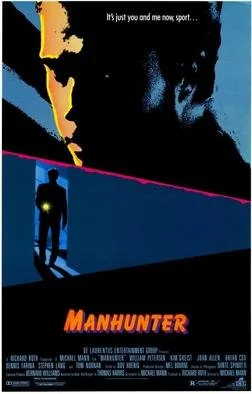

Before Silence of the Lambs, Michael Mann Brought Donald Trump's Favorite Cannibal to the Big Screen with the Mesmerizing 1986 Masterpiece Manhunter

Welcome, friends, to the latest entry in Control Nathan Rabin 4.0. It’s the career and site-sustaining column that gives YOU, the kindly, Christ-like, unbelievably sexy Nathan Rabin’s Happy Place patron, an opportunity to choose a movie that I must watch, and then write about, in exchange for a one-time, one hundred dollar pledge to the site’s Patreon account. The price goes down to seventy-five dollars for all subsequent choices

Sometimes I'll watch a movie that sends me to IMDb and/or Wikipedia in search of more information. That’s what I did with Manhunter, Michael Mann’s riveting adaptation of Thomas Harris’ 1981 novel.

I sometimes mix up Mann and William Friedkin for good reasons. They’re both tough Chicago Jews who worked in television as well as film and made stylish mid-1980s masterpieces starring William Petersen.

A trip to Friedkin’s Wikipedia page reminded me that he made an exquisitely off-brand cinematic debut with 1967’s inaccurately named Good Times, a movie-making themed vehicle for Sonny and, to a much lesser extent, Cher, which I watched and wrote up for The Fractured Mirror but got lost somewhere in the many drafts and revisions. I happily put it back in. It’s also a candidate for my 100 Worst American Movies list because it's abysmal, noteworthy for multiple reasons, and not particularly well-known, even among pop culture buffs and bad movie geeks.

Researching Manhunter, I also stumbled upon a factoid so far-fetched that it seemingly can’t be true.

When Mann was looking for someone to play Hannibal Lecktor (which is how it’s spelt here but nowhere else, maddeningly), he considered John Lithgow, Brian Dennehy, Bruce Dern, and Mandy Patinkin. He also apparently contemplated casting William Friedkin in the role despite the provocative filmmaker not being an actor.

Friedkin was a famously intense man who made movies that reflected his uncompromising aesthetic. Mann apparently thought that might work for the role.

Dennehy wanted to play the mad doctor, but made the mistake of suggesting that Mann check out a Scottish theater actor named Brian Cox.

Cox became the first person to play Hannibal Lecter (which is how I will refer to the character from here on out, for my sanity and yours) onscreen, though the film inexplicably and frustratingly spells the cinematic icon’s name differently (Lecktor) than every other book, television show, or movie.

Donald Trump has ruined many things. He ruined our country. He ruined the political process. He destroyed the Republican Party. He’s torn our country apart. He has done irreparable damage to our country it will take decades to undo.

And Donald Trump ruined Hannibal Lecter by continually referring to “the late, great Hannibal Lecter” in his speeches.

Because Donald Trump is very stupid—a dead giveaway is that he’s constantly talking about how smart he is and how dumb his enemies are, rather than illustrating his intelligence through actions and words—he probably confuses the idea of seeking asylum with insane asylums.

Trump mixes up foreigners seeking protection from their home countries with a madman in an insane asylum. Trump’s bizarre fixation with a fictional killer wouldn’t even crack a list of the 1000 most embarrassing things he’s said and done.

David Lynch was offered a chance to direct, but either turned it down flat due to his bad experience on Dune or left early in the development process.

As a thought experiment, it’s interesting to imagine what Lynch’s take on the film would have been, but it would be difficult, if not impossible, to best the work Mann does here.

Manhunter is a goddamn masterpiece. Mann is an auteur. He was the perfect director to bring Harris’ erudite, people-eating evil genius to the screen.

Mann’s third film added psychological depth to the MTV aesthetic he developed as a producer on Miami Vice.

The studio apparently wanted Mann to re-team with Don Johnson for the lead role of brilliant, obsessive FBI profiler Will Graham. Mann did not. Jeff Bridges was also considered. Bridges is probably the best actor of his generation, but Petersen does a hell of a job in a demanding role.

Manhunter served as a bridge between television and film for Mann and William Petersen, the Chicago theater actor who went on to play the role a year after headlining Friedkin’s To Live and Die in LA.

Petersen ended up making a shit-ton of money as the star of CSI, a procedural that owes a sizable debt to Manhunter. Mann’s movie focused monomaniacally on the tortured psyche of an FBI profiler, a theme that would later become a cop show cliché.

Manhunter audaciously begins seemingly somewhere in the middle, with Will Graham talking to his boss and old friend Jack Crawford (Dennis Farina, whose background as an actual detective lends authenticity to his performance) about gruesome crimes.

For the sake of his fragile psyche and marriage, our hero has stepped away from an intense, traumatizing role getting deep inside the minds of criminals after nearly getting murdered by Hannibal Lecter.

Jack knows exactly how to manipulate Will. He shows him photographs of two families that were slaughtered by an unknown maniac. He guesses correctly that he’ll look at the pictures and see his own family and the families the killer will murder next.

Will seeks help from a likely and unlikely source in the man who almost killed him. He visits the very bad doctor in his prison cell.

Mann apparently had to fight the urge to focus more heavily on Hannibal Lecter. He’s such a great character and an instant fan favorite that he knew audiences wanted more, but he didn’t want Manhunter to become a Hannibal Lecter movie instead of a movie about Will Graham where Hannibal plays a crucial but unmistakably supporting role.

The auteur made the right choice for the film, but it should be noted that when Jonathan Demme let Anthony Hopkins dominate Silence of the Lambs, the result swept the Academy Awards and was the 4th top-grossing film of 1991, after T2: Judgment Day, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, and Beauty and the Beast.

Manhunter got mixed reviews and flopped at the box office, but time has been kind to it. I see the smash hit Oscar winner and the flop in similarly high regard, as two early masterpieces that transformed Harris’ pulpy bestsellers into high art.

Cox audaciously underplays the role. Because he has so little screentime, every moment counts. Every second matters.

Hannibal immediately launches into a head game with his adversary. There’s a great exchange where Hannibal asks Will if he thinks he’s smarter than him. He also asks why he was able to catch him.

Our hard-driving hero replies dryly that he doesn’t think he’s smarter than his tormentor but that he has certain disadvantages. When he asks what kind of disadvantages, he deadpans, “You’re insane.”

Cox’s reaction is perfect. He’s an evil genius who kills and eats people. “Insane” is an understatement.

At the end of the scene, as Will storms out in an attempt to avoid being mind-fucked further by the sadist, Hannibal yells that the reason Will was able to catch him despite not being in his league intellectually is because they’re fundamentally the same.

With the possible exception of using a chess game to illustrate that characters are engaged in a metaphorical chess match, this may be the most ubiquitous and exhausted cliché in thrillers.

If executed artfully enough, every cliche can work. Mann makes this hackneyed convention sing. It helps that Mann has a skillful way with exposition.

There’s a great scene later in the movie where Will is talking to his son in a supermarket. It’s a perverse and inspired setting for one of the heaviest scenes in a movie that’s pretty much only heavy scenes.

In it, Will explains that he barely survived his run-in with Hannibal, how the psychologist got under his skin and penetrated his psyche in a way that he’s still recovering from. He tells his son that he spent time in a mental hospital because he was traumatized by what happened.

He does not sugarcoat the ugliness of his experiences. He doesn’t talk down to him. He doesn’t talk to him like a child. He gives it to him straight because he has faith that his son is capable of handling it.

I’ve seen Manhunter four or five times now. It's one of those infinitely re-watchable movies where you pick up something new each time.

I didn’t remember that Tom Noonan’s Francis Dollarhyde/Tooth Fairy/Red Dragon doesn’t appear until nearly an hour in. I also didn’t recall that we’re introduced to him in Red Dragon serial killer mode.

We see the monster, and then we see the man. In a factoid that could very well come from my Random Roles with him for The A.V. Club, apparently Noonan came into the audition and said that he wanted to just audition without making small talk or bothering with pleasantries, and Mann instantly realized that he had the off-putting weirdo creep that he was looking for.

Noonan is mesmerizing as a towering mountain of a man who cannot keep his murderous insanity from bubbling to the surface for long.

There is a fascinating contrast between Noonan’s massive frame, which makes it easy to believe he could throw grown men around like rag dolls, and the creepy gentleness of his voice and manner.

I remembered Dollarhyde being far more sympathetic than he actually is. He’s a murderous maniac who can only hide his evil insanity from someone who is literally blind.

The blind woman in question is Reba McClane. Reba was played by Joan Allen, a fellow veteran of the Chicago theater scene with only a single film role to her credit.

Allen makes such an indelible impression that she seems to have a far bigger role than she actually does. Reba alone sees the humanity and vulnerability in a monster born of trauma and pain.

Cox lends Hannibal a bone-dry sense of humor. Manhunter’s blistering intensity is offset by raucous humor in the form of Freddy Lounds (Stephen Lang), a hilarious caricature of a bottom-feeding tabloid opportunist. Philip Seymour Hoffman played him in Red Dragon. That was the only time a Red Dragon cast member matched or topped their Manhunter counterpart, though a pre-jacked Lang is exquisitely sleazy and has one of the great exits in film history, hurtling to doom in a flaming wheelchair.

In an attempt to coax Dollarhyde out of hiding, the FBI convinces Freddy’s rag to run a fake article depicting the Tooth Fairy killer as gay, impotent with women, and involved in an incestuous sexual relationship with his mother.

They know that this portrayal will enrage their prey to the point that he will lash out in vengeance. Poor Freddy ends up paying the ultimate cost for their cynical ruse, which, to an extent, works, but not in the manner intended.

Manhunter climaxes with an instant classic set-piece set to Iron Butterfly’s “In a Gadda Da Vida” that ranks as one of the most inspired uses of pop music in film history.

The 1986 cult classic seemingly set the bar impossibly high for Harris adaptations, but Demme arguably cleared it when Silence of the Lambs garnered the rave reviews, awards, and boffo box office that Manhunter deserved.

The same cannot be said of Bret Ratner’s Red Dragon, which I’ll be writing about next month, and can only suffer by comparison.

Ratner did a mediocre, half-assed job with Red Dragon. He also accidentally burned down Robert Evans’ screening room while he was staying there.

That, however, is a tale for another time, or maybe never!

You can pre-order The Fractured Mirror here: https://the-fractured-mirror.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

Nathan needed expensive, life-saving dental implants, and his dental plan didn’t cover them, so he started a GoFundMe at https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-nathans-journey-to-dental-implants. Give if you can!

Did you enjoy this article? Then consider becoming a patron here.