Sidney Lumet's Extraordinary Career Began Big with 12 Angry Men and Ended Strongly With the Terrific Neo-Noir Before the Devil Knows You're Dead

By the time Sidney Lumet made his feature-film directorial debut with 1957’s 12 Angry Men he’d already developed a reputation as a master of live television. Lumet learned his craft in the high-pressure, unrelenting world of early television, where a single mistake could spell disaster. Later, Lumet would draw upon those experiences directing Network, the definitive television satire.

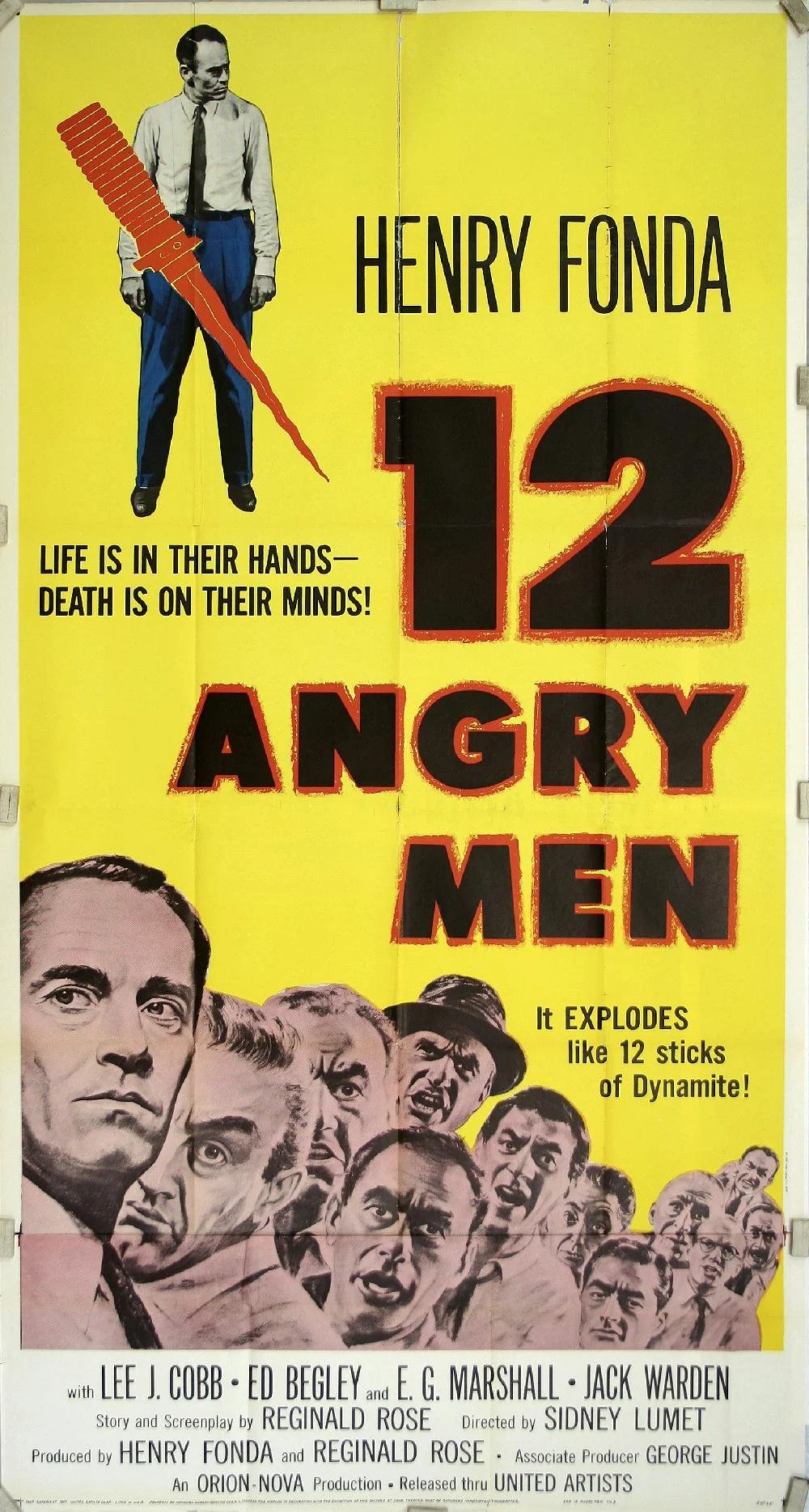

The film that Lumet debuted with began as a 1954 live drama written by Reginald Rose (who would pick up an Emmy for his teleplay, and later be nominated for his screenplay for the film version) and directed by Franklin Schaffner, who would go on to direct the zeitgeist-capturing smashes Planet Of The Apes and Patton. The next year 12 Angry Men made the big leap to the stage, Emmys in tow, before making an even bigger leap to the big screen two years later.

The 1957 film version of 12 Angry Men was consequently the perfect vessel for Lumet’s transformation into a filmmaker. Like its director, it had a solid background in live television and the stage and played to the up and coming filmmaker’s gift for atmosphere and characterization, masterful acting and stormy emotional intensity.

Lumet’s debut was similarly defined by its social consciousness. Even at the embryonic beginning of what would become an epic half-century long film career, Lumet was already flaunting his fierce Liberal convictions. Lumet was a New York tough guy with a big, bleeding heart who devoted his life and career to making movies about things that mattered: nuclear war, political corruption, intolerance, crime, race, media sensationalism and genocide.

In 12 Angry Men Lumet and his peerless collaborators use the deliberations of one jury tasked with determining the guilt or innocence of an eighteen year old hispanic kid accused of murdering his father as a microcosm for American society at a fraught and uncertain time.

The judge who gives the jury their instructions impresses upon them the seriousness of their task and the stakes at play. But if his words are dramatic and intense, his delivery is perfunctory and bored. Even when informing the jury that a man’s life is at stake, the judge can’t bring himself to pretend that this is anything other than just another day at work for him. He’ll get paid no matter the verdict. It’s the jurists who are only passing through.

#Squadgoals

The jury seems equally intent on going through the motions on what initially appears to be an open-and-shut case until a juror played by Henry Fonda, that steely exemplar of all-American dignity, does something deeply decent and unexpected: he dissents. He asks his colleagues to consider the stakes at play and not send a boy to die without giving his case, and by extension his life, serious thought, and serious consideration.

Fonda’s juror raises his voice to say that maybe the official version isn’t correct, and that an 18 year old kid deserves a fair shake even if the prosecutor seems as ready as everyone else to send the kid to his grave. The next 90 minutes or so follow Fonda as he makes the smart, impassioned and convincing case for the defendant’s innocence the boy’s own lawyer never did.

It’d be hard to imagine a more stagey conceit than 96 minutes in a jury room as twelve men argue an 18-year-old boy’s guilt or innocence. To his credit, Lumet doesn’t try to hide or mask the material’s stage origins. He doesn’t try to “open up” the proceedings with flashbacks. Instead, he leans into sweaty claustrophobia of a dozen representation of American masculinity as their moral certainty is attacked with a powerful one-two punch of logic and human decency.

In this context, “claustrophobic” become positive rather than pejorative. Boris Kaufmann’s haunting black and white cinematography hones in on these desperate men as they wilt under the oppressive heat of what we are told is the hottest day of the year. The film stock itself seems to sweat under the heat, both literal and symbolic.

Lumet’s brilliance as an actor’s director is in full display here. Fonda’s towering presence, at once as big and looming as an oak tree yet strangely fragile, anchors the film. Fonda has an antagonist worthy of him in the character played by Lee J. Cobb. Over the course of the film, the convictions of the ten other men begin to change as one after another is swayed by the logic of Fonda’s underdog hero.

The film was produced by Henry Fonda and Reginald Rose, its star and screenwriter, respectively, so it’s not surprising that their primary goal seems to be honoring the writing and the acting. Lumet understood intuitively that the proceedings are dramatic and compelling enough on their own. Lumet trusts the actors, writing and the audience’s intelligence enough to know that his job as a director is largely to get the hell out of the way.

12 Angry Men is about the legal system but on a broader level, it is about society. The jurors of 12 Angry Men represent a broad cross-section of American masculinity, from a slick ad man to an old man seemingly excited just to have people to talk to. When they talk about the case and the defendant’s innocence or guilt they can’t help but also talk about everything related to it. They can’t help but talk about money and class and race and politics and the impossible gulf between what are known as “the kids” and a grown-up world that worships and condemns youth while only intermittently attempting to understand them.

12 Angry Men is a deeply idealistic defense of not just the American justice system but the American way of life. Its belief in the fundamental goodness of the American character is both poignant and a little heartbreaking. The film argues, with the same passionate conviction its protagonist brings to his initially lonely, but ultimately successful crusade, that our institutions only work if we do our part, if we take citizenship seriously, as something sacred and central to who we are and what we believe in, not some hassle you have to power through in order to get home in time for dinner or a ballgame.

It a serious thing to be given the power of life and death. That is a power wielded by God and it is a measure of the extraordinary faith the American legal system places in the American people that it is also a power offered to everyday Americans. 12 Angry Men argues that we’re worthy of that power, but only if we are our best selves, and approach the task with an appropriate sense of its seriousness. It’s patriotic in a tough, two-fisted, deeply honorable way, a film that embodies who we are at our best.

Lumet finished his 50 year career with a brooding, gritty melodrama about another entity with the power to determine who lives and who dies. Only this time he’s not dealing with God, or the American legal system but rather with criminals who give themselves power over life and death, and end up paying a terrible price for their arrogance.

Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead was a tough film to watch by design. It directs its unblinking gaze at people in the midst of a profound moral and emotional breakdown, people who are desperate, people who are in trouble, people who may very well be beyond redemption. It’s a final film as obsessed with death, and saturated with death, as Robert Altman’s Prairie Home Companion, which attacked the subject of death from a much more whimsical angle.

Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s death from a heroin overdose while in the prime of his career and at the height of its powers casts a long, film noir shadow over the proceedings. It’s damn near impossible to watch Hoffman’s character, Andy Hanson, stumble around in a heroin, cocaine and pot haze, chasing the death and darkness that will inevitably consume him, without thinking of the actor’s own lonely death of a heroin overdose just a few years later.

Like some of Lumet’s best work, Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead is punishingly, almost unbearably intense. It’s a sordid wallow through the ugliest aspects of humanity whose philosophy can be succinctly summed up in the aphorism of an ancient old jewelry fencer Andy Hanson works with, and is in turn betrayed by: “The world is an evil place.”

If the world is an evil place, Hoffman’s darkly charismatic anti-hero is its preeminent demon. He’s the devil on the shoulder of his his weak younger brother Hank (Ethan Hawke, at his sad-eyed, overwhelmed best), encouraging him to be his partner on a plan to rip off their parent’s small-time jewelry shop.

It’s supposed to be a victimless crime costing only his parent’s insurance company but in the grand tradition of crime melodramas, things go terribly awry almost from the start. An ostensibly victimless crime begins to wrack up an awful lot in collateral damage even before the corpses begin to really pile up.

Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead is lurid pulp executed with incongruous high-mindedness. It’s an arthouse noir that finds tragedy and pitch-black dark comedy in a strip mall heist gone bad. It is a terrible thing for a person to lose their life unnecessarily, but it’s even sadder when it happens between a Claire’s Accessory and Foot Locker.

Where 12 Angry Men’s structure is one of elegant simplicity, Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead fractures its timeline and is continually skipping forward and back in time. These shifts in chronology are introduced via smash cuts executed with the pummeling, percussive force of a punch in the face.

Thanks to the film’s time-hopping structure, we know early on that the brother’s scheme will fail, and that all of their furious machinations will amount to nothing but ugliness. This lends the film an overwhelming sense of fatalism. The film’s characters are all profoundly doomed, and on some level, they know it.

Andy Hanson is the catalyst for all of the ugliness and violence in Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead and Hoffman delivers a big, theatrical performance as sort of a dour, bean-counting Falstaff, a man of outsized appetites who fancies himself a mastermind but is fatally incapable of dealing with the chaos and darkness his untamed id has unleashed. He’s monstrous but relatable, a brilliant villain in a movie without any real heroes, just people whose goodness is probably just weakness coupled with an absence of real evil.

The film represented a self-conscious throwback to the New Hollywood of the 1970s, when the studio system was unusually attuned to the lives and angst of small-time hustlers scrambling to eke out an existence and find meaning on the fringes of American society. In that respect, it marked a return to form for Lumet after a rocky 90s and undistinguished aughts. Lumet ended his film career the way he began it, telling a story that appears modest in scope yet is secretly ambitious, a movie about people that’s tough and smart but also empathetic and human. The world of Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead may be evil, but like so many of Lumet’s movies, it’s also endlessly compelling.

Send me to prison where I belong! I just launched a GoFundMe for the first ever Blues Brothers Convention at Joliet Prison, which you can be a part of by donating over at https://www.gofundme.com/f/send-nathan-to-the-blues-brothers-convention

Did you miss the Kickstarter campaign for The Fractured Mirror, the Happy Place’s 600 page opus about EVERY American movie ever made about the film industry? Then you’re in luck! You can still make the magic happen over at Make it happen over at https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 16.50, shipping, handling and taxes included, 30 bucks for two books, domestic only!

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!