Singing in the Rain's Enduring Greatness Lies in its Proud Vulgarity

When Stanley Donen passed away at the ripe old age of 94 his legacy was staggering, his body of work incredible. The legendary choreographer and filmmaker’s achievements include co-directing a motion picture that is perpetually in the mix when the subject is the best movie of all time, as well as the best comedy of all time, the best musical of all time and the best movie about movies of all time.

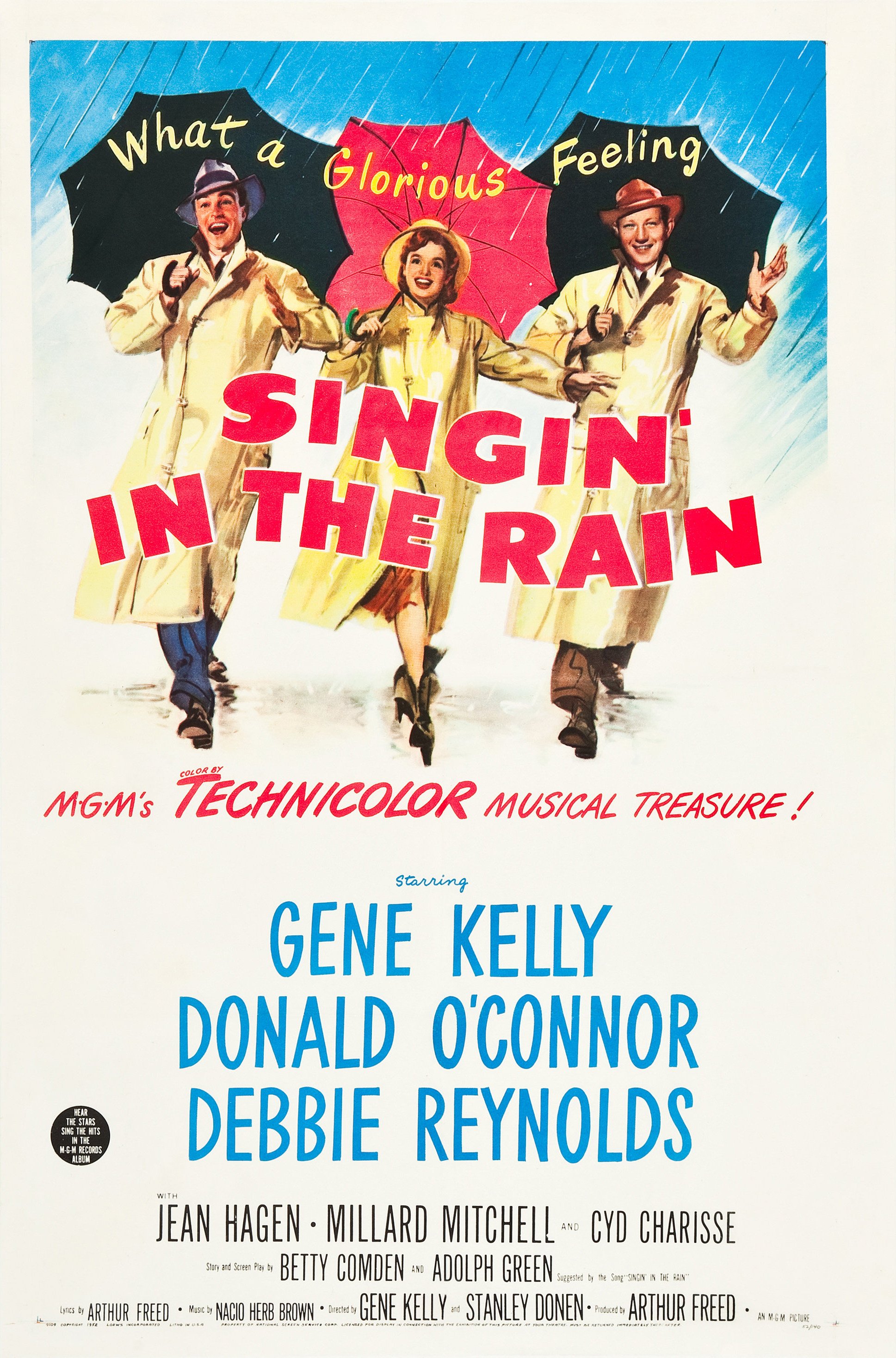

I’m talking of course about Donen and co-director Gene Kelly’s timeless masterpiece 1952’s Singing in the Rain. When movies take up a permanent place of pride in the pantheon of Great Films it is frequently because they’re about Important Subjects, adapt Important Books, tackle Great Lives or single-handedly propel the technological craft as well as art of film forward by leaps and bounds, like Citizen Kane.

Films heralded as the best of all time frequently broadcast their ambition, significance and importance from the mountaintops. These are Serious Films like Citizen Kane or Gone With the Wind or Lawrence of Arabia about serious subjects with serious budgets. These movies are bandied about as all-time greats in no small part because they nakedly aspire to greatness.

Sining in the Rain, in sharp, delightful contrast, has earned a permanent place high atop the pantheon of all-time Greats not by being overly Serious (perish the thought) or addressing Important Subjects or Documenting Important Lives but rather by virtue of being an obscene amount of fun.

Where its contenders for the crown of best film are clearly the products of Artists who take themselves and their art very seriously, Singing in the Rain is unabashedly the brainchild of entertainers, for whom putting on a damn good show trumps all.

Singing in the Rain isn’t just an anomaly in the pantheon of Great American films in its lack of dour solemnity and gravitas. No, Singing in the Rain is spectacularly, purposefully, transcendently silly, a gloriously vulgar romp full of clamorous ditties that aren’t catchy so much as they are annoyingly infectious, the kind of ear worm you can’t get out of your head no matter how hard you try.

The wonderfully inane songs that give Singing in the Rain so much of its manic energy and pep were largely co-written by Nacio Herb Brown and lyricist Arthur Freed, who did double duty as the head of MGM’s legendary Freed Unit, although screenwriters Adolf Green and Betty Comden, talented songwriters in their own right, wrote “Moses Supposes.”

It almost doesn’t seem fair that one man could be gifted enough to produce many of the greatest musicals of all time and write any number of distressingly infectious pop songs but like many of the people associated with Singing in the Rain, Freed was preposterously talented and accomplished in more than one field.

Singing in the Rain was conceived partially as a clearinghouse for Freed-Brown ditties from throughout the decades, many of which had already been used prominently in other musicals. Part of what makes Singing in the Rain so delightfully subversive and anarchic is that the screenwriting team of Comden-Green and the directing team of Kelly-Donen are making fun of their boss as much as they’re celebrating him. .

These wisenheimers aren’t presenting the songs of Freed-Brown as great art deserving of an extensive cinematic showcase so much as the kind of overly caffeinated fluff that fills lesser musicals and undiscriminating vaudeville revues.

In other words, they’re the kind of tacky tunes that fill the hardscrabble early career of our heroes Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) and Cosmo Brown (Donald O’Connor) as they learn their art and craft the hard way entertaining disinterested drunks for small change until they’re kicked out of bars for being kids.

The hard-luck duo’s career continues along those lines until they end up in Hollywood during the untamed, Wild West silent era, where the cost of entry for movie stardom was so low that becoming a movie actor often seemed to be a matter of being in the right place at the right time and knowing how to take a punch or fall off a horse.

That’s how Lockwood rises from lowly extra to dashing stuntman to top matinee idol alongside Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen), a narcissistic egomaniac with an abrasive honk of a voice that makes her perfect for silent film and a nightmare for talkies.

Unfortunately for Lina and everyone forced to put up with her moods and megalomania for professional reasons the blockbuster team of Lockwood and Lamont is about to run smack dab into a brick wall called sound after a gimmicky show-business melodrama about Jewish assimilation called The Jazz Singer heralds the death of silent film and the emergence of an exhilarating and terrifying new entity that promises to change the art form dramatically.

This spells possible doom for a money-making cinematic partnership Lockwood feels ambivalently about at best and opportunity for fresh faced ingenue Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds), a gifted young performer who initially masquerades as a highbrow enthusiast of the proper theater before revealing herself to be, like Lockwood and sidekick Cosmo, a true vulgarian.

Kathy, played by a nineteen year old Reynolds in a star-making turn, may put on a big front, but she’s every bit the vaudevillian Lockwood and Cosmo are. That’s their bond: they’re razzle-dazzle entertainers supremely skilled in the All-American art of putting on a show, not sophisticated so and sos.

Kelly and O’Connor have such amazing chemistry that you’d think they were the vaudevillian team they’re playing rather than first-time collaborators who apparently did not get along terribly well due to Kelly’s demanding ways as a co-auteur. Kelly and O’Connor move as if they have helium in their veins instead of blood, as if they are one being occupying two bodies.

Singing in the Rain is fundamentally about partnerships, onscreen and off. There’s the directorial and choreography team of Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, who give the film a hard-driving sense of rhythm and a relentless, machine-gun pace that feels partially attributable to their background in dance and choreography. As Bob Fosse illustrated during his brief but important stint as a filmmaker, dancers have a sense of rhythm unlike anyone else. The editing and particularly the zippy, parodic montages here have the pounding rhythm of the Speed and amphetamine that pushed countless chorus dancers to the breaking point and beyond during the early days of sound.

Then there’s the songwriting team of Freed and Brown, who could not have asked for (or, in Freed’s case, personally helped engineer) a better vehicle for their catalog of obnoxiously, annoyingly, maddeningly infectious hits, even if the filmmakers are more interested in gleefully poking fun at the inane silliness of their fizzy, ebullient concoctions than in presenting them as overlooked masterworks.

That’s the sly duality of Singing in the Rain: it deftly, knowingly satirizes everything that makes the movies and popcorn entertainment so ridiculous while at the same time harnessing the incredible power of cheap entertainment when done correctly. Singing in the Rain has it both ways: it’s at once a love letter and a gleeful burlesque of the movie world as it made its first blundering, tentative steps into the big, scary, crazy-making world of sound film.

Singing in the Rain is as spry and light on its feet as a classic Looney Tunes short. The only element of the film that broadcasts its ambition is the “Broadway Melody” sequence. By that point the film has provided so much pure pleasure, so much sheer entertainment, that it can get away with a little art and a little ambition.

Never has a Great American movie been so in touch with its inner baggy pants vaudevillian. In tone, humor and sensibility, this is much closer to a Bugs Bunny cartoon than a Film of Importance like Gone With the Wind.

In the right hands, what O’Connor refers to as “those old honky tonk monkey shines” qualify not just as peerless entertainment but as all-time great art as well. Singing in the Rain did not aspire to historic greatness or immortality but it achieved them anyway by virtue of making audiences laugh, deeply, loudly and often but also by leaving them with a song in their heart. For various reasons, commercial, creative and otherwise, Freed and his exceedingly game, amazingly gifted collaborators wouldn’t have it any other way.

Would you like to read a massive book full of pieces like this, only shorter? Of COURSE you do! So why don’t you pre-order The Fractured Mirror, the Happy Place’s next book, a 600 page magnum opus about American films about American films, illustrated by the great Felipe Sobreiro over at https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders?

Buy The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Cynical Movie Cash-In Extended Edition at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop, signed, for just 12 dollars, shipping and handling included OR twenty seven dollars for three signed copies AND a free pack of colored pencils, shipping and taxes included

The Joy of Trash, the Happy Place’s first non-"Weird Al” Yankovic-themed book is out! And it’s only 14 dollars signed, shipping, handling and taxes included, 25 bucks for two books, domestic only! https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Buy The Joy of Trash, The Weird Accordion to Al and the The Weird Accordion to Al in both paperback and hardcover and The Weird A-Coloring to Al and The Weird A-Coloring to Al: Colored-In Special Edition signed from me personally (recommended) over at https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop

Or you can buy The Joy of Trash here and The Weird A-Coloring to Al here and The Weird Accordion to Al here

Help ensure a future for the Happy Place during an uncertain era AND get sweet merch by pledging to the site’s Patreon account at https://www.patreon.com/nathanrabinshappyplace We just added a bunch of new tiers and merchandise AND a second daily blog just for patrons!

Alternately you can buy The Weird Accordion to Al, signed, for just 19.50, tax and shipping included, at the https://www.nathanrabin.com/shop or for more, unsigned, from Amazon here.

I make my living exclusively through book sales and Patreon so please support independent media and one man’s dream and kick in a shekel or two!