets” with the possible exception of “Bertolt Brecht, but CGI and for children” but that’s The Last Hit’s idea of a sure-fire commercial conceit all the same. Bo’s screenplay, which sounds terrible but also incredibly non-commercial, promises to change everything but Sonny runs up against fierce opposition in the form of malevolent studio executive Damon Black, whom Benjamin Bratt plays poorly and hammily as the blow-dried, Italian suit-clad embodiment of slick Hollywood corruption.

Can the old-timer out-maneuver the corporate shark? The appropriately named, black-hearted studio executive certainly can’t match our scruffy protagonist when it comes to dropping big names in both a calculating, self-aggrandizing fashion, and to let us know that he and the movie remember and revere a long-ago era when a man like John Huston (who is name-checked repeatedly) strode confidently across studio lots like a modern-day Colossus.

As part of his old-school charm/spiel, Sonny drops the names of classic American studio filmmakers and French giants at a volume that would embarrass Peter Bogdanovich. Like much else in Clyde Hayes’ overstuffed, under-baked screenplay, this rings annoyingly false.

Burt Reynolds was many things in his remarkable lifetime. He was a jock. He was a sex symbol. He was one of the biggest box office attractions of his day. He was an underrated, classically trained actor. He was a populist, popular entertainer. He was the man and the mind behind both The Burt Reynolds Dinner Theater and The Burt Reynolds Institute, where luminaries such as Charles Nelson Reilly and Reynolds himself taught, but he never came off as a snob. That’s one of the reasons the masses related to him on such a deep emotional level: they could tell themselves that he was one of them, a hamburger and beer guy who just happened to be one of the biggest movie stars of the 1970s and 1980s.

So it feels a little jarring and off to see the blue-collar icon wax pretentious about the glorious history of American and international film. It also doesn’t help that The Last Producer doesn’t do anything to invoke Hollywood’s gloried past beyond name-drop famous directors with minimal context.

Reynolds really worked his Rolodex for the film’s ridiculously over-qualified cast, which includes such luminaries as Ann-Margret as Sonny’s pill-addicted, mentally ill glamour girl wife, Charles Durning as Sonny’s hangdog business partner, Robert Goulet and Rod Steiger, who actually starred in a Clifford Odets adaptation in 1955’s The Big Knife, and a badly miscast Lauren Holly as a flirtatious, bored sexpot attracted to our hero’s silver-fox charms.

For a blink-and-you-miss-it poker sequence, Reynolds got Shelly Berman, Shecky Green, Angie Dickinson and Alex Rocco. Reynolds attracted a lot of talent to what is clearly a low-budget movie further hindered by a cloying, distracting smooth jazz score that smothers everything in moody saxophone. But the clunky, over-written, tonally inconsistent screenplay gives its only decent role to its director, whose work here, while solid, can’t compare to similar turns in Boogie Nights and recent Fractured Mirror entry The Last Movie Star, which also drew extensively on their star’s real-life career and persona but gave him a role worthy of his talent and his legacy.

The Last Producer is about a script so improbably brilliant, undeniable and commercial that anyone lucky enough to be able to able to produce it is promised incredible success in an industry where nothing is certain that is creatively knee-capped by a screenplay so dire that not even this all-star roster of seasoned professionals, including the legend in both the lead role and the director’s chair, can make a success.

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out and it is magnificent!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.